This is a breakdown of North Korea by the numbers based on the AccessDPRK 2021 Map, Pro Version. This is similar to the North Korea by the Numbers post I made for the 2017 map.

Since I want to give a full accounting of all of the different places that are in the country, I am basing this off of the Pro map, which has thousands more places than the free version.

My interest in North Korea began in late 2012, then I found some older maps others had done and decided to make a truly comprehensive version, as all of the others were either severely lacking or only focused on one sector (like Planman's great work on air defense sites). I started the blog in 2013 and released an early version of the work in 2016. Then came the first "full" map in 2017 and finally the 2021 map, which will be the last comprehensive nationwide map of the country I plan to make.

As all of my maps have been divided into monuments, military, and domestic sites, I'll give their overall numbers first.

The project has located 11,661 extant monuments in North Korea. There's 13,566 military sites (manned, unmanned, and former). And there's 39,407 domestic sites marked. This represents a 18.1% increase from the 2017 map; however, the military folder is actually over 41% larger than the 2017 military folder. That's 64,634 sites.

The provincial breakdown for the monuments is:

The military folder of the 2021 Pro Map is over 41% larger than the 2017 military folder. This isn't because I missed a bunch of places, but it's due to the fact that I wanted to give an even more granular look at the country's military, trends, and changes over time. This means I focused on mapping even former facilities, located the storage sites within military bases, paid special attention to locating tunnels and underground sites that may have been well hidden, and marked important bases (like missile sites) with greater detail. The change is also due to improvements in available imagery, making it possible to discover things that were previously too blurry to be identifiable.

A few of the specific improved numbers are: 110 additional observation posts along the DMZ (at least 18 were built after 2015), 44 additional radar facilities, 67 more AAA sites (15 were built from 2015-2019), and over 400 additional verified military bases. Then there's the 126 hardened artillery sites that have been constructed since 2010. However, one of the largest increases comes from the storage facilities (stand-alone and within other bases) that I gave more attention to for 2021. The map includes 1,337 of them. That's a further 650 sites compared to 2017.

Since I have also tried to locate former artillery sites (so that other maps can be updated) and additional decommissioned bases to help researchers understand military infrastructure trends, I think it's important to say that of the 13,566 military-related sites, only about 900 (or 6.6%) are not part of the country's active defense. That means there's roughly 12,666 currently used sites (everything from missile bases to static, anti-invasion road blocks to tunnel groups and DMZ posts).

A notable change between 2017 and 2021 is the fact that there are 314 fewer propaganda signs marked. This is because many of them are simple wooden signs or chalk outlines on hillsides. Over time they fall down or are washed away.

The demolition or other removal of sites, plus the fact that I did not include two 2017 categories (mountain peaks and Pyongyang bridges), means that the gross difference between the two maps is actually closer to 21-22%, and that the 2021 Pro map has ~11,600 entirely new places vs. 2017.

Some other changes worth noting is that there are 320 additional dams and hydroelectric sites marked, 71 additional markets, 371 more border posts (reflecting Kim Jong Un's efforts over the years to end defections), and there's the places that can only be found in the Pro Version. These include 149 gas stations (a growing trend in the country), the locations of 320 likely Railway Security Bureau facilities, and a national map of the country's lighthouses (some of which were only built in recent years).

Notes:

I want to add a few notes to help with context and prevent any confusion.

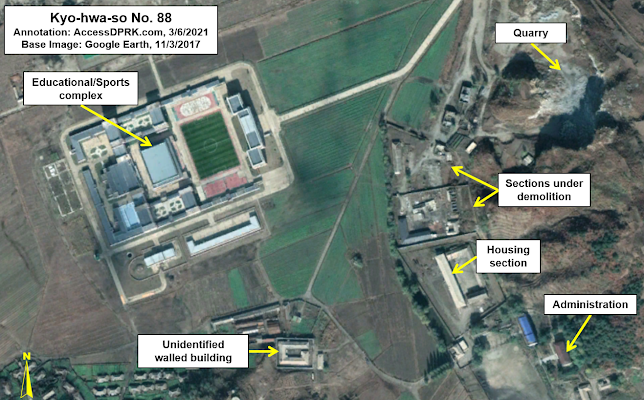

While most of the categories are indeed individual sites (there are 1,485 distinct electrical substations for example), some of the categories include not just the primary location but also sites within those places. A great example of this is that there are not 412 prisons in the country. There's 53 known, suspected, and former prisons that I was able to locate. And many of those prisons include detailed maps that also mark where the guard huts are, where prisoner housing is, and so on. So, one prison may be represented by 20+ items, and that's how I get to 412 total sites within the prison category.

The categories that have these more detailed folders are: prisons, missile bases, some historic sites, several of the "elite compounds", and a few factories. Additionally, some of the "province only sites" include multiple sites per place. This is especially true in Pyongyang which has the most of these province-only sites. An example is the Ryongsong Residence, which located within the "province only" folder, but that one residence includes 47 detailed sites within its folder. So, while there are 681 markers within the whole "province only" category, they're only representing around 275 primary places as several of those primary places have numerous sites marked within.

Lastly, in some cases I did not try to map every single one of the sites within a category. There are notes in the respective folders saying this, but they are: irrigation pumping stations, water supply, factories, agricultural sites, internal security checkpoints, parks, and gates. I tried to map a majority of sites and all of the important ones with the exception of the water supply sites, agricultural sites, internal checkpoints, and gates. For those, I wanted to give a representative sample and to locate major places. I only marked gates in cases where a facility was large and the main entrance could be difficult to find, and in cases where the gate itself was interesting/large.

--Jacob Bogle, 3/27/2021