Kim Jong-un with

his wife, leading DPRK officials up Mt. Paektu in 2019. Image source: KCNA.

Introduction

Throughout this series, I have tried to draw from numerous

sources to provide an accurate accounting of the first decade of Kim Jong-un’s

rule and to limit the number of my own opinion-based comments. For this final

article, opinion is about all that anyone could offer. Informed opinion, but

opinion and supposition, nonetheless.

People have offered predictions about North Korea since its

inception. That there was no way it could survive the Korean War. That Kim

Il-sung would end the nuclear program. That Kim Jong-il would falter in the

face of famine and the whole system would collapse. That Kim Jong-un couldn’t

handle power at such a young age or that war is inevitable.

Those predictions were all wrong. At the same time, plenty

of other predictions have been right. That the government would survive the

famine because it didn’t care about cutting less desirable citizens off from

food. That the country would achieve nuclear miniaturization. That it wouldn’t

stop illicit trade activities regardless of the United Nations and especially

regardless of the United States.

So, this ‘look to the future’ opinion piece is just as

likely to be wrong and to be right and to have areas of grey as the future

unfolds and becomes the present. With that caveat, I will attempt to look at

the trends of the last decade, the changes, and what’s stayed the same from Kim

to Kim to Kim to inform my own views of what the next decade of Kim Jong-un’s

rule may look like.

COVID and the Economy

The most pressing issue that Kim Jong-un will have to

resolve is that of economic contraction due to his lockdown of the country over

COVID-19 fears. After two years of very limited trade and internal quarantine

measures, the economy is suffering more than it has at any other point during

his rule and the food situation, in particular, has reached a critical point.

Although illicit activities have continued unabated,

bringing in hundreds

of millions each year, there is little indication that those funds are

being used to prop up the economy; rather, they are most likely being used to

maintain Kim’s lifestyle, provide gifts to the elites to keep their loyalty,

and to continue the country’s military buildup.

As such, legal trade must resume before a crisis becomes inescapable, leading to future disease outbreaks (such as from

tuberculosis), a limited famine, or even popular unrest. Kim will also have to

consider finally allowing vaccines into the country as COVID-19 stops being a

pandemic and transitions to an endemic global illness that will be around for

years.

Leaving no opportunity behind, the COVID lockdown actually provides Kim the opportunity to

gain greater control over the broader economy and over the economic activities of the

people as the ‘border blockade’ has made it even more difficult for unapproved

cross-border trading to continue. This places the state in a better position to

control and monitor what goods come into the country, and it has set up at

least two decontamination centers to help facilitate the resumption of trade:

one in Sinuiju and one at the Port of Nampo.

A test

run at the Sinuiju center recently took place on January 17, 2022, when a

train entered North Korea from China after a two-year border shutdown resulted

in an 80% drop in trade with the country. The outcome of the train visit and

how well the government thinks the Sinuiju facility handled the operation may

allow for a slow resumption of trade in the near future.

One twist in North Korea’s economic story has been how Kim,

in the early years, allowed limited reform and the markets to continue to grow,

but under COVID he has reverted back to more anti-market policies,

desperately trying to reign in free market activities and strengthen the

state’s central control over the economy. How this struggle against

marketization will play out is anyone’s guess, but one complication that Kim is

currently having to deal with and will continue to need to contain in future

years is the “tyranny of growing

expectations”.

As people

become accustomed to a certain living standard, they begin to expect more from

their government and begin to expect that life in the future will be better

than what they have today. In a growing globalized world, this works itself out

through expanding free markets and liberalized governments. But in North Korea

and other closed states in the past, it can turn into a major threat to the

regime as the government cannot compete with the gains made by

marketization, and as the people realize that the outside world is much

wealthier and freer than what they have at home.

Kim Jong-un

made improving living standards and access to consumer goods a key pillar of

his rule since the beginning. Promising no more ‘belt tightening’ in 2012, the

government is today telling people that they should expect food shortages until

at least 2025. After the moderate but measurable rise in living standards of

the last 10-15 years, if the government isn’t able to maintain upward growth,

then the popular pressure of growing expectations can serve to destabilize the

regime.

Should this

meld with other pressures against the current system, an inescapable domino

effect may occur in the future, leading to the end of the state. This has been

one of the biggest threats to the Kim’s and it is something they have managed

to avoid thus far, but no one knows where the ultimate tipping point lies.

Regardless of

economic reforms or further ossification, one thing, of course, that continued

throughout the pandemic and will continue well into the future is North

Korea’s illicit activities. Whether it’s selling counterfeit goods, money

laundering and theft, or busting sanctions with oil, fish, luxury goods, and

other commodities, the state will keep relying on these ill-gotten millions

each year to try to stabilize the system and keep the elites in lockstep with

Kim Jong-un.

Weapon Development

Missile development is the next most important

issue as Kim Jong-un works toward realizing his “wish list” as laid out in his

speech to the 8th WPK Congress in January 2021. This list includes everything from developing improved ICBMs to hypersonic glide vehicles to

tactical nuclear bombs and other weapon systems.

Kim Jong-un spent much of 2021 testing multiple weapons and

showed off a wide range of equipment (some known, some new) during the “Self

Defense 2021” exhibition. He also began 2022 with a series of seven missile

launches that included its longest-range missile test since 2017.

Since the failed summits, North Korea has embarked on a

series of technology demonstrators like the hypersonic glide vehicles (showing

off two different designs) and rail-based missile launches. Having declared the

country’s nuclear deterrent complete, Kim is going to need to continually

develop new delivery methods and to improve his nuclear arsenal’s

survivability, as it currently relies on a limited number of large, slow-moving

TELs that cannot be easily replaced. This helps to explain the proliferation of

weapon designs as well as radar and improved air defense systems.

I believe that future nuclear tests are unlikely, but they can’t be ruled out as Punggye-ri still has two functional tunnels. And after North Korea implied that the self-imposed moratorium on testing would no longer be adhered to, it does place future tests on the table.

In terms of sanctions, I think that it is unarguable that they

have been an abject failure. Upwards of two hundred thousand citizens are still

locked in prison camps, the country has tested nuclear weapons and created

miniaturized warheads, North Korea has missiles that can reach the United

States, and the Kim family is still firmly in control. However, one reason why

sanctions have failed is that the enforcement of those international

sanctions is rooted in each individual UN member state’s own interpretations of

the sanctions and their own willingness to enforce them.

China has been integral to North Korea’s ability to skirt

sanctions and carry out illegal activities. And while China occasionally gets

tired of Pyongyang’s behavior and temporarily gets stricter with enforcement,

the existence of North Korea is within their own national self-interest. This

means that China will never do anything that might directly cause the collapse

of the current government short of North Korea declaring war or causing

significant damage to China itself.

Therefore, absent greater international pressure on China to

plug the enforcement leaks and loopholes, China will continue to be North

Korea’s lifeline and Kim Jong-un will continue using this to his advantage.

Until China becomes willing to strictly enforce sanctions or

until either the United States or South Korea becomes willing to cave on major

issues (all unlikely scenarios), North Korea is going to keep testing

weapons. The goal of complete, verifiable, and irreversible denuclearization

(CVID) is now completely unrealistic unless the United States is willing to go to

war, which it hasn’t been despite the murder of multiple US military personnel

and the assassination of multiple South Korean officials over the decades.

In my view, the only viable option is that of arms control,

limiting the number of warheads and their yields, limiting the range of

missiles, and limiting the numbers of launchers North Korea can have in

exchange for substantial sanctions relief.

However, the human rights situation complicates matters as does

Pyongyang’s history of ignoring agreements.

At least in the near term, we should certainly engage in

talks but the longer-term position is likely to

be merely “wait and see,” as neither side seems willing or capable of making the

difficult decisions or want to risk losing face, and as North Korea hasn’t been

patient enough for slower confidence-building measures prior to more

substantial agreements.

Human Rights

Domestically, human rights abuses will assuredly continue. Kim Jong-un has shown little inclination to degrade the state’s

system of prison camps and he has ramped up internal surveillance to levels not

seen since Kim Il-sung.

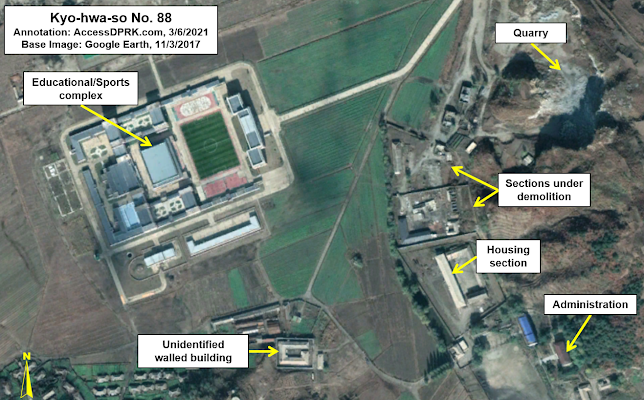

Although Camp 22 was closed under his watch in 2012, many of

the prisoners were merely transferred to other sites, and others are alleged to

have been allowed to starve to death to enable the camp’s closure.

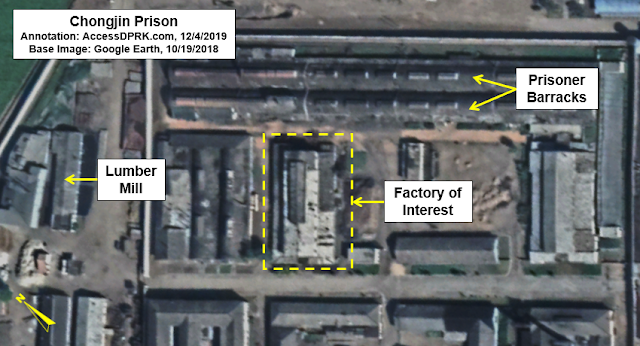

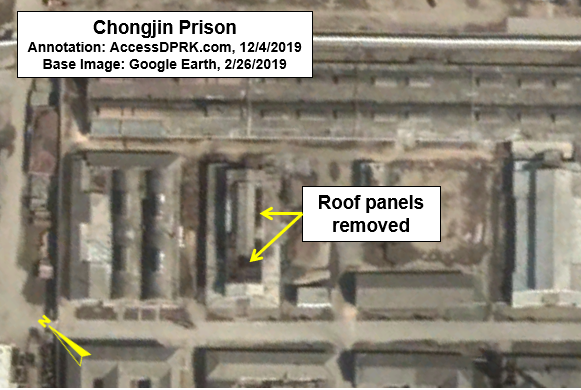

In contrast, prisons in Pokchong-ni, Kangdong, Chidong-ri,

Yongdam, Nongpo, Chongjin, Hwasong, Pukchang, and others have all seen new

construction or renovations to their facilities. Additionally, public

executions outside of the prisons, within regular towns and villages, have

reportedly not ended and are now carried out for things like watching certain foreign media.

Since coming to power, Kim Jong-un has directed the Ministry

of Social Security, Ministry of State Security, the People’s Border Guards, and

other relevant agencies to crackdown on defections and unapproved cross-border

economic activity. In 2011, 2,706 defectors made it to South Korea. By 2018,

only 1,137 defectors were able to make it to the South. However, COVID-19 gave

Kim a great opportunity to ramp up the repression of freedom of movement.

Hundreds of new border guard huts and hundreds of kilometers

of new border fencing have been erected during the pandemic. While

anti-defection measures had been begun prior to COVID, nearly the entire

northern border ended up with a double row of electrified fencing since the

beginning of the pandemic. Although the ‘border blockade’ is ostensibly to prevent the

spread of the virus from Chinese persons and goods illegally crossing the

border, it has served to nearly end defections.

In 2021 a mere 63

defectors made it to South Korea.

Freedom of expression and thought have also come under

greater assault, especially in the last few years, as Kim has solidified his

rule and now looks forward to being the only Kim in charge for another

generation or two, in the model of his grandfather.

There is no greater threat to a closed society than

information and no greater threat to an authoritarian system than

individuality. It is said that blue

jeans helped bring down communism. This wasn’t because jeans come with guns

or brings down economies, but because they became a symbol of capitalism and

individuality. While the saying is overly simplistic, that basic article of

clothing became subversive and was a reminder that the free world and its

values were thriving, while breadlines and secret police were all communism had

to offer.

Similarly, North Korea has relied upon the group subsuming

the individual. The masses, as a unified whole, are what the North Korean government

and society are built upon. The individual only exists as an entity for so long

as they give themselves over the larger group and never turn their back on

socialism by highlighting their individuality or demanding to be treated as a human being equal to any other.

This feature of all authoritarian regimes, left and right,

is relied on to keep the masses in line and curtail any risk of nonconforming

thoughts and actions. It is this feature that Kim Il-sung wielded to such a

great effect that for a stretch of thirty years, almost no known public demonstrations or other

protests occurred.

And after the breakdown of the information cordon in the

1990s, it is this feature that Kim Jong-un must learn to wield again, or else he

will have to accept that permanent cracks in the system exist and may one day

bring the entire system crashing down.

To this end, more and more effort is being expended on

hunting down purveyors of smuggled media material, cell phone tracking and

blocking technology has been installed along the entire Sino-DPRK border, and the

government has taken greater

steps to punish officials and police who turn a blind eye toward or take

bribes to overlook illegal activity. Even

attacks on everything from non-traditional hairstyles to using foreign slang

have been couched in terms of national salvation – of restoring a true

socialist community by going after impure, reactionary elements.

Kim Jong-un has even leveraged South Korea’s desires for

diplomatic normalization to get the South Korean government to pass laws violating

human rights within the ROK merely to appease him. But all that has done is

hurt the South’s own legitimacy and standing as a democratic beacon in the

region while enabling Kim Jong-un to limit the flow of outside information and

culture into the country.

In my view, it’s hard to see a time when this rise in human

rights abuses will end so long as the invisible yet existential threat of COVID

exists. Of course, the government has never needed a real threat to its

existence to lash out at foreign elements within the self-proclaimed racially

and culturally pure North Korean community, but COVID happens to be a very real

threat and provides an excellent opportunity for Kim to maintain his veer

toward greater authoritarianism.

Future of Foreign Relations

Between assassinations, further missile and nuclear tests,

and a never-ending list of illicit activities, North Korea has become more and

more isolated under Kim Jong-un. The government’s anti-pandemic measures have

only exacerbated this with the removal of diplomatic and foreign aid staff from

the country. But North Korea has still tried to strengthen ties with China and

Russia, as well as Eastern European and African countries through the

exploitation of DPRK citizens as foreign labor and, occasionally, construction project

leaders.

The long and turbid history of North Korea’s interactions

with the world has created an unstable environment with little ingrained

goodwill or trust among all parties. Its history with the United States has been

particularly fraught.

The Clinton administration thought it had a workable deal in the development of the Agreed Framework, but the death of Kim Il-sung and subsequent famine

radically altered the world Kim Jong-il was forced to face, and the Bush

administration posed a much different threat in Kim Jong-il’s view after North

Korea was labeled as part of the Axis of Evil and with the eventual invasion of

Iraq. Under Obama, ‘strategic patience’ only allowed Kim Jong-il and eventually

Kim Jong-un to continue their military buildup and created no real progress on

the diplomatic front. With President Trump, ‘maximum pressure’ was about as

unserious a campaign as one could think of. Despite the horrifying bluster with

both sides threatening the annihilation of the other, maximum pressure was more

like moderate suggestions, particularly as international efforts continued to

hinge on China’s willingness (or lack thereof) to enforce the will of the

United Nations.

After a year of a new administration under Biden, it has

become obvious that the United States lacks

the bandwidth to deal with Kim Jong-un. In the face of continual missile

tests, failed summits, and mounting geopolitical problems elsewhere, Americans

and the international community itself seem to be going numb to Pyongyang.

Launches no longer draw the media attention they once did

and South Korea’s official announcements regarding activity at various nuclear

facilities have basically become exact copies of each other, with only the

dates changed.

In such an apathetic environment, it’s difficult to see how

any progress can be made. And as Russia and China continue to serve as

lifelines in the face of international will, dealing with Pyongyang can never

simply be a bilateral proposition.

Of course, the only reason anyone even cares about North

Korea is because North Korea made itself a problem. It has commanded the

world’s attention for generations through threats and belligerent actions. Receding

into the background is not the Kim way.

Kim Jong-un will eventually do something that catches the

world’s eye once again, and we can only hope that the international community

is willing to address whatever that is. Ignoring Pyongyang only emboldens the

regime. And while there may be no good options currently and although there

have been many failures over the years, discussion and diplomacy are still the

best policy – even in the absence of grand agreements or apocalyptic

threats.

Tomorrow’s Personality Cult

The half-life of the North Korean cult of personality is

roughly the reign of one Kim. During Kim Il-sung’s rule over the country, he

was a genuinely beloved and respected leader. The cult under Kim Jong-il fell

precipitously as upwards of 1 million North Koreans died under his watch, but

the state’s system of indoctrination from birth and its security apparatus

insured that the cult survived. Under Kim Jong-un, the cult has weakened

further, with many young people reportedly not caring about the great ‘Paektu

Bloodline’ or his alleged brilliance.

To counter this, Kim has taken multiple steps to shore up

the cult, and, assuming he survives another ten years, these steps can be

expected to continue as the cult forms one of the ideological pillars for the

state’s very existence and must be maintained.

During his first years, Kim tried to solidify his rule by

drawing direct comparisons between himself and Kim Il-sung. His appearance,

dress, more personable qualities, and even riding around on white horses, all

reminded the people that he was not just another leader but was the rightful

heir to Kim Il-sung.

Even his ability to complete the country’s nuclear program

and bring a United States president to cross the DMZ all underscored the

divine blood flowing in his veins. Still, younger generations have been far

more concerned with economic betterment and cultural exchanges than they have

been with ridged ideologies. And this poses a long-term threat to the

government.

Kim has taken the opportunities provided by COVID-19 to try

to reestablish a sense of national unity through a shared crisis, and in

doing so, has double-downed on the development of his own personality cult. To

do this, he has turned the sacrifice of personal liberties into an expression of true patriotism, for only the Kim family,

Juche, and the Monolithic

Ideological System can save the country.

As part of this, he has attacked foreign cultural

influences, particularly that of South Korean music and other entertainment, with

a key focus on rooting out these influences from among

the nation’s youth. A so-called “thought law” was implemented in 2021 that

goes after those using South Korean slang, efforts have been redoubled to

punish those watching foreign media, with executions in store for those accused

of distributing the material, and even personal fashion choices have been attacked as being anti-socialist and part of the corrupting influence

of capitalism.

With the information cordon that so dramatically cracked

under Kim Jong-il being reestablished and cross-border travel becoming ever

more difficult, Kim Jong-un is working toward rebuilding the ‘hermit kingdom’

of his grandfather, with as many vestiges of western influences wiped out as

possible. The end results being a population less susceptible to revolution,

greater government control over the people’s daily lives, less market activity,

and it has prolonged the longevity of the Kim family’s rule over the country.

Succession & Future of Government

With questions about Kim Jong-un’s health dogging his entire

reign, and the fact it is known that he has experienced medical emergencies,

the matter of succession is more pressing than it otherwise would be for a

ruler still in his thirties.

Kim Jong-un has made a series of structural changes to the

rules of the WPK that could, theoretically, allow for the future succession of a

non-Kim family member. He has also placed his sister, Kim Yo-jong, in positions

of moderate official power while giving her substantial practical authority.

She appears to be the most trusted person in his orbit and can routinely be

seen following behind her brother taking notes and keeping meetings/events on

track. Additionally, she has been given more leeway to voice her own views than

anyone since Kim Jong-il was still being groomed by Kim Il-sung.

Given that Kim doesn’t have any adult children, killed his

half-brother, and his other brother has largely been kept in the background,

this points to Kim Yo-jong being the de facto successor in the event of

an emergency.

Once Kim’s own children come of age, this is likely to

change but for the time being, Yo-jong can be considered to be the second most

important person in the country. While she lacks the needed official Party and

military titles to take over, what’s important is Kim Jong-un’s faith in her

and the fact that she has been able to build her own support base within the

Party and even the military.

Kim Jong-un will also continue to reform the government and

Party to fit the particular needs of his era. Loosening agricultural controls

to improve productivity, seeking greater government revenue via market

fees/taxes, the further militarization of the civilian police force, and the

ongoing shift away from the Songun Policy have all made their mark.

What’s more, is as Kim has replaced older Party apparatchiks

and military officers, he has opened up the opportunity to rearrange the inner

workings of both organizations to cut down on corruption (which drains money and

authority away from the central government), introduce and enforce his own

ideological views, and he can gradually set up frameworks to deal with major

crises of leadership such as if he became incapacitated or died, as well as to

develop a more robust command and control system regarding nuclear weapons.

Trying to understand the decision-making process and the

“why’s” within North Korea is often a form of reading tea leaves, but it is my

suspicion that the cumulative effect of Kim’s efforts on the structure of the

WPK and the military will lead to organizations that, in the end, will be

markedly more modern and forward-looking, creating a more viable system for

the future.

Final Thoughts

Contrary to predictions of the Kim regime collapsing or

that Kim Jong-un would be a Western-minded reformer, as Pratik Jakhar has noted,

his rule has been “remarkably resilient and consistent. Kim Jong Un has stayed

within the confines of the framework established by his grandfather Kim Il Sung

and inherited from his father Kim Jong Il. In the process, he has preserved

state oppression, class divisions, purges, military adventurism, economic

control and mandated glorification of the Kim family.”

Jakhar’s view sums up the last ten years and I believe it is

prescience for the next ten years as well.

Throughout this biographical series, we have seen that although

Kim has initiated a number of changes, they have been on the periphery and

still uphold the core values of the regime. Massive construction projects and

megafarms have always been part of Pyongyang’s agenda. The roots of North

Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs date to soon after the Korean

War and have melded into the national psyche, making their development an

integral part of the state’s legitimacy. And there has been no decline in

rampant human rights abuses nor has there been a move away from the personality

cult.

External forces always elicit responses and policy changes

to fit the moment, but they have followed tried and true formulas that have

kept North Korea going for 77 years. Meaningful structural changes to the way

things are done are never done in haste. What drift there has been over the

years since the early days of Kim Il-sung has largely been incremental, with

Party hagiographers and archivists taking care to erase any public trace of old

policies that are no longer supported by the current ideological flavor.

Over the next decade, Kim Jong-un will undoubtedly face new

challenges and will continue to face growing threats from within the country

such as information sharing and marketization. But if the last ten years have

taught us anything, it’s that he can be relied upon to employ terror

tactics within and without, and that he is only open to reform so long as that

reform can help ensure the state’s longevity and his premier position within

it.

And until China decides to step up its enforcement of

international sanctions, there is little reason to believe that things like missile tests, illicit trade, financial crimes, and human labor trafficking won’t continue.

~ ~ ~ ~

I have scheduled this

project to run through to the end of the year, with a new article coming

out roughly every 10 days or so. If you would like to support the project and

help me with research costs, please consider supporting AccessDPRK on Patreon. Those

supporters donating $15 or more each month will be entitled to a final PDF

version of all the articles together that will also have additional information

included once the series is finished. They will also receive a Google Earth map

related to the events in the series, and can get access to the underlying data

behind the supplemental reports.

Supporters at other levels will be sent each new article a

day before it’s published and will also receive a mention as seen below.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters: Amanda O.,

GreatPoppo, Joel Parish, John Pike, Kbechs87, and Russ Johnson.

--Jacob Bogle, 2/23/2022