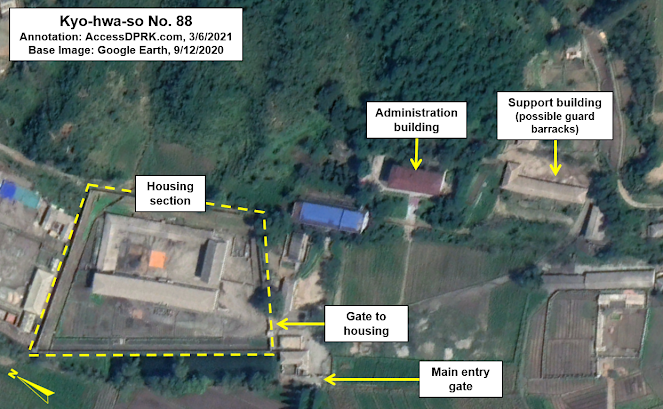

Located in the mountains west of the city of Sunchon, near a village called Unbong-dong, is a little-known reeducation labor camp (kyo-hwa-so) at 39.436033° 125.795551°.

Kyo-hwa-so are for those prisoners the regime considers "redeemable". Detainees are required to undergo ideological training and must endure forced labor. According to the UN Human Rights Council Commission of Inquiry report, detainees are also likely to experience beatings, torture, sexual assault, and starvation rations.

Several kyo-hwa-so have been the subject of detailed reports through the work of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea and other organizations, but the Sunchon facility has no known survivors to offer up witness testimony. It was mentioned in the 2017 report Parallel Gulag, but I would like to take this opportunity to lay out its developmental history in detail.

Despite the sparsity of direct information, it is known that the prison is a gold mine that relies on forced labor. And through the analysis of satellite imagery, a lot more can be learned.

The earliest commercially available high-resolution image of the camp is 2002. A review of Landsat imagery shows activity at the site in 2001, but there's little indication of a prison or mining activity prior to that; although, there is low-level deforestation at the site beginning in the late 1980s. If the prison existed before 2000, it was quite small.

In the December 9, 2002 image, buildings exist at the prison site but there are no obvious security features such as a fence or perimeter wall, and no obvious guard posts.

This site is one of the first of what will become an extended mining region, and another mine entrance exists at this time 1.3 km to the west at 39.442718° 125.781264°.

The next available image is from 2006. By then, a perimeter wall clearly surrounds the detainee facility and encloses an area of 1,400 sq. meters. The building covers approximately 280 sq. meters. The main mining facility and tailings pond were also enlarged.

Elsewhere in the immediate region, additional mining sites have opened up by 2006, but none appear to be prisons.

By May 2009, a new wing of the detainee facility was constructed, enlarging the building to approximately 370 sq. meters. This could indicate an increase in the number of detainees held at the prison. Also, the two corner guard towers were reconstructed.

Additionally, a small building immediately to the east of the detainee facility was razed.

The main mining building was also reconstructed and takes on the appearance of a typical ore processing plant, and a second tailings pond was opened.

By September 2010, where the building was razed in 2009, a new building was constructed in its place. The new building is ~210 sq. meters which is more than double the size of the older building. It could be associated with the prison's administration, but that can't be said with certainty.

Based on the tailings ponds, mining activity during this period was being carried out at a consistent pace.

Between 2011 and 2013, the detainee facility was enlarged yet again, with a further 80 sq. meters added.

Activity at the other nearby mines also increased at a similar rate to the activity at the kyo-hwa-so mine.

Between 2016 and 2017, a fence was added to partially block off the mine from the rest of the surrounding area. Prior to this time, there was no clear delineation between the mine's territory and the outside, civilian area.

Construction also took place at the detainee facility, with the addition of new walls (although incomplete in September). That work was finished in October 2017, bringing the size of the building to approx. 500 sq. meters.

By the end of 2019, a more robust perimeter fence was constructed around the mine, completely enclosing it, and three guard towers were also added.

Between 2020 and 2022, the main administrative building of the mine was reconstructed. The mining facilities were also further developed.

Based on the imagery, prisoners are transported from the walled detention facility to the mine via truck. The distance from the gate at the detention facility to the gate at the mine's fence is only ~36 meters, and then it's a further ~90 meters to the primary ore processing building.

The other mines in the area have all been further developed and grown, but none of them have indicators of being part of the kyo-hwa-so, and thus likely do not use forced labor.

Citing the Database Center for North Korean Human Rights, Parallel Gulag says that this kyo-hwa-so has an estimated detainee population of 400. Given the multiple expansions of the detainee barracks, I think it's possible that this prison now holds as many as 600 people.

Between the large kwan-li-so concentration camps, kyo-hwa-so reeducation camps, pre-trial detention centers, local labor training centers (rodong kyoyangdae and rodong danryondae), and military prison camps, North Korea operates a constellation of several hundred* penal facilities. The eight largest prisons are estimated to contain 205,000 detainees.

As evidenced by the Sunchon kyo-hwa-so, these detainees aren't simply serving a prison sentence but are used to help supplement state revenue. Millions of dollars' worth of gold and other minerals are extracted, and military uniforms, textiles, foodstuffs, furniture, shoes, and numerous other products are produced in the country's prisons. The revenue from those products can then be used by the Kim Jong Un regime to fund its other activities.

Although some prisons have been closed in the last 15 years (the Hoeryong and Yodok camps), Pyongyang has merely been consolidating its prison camp system and putting resources into extracting as much as possible out of its captive population.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters who help make all of this possible: Alex Kleinman, Amanda Oh, Donald Pierce, Dylan D, Joe Bishop-Henchman, Jonathan J, Joel Parish, John Pike, Kbechs87, Russ Johnson, and Squadfan.

*Note: the Ministry of Social Security and the Ministry of State Security each operate short-term detention/interrogation facilities in nearly every county in North Korea. Additionally, the full extent of military-operated camps (such as Camp 607) and local "labor training centers" has not yet been discovered.