Located near the city of Wonsan, in the village of Sokhyol-ri, is a small reeducation prison camp (39.158666° 127.363326°).

Reeducation camps (Kyo-hwa-so) are different from the major concentration camps (Kwa-li-so) most are aware of. These are smaller prisons that use forced labor to "correct" the thoughts of the prisoners and instill in them greater love and respect for the state. Through their labor they are remade into "good citizens". However, these prisons aren't like the ones found in America or elsewhere where prisoners make car license plates for nominal pay or a chance at an early release.

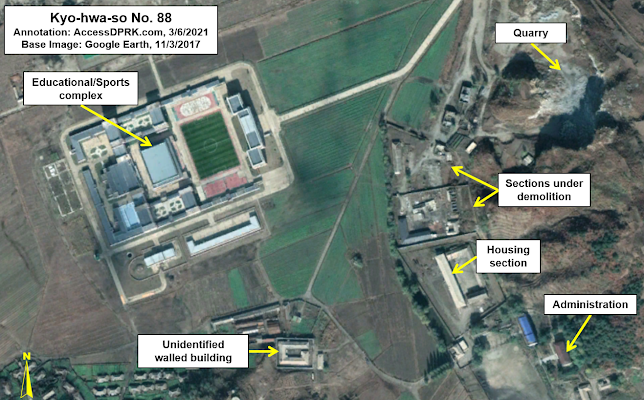

Prisoners can be required to work 18 hours a day doing hard labor and being beaten by their guards. All while being fed only a subsistence diet. There's no check waiting at the end of their sentence and they often experience lifelong disabilities. This is undoubtedly true at Sokhyol-ri (Kyo-hwa-so No. 88) because the prison provides the workforce for a nearby quarry.

The public became aware of Kyo-hwa-so No. 88 in 2011 through the Database Center for North Korea Human Rights (NKDB) publication Prisoners in North Korea. While the camp has since been mentioned by other organizations, there remains very little public information about the prison. However, a review of Landsat imagery shows that it has been in operation since at least 1985. And, unlike many smaller prisons that were closed down throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Kyo-hwa-so No. 88 was kept operational.

There are no prisoner testimonies directly from Kyo-hwa-so No. 88, but the quarrying site was identified as the prison by the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea (HRNK) in the 2017 Parallel Gulag report, as its layout fits with known prison designs in the country.

In 2012 the active quarry site was about 6,500 sq. meters in size. By 2020 it had grown substantially. The largest quarry expansion corresponds with the changes to the prison complex from 2017 and 2019. Based on its maximum size, I estimate that the prison population is between 1,000-1,500.

There is a small walled building 180 meters to the east of the main prison that was constructed in 2007. The compound encloses 2,020 sq. meters. I do not know if this is a prison annex or has another purpose.

From the above Google Earth image, one can see the layout of the prison as it was at its height. A perimeter wall surrounded part of the quarry and the workshops and housing are fully encircled by walls. The eastern part of the prison complex (the area behind the quarry) does not need any substantial security as the quarry itself provides a wall of stone, enabling that portion of the prison to be protected by a handful of guards. The explosives area has its own fence and a security hut (added in 2012), ensuring that materials aren't stolen.

In 2009, the prison and quarry complex occupied approximately 17.1 hectares.

The first major sign of change came in 2013, when the roof of the main workshop had been removed.

Currently, the prisoner housing and administration area occupies ~6.48 hectares, while the quarry size has grown by 28% since 2007.

Whether or not the prison has been fully decommissioned or merely decreased in size, with the quarry becoming a civilian site, is not confirmed. The urge to speculate is strong, but the only things that can be said for certain are what the satellite images show us. Not intentions, not the future.

However, as I've said above, such changes have happened before. It could also be the case that the regime is in the process of realigning their prison system. Unfortunately, reports of recent amnesties followed by reports that Kim Jong Un is going to be expanding the prison system doesn't give us a clear answer.

It is just as likely that Kyo-hwa-so No. 88 is changing its place in the system, from a forced labor camp to a local detention center according to the current needs of the state.

In any event, while the system remains dynamic, it is decades old and likely in need of substantial reform. Newer facilities, realignment of the major camps, and a more modern incarceration process would actually be beneficial from regime's standpoint in numerous ways.

Regardless, even a partial closure of a prison usually means a partial release of prisoners (as others are transferred elsewhere). For those that may see their sentences ended, this change is only good news.

--Jacob Bogle, 3/6/2021