In this first part, I will give a short introduction to the

history of North Korea’s nuclear program and then discuss the health risks

found within the uranium mining and milling process and the production of

nuclear fuel. (Read Part II here)

Image source: Sakucae/2.0

Introduction

North Korea can trace its nuclear program to soon after the

Korean War. After the war’s total devastation, Kim Il Sung vowed that the

country would never again be flattened, and he sought Soviet assistance in

creating Pyongyang’s own nuclear deterrent. Marshall Stalin and future Soviet

leaders weren’t too keen on Kim’s aspirations initially, but they did offer

help with the development of nuclear power and signed a nuclear cooperation

agreement in 1959. Never one to let an opportunity go to waste, Kim Il Sung

ordered secret research into building the A-bomb.

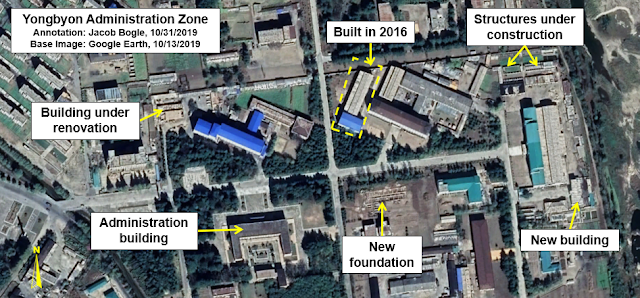

Yongbyon, North Korea’s main nuclear research center, was

constructed in the 1960s with help from the Soviet Union. Further facilities

across the country were constructed that were needed to mine the uranium, mill

it, and finally, to enrich it. The country has two known milling facilities,

one at at Pakchon and Pyongsan, and around dozen suspected uranium mining

sites. Pakchon and Pyongsan process low-grade coal to concentrate the uranium

naturally found within it (at relatively low concentrations)

and then to turn it into yellowcake where the uranium concentration reaches

80%. From there it is sent to additional facilities including Yongbyon, some of

which have likely not been declared by North Korea to the international

community.

Mining and milling

North Korea is one of only seven countries that are not

signatories to the International Labor Organization. This United Nations agency

sets international labor standards, including those for nuclear research and

industry. Furthermore, the country’s mining sector is notoriously dangerous and

lacks modern safety precautions and necessary equipment. Injuries and

respiratory diseases are common, particularly in coal mines which is where

North Korea gets the bulk of its uranium. The country’s two largest uranium

mines, Pyongsan and Woogi-ri (within the Undok-Rason area), hold an estimated 11.5

million tonnes of ore and employ thousands of workers.

The inhuman treatment of workers at Pyongsan, and severe

negligence regarding monitoring radiation exposure and air quality was given in

testimony

by Dr. Shin Chang-hoon before the U.S House in 2014.

Once the ore leaves the mines, it is transported to the milling plants to be converted into yellowcake. Even though coal itself is generally considered safe to handle, every form of uranium extraction leaves behind dangerous waste.

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency,

"regardless

of how uranium is extracted from rock, the processes leave behind radioactive

waste....The tailings remain radioactive and contain hazardous chemicals from

the recovery process."

The Pyongsan milling plant is a prime example of the

environmental damage done within North Korea’s nuclear sector. Satellite

imagery shows that the country’s primary milling facility has been spilling

industrial waste into the Ryesong River for decades, and that the waste

material reservoir is unlined. This can allow contaminated water to seep into

groundwater supplies and also contaminate crops. Hundreds of thousands live

within the area of Pyongsan and downriver of the plant.

Non-proliferation expert Dr. Jeffrey Lewis summed it up

nicely in 2015 when he said,

“What is definitely happening, though, is that North Korea is dumping the

tailings from the plant into an unlined pond, one surrounded by farms. That’s

not a hypothetical harm. That’s actual pollution that is harming the

health and well being of the local community."

At Pakchon, which began uranium milling around 1982, a former waste reservoir is now covered in cultivated land. This practice can be seen at many mining and industrial sites. If the waste isn’t properly covered, any crops grown over this material may become contaminated with heavy metals such as vanadium and chromium, as well as lead and arsenic. Those contaminates are passed up the food-chain into animals and humans.

According to defector Kim Tae-ho, who worked at Pakchon in the 1990s, when the “experimental plant” would operate, yellow smoke would fill the plant and cause “severe difficult breathing and unbearable pain.” The short-term effect of inhaling yellowcake particles is primarily kidney damage which will resolve itself unless there is recurrent exposure (such as from working at the site each day). However, the main radiological risk comes from the radioactive gas radon and its non-gaseous “daughters” like polonium-218. Improperly vented air can lead to a build up of these radioactive materials and will cause immediate tissue damage to the lungs and mucus membranes. Additionally, the use of acids in the production process raises the risk for inhalation of sulfur-containing gases (which can have a yellow tint to them) and cause irritation and eventually burns to the eyes and lungs.

Pakchon and Pyongsan are combined mine and milling

facilities, but illnesses and food contamination have been reported at stand-alone

mines as well, such as at the Walbisan uranium mine (near Sunchon).

Sources told Radio Free Asia that, “local residents are forced to eat radioactive food and drink radioactive water,” and “[i]n Tongam village, the miners and their families suffer from incurable diseases or various types of cancer. In particular, many people die of liver cancer.”

Sources told Radio Free Asia that, “local residents are forced to eat radioactive food and drink radioactive water,” and “[i]n Tongam village, the miners and their families suffer from incurable diseases or various types of cancer. In particular, many people die of liver cancer.”

Enrichment and fuel production

Even within the uranium enrichment compound, almost every inch of available land has been cultivated.

The next steps along the nuclear development chain happen at

Yongbyon. The complex exists as a closed-city and people are not free to enter

or exit without permission. Scientists, engineers, and others may work for many

years within the fenced off complex. They will marry and will raise children.

While being able to work within a prominent field brings

many benefits, it also brings risks. Brief exposure to radiation is rarely

dangerous. Short exposure risks are also not catastrophic when it comes to

inheritable genetic damage, either, as the world learned from the survivors of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But continual exposure because you’re living in a

contaminated environment increases those risks each day. This concern grows

when you consider that in recent years, dozens of new buildings have been

constructed with room for thousands more residents.

Scientists who were involved during the early days of

Yongbyon’s operation have been reported to

have suffered from wasting illnesses and hair loss.

"In other

districts it is very difficult to find people with cleft lip but here there are

many individuals with crooked mouths, those lacking eyebrows, incidents of

dwarfism, and those with six fingers. There are even children who just look

like bare bones."

Adults can also be affected, with the most severe cases eventually causing mental deficiencies, cancers, and wide array of other illnesses at relatively young ages.

The aforementioned Dr. Shin Chang-hoon also interviewed a defector who worked at Yongbyon. He was told that the dosimeters (which measure radiation exposure) were only checked every three months and workers were not told of the results unless they had already begun to exhibit signs of radiation sickness.

Adjacent to an area of improperly stored nuclear waste is a grove of dying trees and farmland. It is only separated from the waste by a covering of dirt.

Improper disposal of radioactive materials can pollute the

soil, kill trees, and contaminate any food that is grown in the area. Releases

of gases into the atmosphere will likewise blanket the region and small,

aerosolized particles will eventually make their way down to the ground,

bringing with them radiation or forming toxic compounds. These gases can travel

for many miles and place other sites within North Korea at greater risk, not

just the immediate Yongbyon complex.

Concern over Yongbyon is especially grave considering the

large number of nuclear and chemical facilities in such a small area. Not just

in terms of ongoing dangers that defectors have told the world about, but also

in terms of a future accident, flood, or fire that could devastate the region

and require international intervention to solve.

The fact North Korea is largely cut off from the world and often must rely on outdated science, manufacturing techniques, and potentially unreliable indigenously produced parts and equipment means that the risk of accidents and errors is greater than in other nuclear countries. It is something of a small miracle that a large-scale incident hasn’t already occurred.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters: Kbechs87, GreatPoppo, and Planefag.

--Jacob Bogle, 12/22/2019

Patreon.com/accessdprk

JacobBogle.com

Facebook.com/accessdprk

Twitter.com/JacobBogle