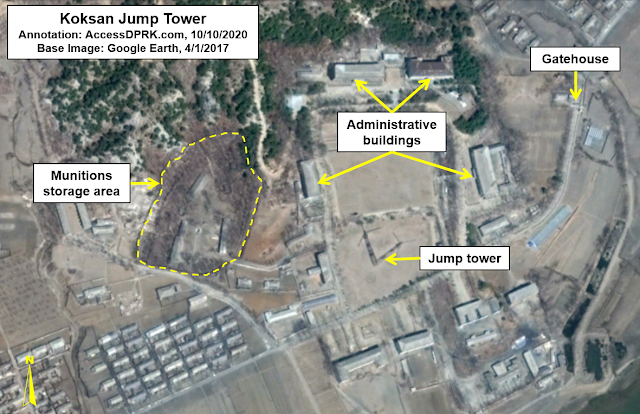

Under Kim Jong Un, four new ones have been constructed and three of the older facilities have undergone new construction and other improvements.

The AccessDPRK blog is dedicated to exposing North Korea via satellite imagery. Discussing domestic, economic and military locations and helping to uncover this hermit kingdom.

Thursday, October 15, 2020

North Korea's Airborne Training Sites

Under Kim Jong Un, four new ones have been constructed and three of the older facilities have undergone new construction and other improvements.

Sunday, September 27, 2020

Open-Air Theaters Spread Across the Country

A hallmark of Kim Jong Un's rule has been the creation of entertainment centers. Be they amusement parks, ski resorts, children's traffic parks, and even "4D" theaters, new recreational facilities have popped up all over the country.

Included in that mix are open-air theaters. Coinciding with the renovation of the Pyongyang Youth Open-air Theater, new theaters are under construction in nearly every provincial capital and some select other cities. In Chongjin, Haeju, Kanggye, Nampo, Pyongson, Rason, Sariwon, and Sinuiju, construction is well under way or nearly completed. Hamhung's theater is in the very initial stage of construction, and Wonsan already has an established open-air theater.

The construction of most sites began in 2018 but has yet to be fully finished at any of them except for the refurbished Pyongyang theater.

Plays and film have always loomed large in North Korean culture with nearly every town having a traditional movie theater built/rebuilt almost immediately after the Korean War. Kim Jong Il, especially, loved movies, plays, and opera. He wrote numerous letters and books on the subject, including On the Art of Cinema and On the Art of Opera. Each explaining in detail his views on the subjects and how they can best serve the state's goals through "socialist art" and as tools of indoctrinating the people with correct forms of thought.

And while everyone in the country knows they're being propagandized to, a lifetime of exposure has taught them to tune out the obvious stuff and enjoy the stories themselves. Indeed, North Korean's are quite the vocal art critics - in their subtle ways to avoid accidentally criticizing the regime. A good film, play, or song will rapidly make its way through the cities and into the countryside.

Soon after Kim Jong Un came to power, in recognition of the people's love of film, "4D-rythmic" theaters began to be built and now there's one in most large cities. With their distinctive architecture, they're easy to spot.

Participation in "mass-based art" has long been promoted with, "All provinces, cities, counties, industrial establishments and cooperative farms across the country have halls of culture, libraries and reading halls. Theatres and halls of culture in different parts of the country are equipped with facilities and musical instruments necessary for cultural and emotional life and artistic activities of working people." - Naenara, July 20, 2020

There is some variation in size with each of the new open-air theaters, ranging from 65-80 meters front-to-back and 85-100 meters at the widest. The existing Pyongyang theater is approximately twice the size as the newly built ones.

In the case of Sinuiju, there are 38 rows of seating arranged on three levels and into 13 sections. The Pyongyang Youth Open-Air Theater has seating for 10,000 and the theater in Haeju is said to have a seating capacity of 5,000. Given that Haeju is closer in size to the others, all of the new theaters probably have a seating capacity ranging from 5,000 to 7,000.

These theaters are also used for things other than plays and performances. Films can be shown, lectures given, and educational classes are provided. This not only makes them an important part of North Korean culture but they also provide the state with another venue for instilling propaganda and disseminating the wishes of the Korean Workers' Party.

The Pyongyang theater had a set of solar panels added to its roof. It is likely that the other new theaters will also include solar power. This fits in with the country's incremental adoption of green energy solutions to their otherwise extreme electricity shortage.

Provincial capitals usually have a handful of distinctive features (like joint murals of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il) that other cities tend to lack. However, certain things eventually make their way into other important cities after their popularity has been assessed in the capitals. I wouldn't be surprised if these open-air theaters end up spreading to a few more cities in the coming years.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters: Amanda O., Andres O. GreatPoppo, John Pike, Kbechs87, Planefag, and Russ Johnson.

--Jacob Bogle, 9/26/2020

AccessDPRK.com

JacobBogle.com

Facebook.com/accessdprk

Twitter.com/JacobBogle

Wednesday, September 16, 2020

Markets Still Grow Despite Economic Headwinds

Researching North Korea's economic development is always fraught with difficulties. The state offers very little in the way of concrete data, and state media predominantly focuses on single items (like a factory or amusement park being built) and gives exaggerated reports on national trends. At least, until Kim Jong Un came to power.

While the amount of reliable information is still sparse, Kim Jong Un has broken with tradition and hasn't been afraid to speak openly about the difficulties facing the country. He has even blamed the bureaucracy itself on occasion instead of always chalking up problems to sinister western forces or on a single bad administrator.

It is clear that the people's lives have improved since the days of Kim Jong Il but to what extent that trend has carried on into the last few years is murky and appears to be fairly uneven. How much the civilian and military economies have undergone structural changes under Kim Jong Un is likewise murky. However, all one has to do is pull up Google Earth to see billions worth of construction activity over the years, and to examine their missile tests to tell that Kim has certainly surpassed his father in the military sphere.

Now, before you start accusing me of calling Kim Jong Un a reformer, I'm not. But it is irrefutable that his governing style - while still autocratic - is somewhat different from that of his father's. Many of the obstacles and opportunities facing this generation are also fairly different than the ones facing the famine generation, so, naturally, the economic dynamics are going to change.

Markets for things like handicrafts have always been allowed in North Korea, but markets for selling grain, consumer goods, etc. were forbidden. That all changed during the course of the famine when farmers' markets popped up along roadsides across the country as people picked survival over obeisance to the state. In turn, the government has sought to regulate them (thus giving tacit approval to their operation), and according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), the state earns between $60 and $70 million annually from fees and taxes imposed on the markets as of 2018. Over the past decade or so the number of approved markets has roughly doubled, and as of this year, I have been able to identify 443 of them.

How much of this can be attributed to the fact Kim was left an "inheritance", reportedly worth up to $5 billion, that he was able to invest in weapons and economic construction, how much is due to illicit trading activities, and how much may be due to a civilian economy that has become even more market-oriented despite the regime's protestations can't fully be known. Regardless, the results are the same.

To demonstrate that the civilian economy is still growing despite internal and external economic pressures (including sanctions), I want to show some changes that can be seen in 23 markets across the country. (A list of these markets can be found at the end of the article.)

These changes have all taken place from 2015 to 2019 and includes markets in major cities and in more rural areas. The changes are: the building of entirely new markets and the expansions of existing ones.

Since 2015, at least thirteen new markets have been constructed with a combined area of approximately 47,271 square meters (508,820 sq. feet) of new selling space. The largest of the new markets was constructed in Chollima (Kangson) in 2019 and ranks among the largest markets in the country, covering 15,920 sq. m (171,361 sq. ft.).

Additionally, since 2015 at least eight other markets have undergone relatively substantial expansions, and two more were converted from open-air markets to being housed in buildings. Between the expansions and added covered floor space, the total additional area equals 18,906 sq. m (203,502 sq. ft.).

The result of these changes is that there has been an increase of 66,177 sq. m (712,323 sq. ft.) worth of market space in just four years.

According to CSIS, the largest market in the country generates the equivalent of $36/sq. m in revenue to the government each year. If we make a simple assumption that these new spaces will generate only $15 per square meter, that still represents nearly an extra $1 million a year going to Kim Jong Un's coffers (solely from fees and taxes at the markets). The regime generates additional revenue through the process of transporting goods, trading permit fees, paying bribes to border guards and officials, etc.

The fact new markets were also built after 2017, when economic sanctions against North Korea reached their height, tells us that the country's domestic economy and illicit trade is likely more robust than is generally thought.

This is backed up by Panel of Expert reporting by the United Nations that claims the country could be illegally importing three to eight times the amount of petroleum products it is legally allowed. That also helps explain how the regime has been able to build scores of gas stations in recent years which are estimated to consume the equivalent of the country's entire legal fuel import amount. Other illicit trading involves coal, seafood, and even sand exports.

And while COVID-19 has placed a tremendous strain on the economy, North Korea is still managing to build the largest hydroelectric project in its history, construction of the Pyongyang General Hospital is nearing completion, and the capital has embarked on a housing building boom.

Additional projects like multiple small hydroelectric dams, large collective farms (such as the Jangchong Vegetable Farm), and various construction projects that can be found in most medium and large-sized towns, all point to a country that is not stationary.

Clearly, the misallocation of resources on things like nuclear weapons and future missile tests places a burden on economic growth. And the extremely poor state of the country's electrical grid, transportation system, and healthcare network means the country is in many ways still trying to fully recover from the downfall of the 1990s, but economic progress can nonetheless be seen.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters: Amanda O., Anders O., GreatPoppo, Kbechs87, John Pike, Planefag, Russ Johnson, and Travis Murdock.

--Jacob Bogle, 9/14/2020

AccessDPRK.com

JacobBogle.com

Facebook.com/accessdprk

Twitter.com/JacobBogle

Friday, August 21, 2020

Renovations at Elite Hot Springs Appear on Hold Due to Economic Pressures

Thursday, August 13, 2020

History of the Musan Iron Mine

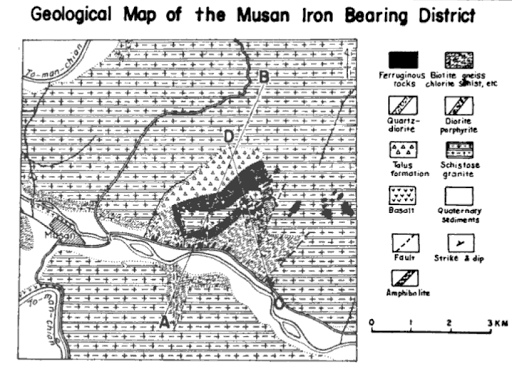

The area of heaviest deposits in this 1952 map covers approx. 247 square hectares (0.97 sq. miles).

|

| Musan Iron Mine as seen from Landsat in 1984. |

|

| Musan Iron Mine as seen via Google Earth in 2019. |

Friday, July 24, 2020

Wollo-ri: Much Ado About Something

Note: to save this report and read it later, you can download the PDF version here.

On July 8, 2020, CNN reported

on research done by experts from the Middlebury Institute of International

Studies on a facility in the village of Wollo-ri (near Pyongyang) that claims

the facility is part of North Korea’s nuclear program and is likely involved in

either warhead production or warhead storage.

Jeffrey Lewis and fellow researchers

Catherine Dill, David LaBoon, and Dave Schmerler then published a more detailed account of their line of reasoning on the Arms

Control Wonk blog. The post listed a number of visual signatures about

Wollo-ri that led them to suspect the facility was part of the country’s

nuclear program. That suspicion was then bolstered by a mention in Ankit

Panda’s new book Kim Jong Un and the Bomb, in which Panda says that the US intelligence

community assesses that there is an undeclared nuclear facility in Wollo-ri.

Having that public mention of the facility led to Lewis et. al going public

with their own research.

After the reporting, a number of

experts commentedA and gave the general view that there is nothing

specific to Wollo-ri that would make it a suspected nuclear facility. I happen

to agree. However, there hasn’t been a point-by-point counter-analysis of why

some experts may disagree with the assessment by Lewis et. al. That is the

purpose of this report.

Before I go on, I want to be clear

that none of this should be construed to mean that Wollo-ri isn’t a

nuclear facility. It might be and it might not be. What I am attempting to show

is that while the possibility exists, the probability of it is low based

on the available evidence (especially whether it’s a storage facility), and

that more research needs to be done before coming to any conclusion.

In the Arms Control Wonk post, five

points are listed to support the group’s conclusion that this facility is

likely an undeclared nuclear site. I would like to go through each of those

points and give my reasoning for why I don’t think they are necessarily, either

individually or collectively, direct signatures of a nuclear facility.

The signature elements described are:

1. A strong security perimeter

2. On-site housing

3. Monuments commemorating

unpublicized leadership visits

4. The existence of underground

facilities (UGFs)

5. Lewis also uses a description by US

officials in September 2018 that talk about an undeclared warhead storage

facility. The unnamed officials are cited

as saying North Korea “built structures to obscure the entrance to at least

one warhead storage facility” and that “the U.S. has also observed North

Korean workers moving warheads out of the facility.”

On the security

perimeter

The facility is surrounded by a wall

that runs along the full perimeter of the site and is approximately 1,460

meters long. Lewis points out the fact that the nearby Ryongaksan Spring Water

Factory doesn’t have any such perimeter wall, and so the wall’s existence helps

to key us onto the fact that the facility is important.

Typically, this is true. Most civilian

facilities lack a defined perimeter. However, many military sites lack them as

well. In fact, few military sites have more than a guard post at the entrance

let alone full perimeter security. There is even an artillery base located a

mere 60 meters from Wollo-ri’s perimeter that doesn’t appear to be surrounded

by anything; no wall, no fence, nothing.

And while most civilian sites lack a

wall, some do have one. An example is the nearby Mangyongdae Chicken Farm (39°

2'47.29"N 125°38'44.50"E) which has its own 2.9-kilometer-long wall.

When examining known nuclear-related

facilities, we do find that most have a perimeter wall. The Pyongsan

uranium processing and milling plant has one, each of the laboratories and

research compounds within Yongbyon

have their own walls, and sites associated with their WMD/missile programs also

have them like the Kim Jong Un National Defense University. But while looking

at these places, a key difference between them and Wollo-ri becomes apparent.

The Wollo-ri facility has three entrances into the complex. There is a primary entrance at the southwest corner and then two others along the eastern portion of the wall. Every other known and suspected nuclear facility only has one direct entrance, including the suspected uranium enrichment site at Kangson which Lewis described in 2018.

The entrances at Wollo-ri are also

fairly basic and do not appear to include anything substantial blocking the

entry points, just small guard huts. No gate or movable fencing to impede

forced entry.

Having multiple entry/exit points

raises the security risk that something could be stolen. And having multiple

sets of guards raises the risk that someone could be bribed to let in an unauthorized

person(s).

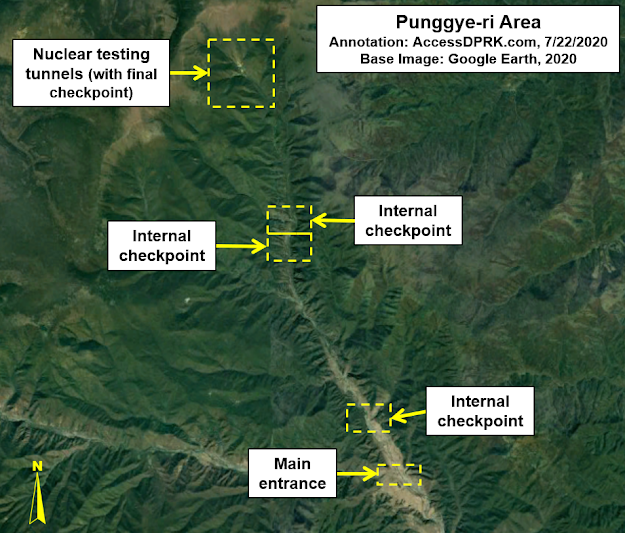

Facilities like Yongbyon and the

Punggye-ri nuclear test site, where substantial nuclear components and functional

nuclear devices are held, take a multilayered approach to security. To get to

the actual testing tunnels at Punggye-ri, one has to travel along several kilometers of narrow road and make it through multiple

checkpoints. If Wollo-ri is where nuclear warheads are either being produced or

stored, only the strictest security measures make sense.

Of on-site housing

Using Kangson as an example, Lewis cites what are likely apartment blocks within the perimeter as evidence that the facility may be part of the country’s nuclear program because having on-site housing (within a walled complex) is quite rare, and Kangson also has on-site housing. On-site housing is indeed unusual in North Korea but most nuclear facilities, in fact, do not have such an arrangement. Neither the Pyongsan or Pakchon uranium milling plants have housing, Yongbyon is a closed city with a defined housing district but no housing within the individual research and production areas, and the Academy of National Defense Science (Sanum-dong) lacks it as well. Other sites may have housing but part of that is due to the expansive size or remoteness of the facilities in question.

To be short, on-site housing at any

facility would indicate it has some level of importance, but it is not a unique

identifier of nuclear facilities.

Another thing to consider is how the

housing relates to Wollo-ri’s potential purpose.

Wollo-ri lacks any obvious substantial

electrical infrastructure which would point to the existence of

energy-intensive industrial activity or to a large underground facility. When

the site at Kangson was constructed, an electrical substation was built nearby

as well to help provide the needed electricity. Lacking its own substation or

major transmission lines, this would suggest that whatever is going on at

Wollo-ri wouldn’t be intense industrial activity or producing large numbers of

parts.

At the same time, there are six

apartment blocks at the facility. I estimate that there are as many as 406

apartment unitsB; each given to a worker and their family. Assuming

some couples work together, let’s make it an even 450 employees.

North Korea’s nuclear inventory has less

than 100 warheads and it is estimated that they can produce no more than twelve

bombs per year at maximum output. The country already possess an industrial

base known to produce a range of electrical components for their ballistic

missiles and other weapon systems, and more dangerous components (like the

explosive lenses) are manufactured elsewhere, so an undeclared production

facility would likely be used in the production of specialty parts. But you

wouldn’t necessarily need 450 employees to produce a handful of small devices

each year.

The monuments

Monuments can be an indicator of the

importance of a facility. Whether it educational, industrial, agricultural, or

military, the type of monument(s) seen at a site can help give a fairly

unambiguous ranking for the place. They can also indicate if Kim Jong Un (or

his predecessors) has visited before.

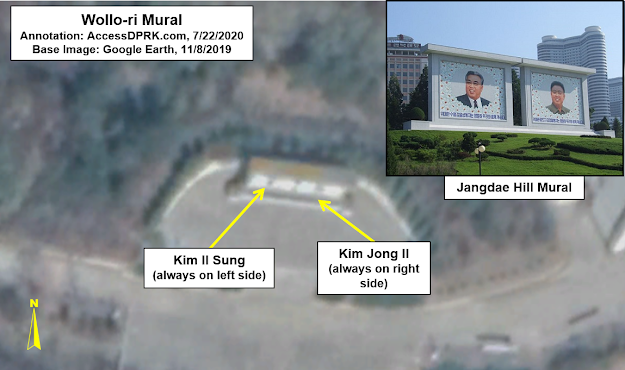

Wollo-ri possesses two monuments: a

Tower of Immortality and an apparent joint mural of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong

Il.

Towers are found in every town in the

country and they are dedicated to the “eternal” lives of Kim Il Sung and Kim

Jong Il. They can also be found at universities, factories, and other sites the

regime deems worthy. During my 2019 survey

of North Korean monuments, I found at least 5,175 Towers across the country.

Joint murals are found in county seats

and at even more rarified civilian and military facilities.

In some places you can clearly see the

faces of the Kims through satellite imagery. Unfortunately, the mural view at

Wollo-ri isn’t the greatest quality. But what is obvious is that there are two

images being shown (interpreted as busts of the Kims) and the rest of the

monument’s surface appears to be white. This is indicative of a joint mural.

Unlike the thousands of Towers, fewer than 300 were identified during the

monument survey.

The existence of the mural at Wollo-ri

is important, however, it isn’t a signature of a nuclear facility, even when

combined with the Tower. The headquarters

of North Korea’s air force has at least seven monuments and a joint statue of

Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il, the highest honor any North Korean site can be

bestowed. The headquarters also has a defined perimeter and on-site housing.

In the Arms Control Wonk post, it is

claimed that the monuments at Wollo-ri indicate visits to the facility by the

country’s leadership. That is simply incorrect. As I have described, Towers and

joint murals are found in many locations and none are directly connected to

leadership visits, rather, they are daily reminders of the Kim family cult and (when taken in combination) can ascribe a

level of importance to a given site. Commemorative monuments are much smaller

and are typically rectangular blocks of stone with a brief inscription carved

into the surface.

These can be found at many (but not

all) places visited by the Kims. In the event of multiple visits, instead of

having an ever-growing wall of monuments, a museum will be built. This was the

case with Korean People’s Army Farm No. 1116 which has received annual visits by Kim Jong

Un since 2013. Even if visits to Wollo-ri weren’t publicized, the facility

would still be awarded with a monument.

Wollo-ri only has the Tower and mural.

Underground

facilities

In the most simplistic terms, an

underground facility (UGF) could be defined as any useful structure with an

inch of dirt placed on top. However, most wouldn’t consider a root cellar or

simple basement a genuine underground facility. Particularly for the purpose of

secure and clandestine manufacturing or storage, underground facilities are

located multiple meters below the ground if they are placed underneath an

existing building or they are excavated deep into hills and mountains.

North Korea probably has more

identified underground sites than any country on earth. Some are enormous arms production

facilities (like the Kanggye General Tractor Plant, the largest known

underground arms manufacturing plant in North Korea) and others are smaller

facilities used for storage or that sit empty until needed in the event of a

conflict. They are all clearly identifiable once you know what to look for.

There are two hardened structures at

Wollo-ri at the front end of the complex that were built in 2011-2012.

(Coordinates: 39° 3'9.59"N 125°37'8.36"E) Neither is larger than 20

meters wide and there was no evidence of excavation work during their

construction to suggest they cover an underground entrance. Small hardened

structures like these are common enough and are often used to store fuel or for

other benign purposes.

There is also a small trench-like

structure that is barely two meters wide that lies in the northeast section.

(Coordinates: 39° 3'19.82"N 125°37'15.41"E) It does not connect to

any building and doesn’t match the design of any other underground entry point

one can find throughout the country. If it is supposed to be part of a UGF, I

would say construction is just in the initial stages.

Most underground facilities are easy

to spot.

One such facility is between the cities of Pyongsong and Sunchon, beneath Mt. Sonje. It has four entry points and there are piles of debris that were excavated from inside the hill during construction.

In other cases, where a building hides

the entry point, the building is flush with the hillside. None of the main

buildings at Wollo-ri are flush with the hillside. The other buildings at

Wollo-ri could only hide a UGF that was constructed directly beneath them and

there is no evidence of that having occurred. (Construction wasn’t caught on

imagery and no large debris piles are evident.)

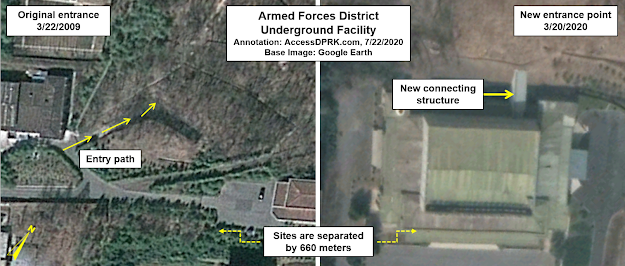

In the event where you connect a UGF

to a building that isn’t flush with the surrounding landscape, a connecting

structure is built. A prime example of that is a connecting tunnel that was

built in 2017 and connects a building in the Armed Forces District of Pyongyang

to a massive underground complex. It is approx. 6 meters wide and extends a

maximum of 20 meters to reach the hill. Prior to this connecting structure, the

main entrance, 660 meters away from the newer one, was still identifiable.

Warhead storage

possibility

Lewis’ addition of the description

of an unidentified nuclear warhead storage facility is interesting but there

was nothing in the description that mentioned Wollo-ri or that gave a specific

location. The officials simply said there’s a warhead storage site somewhere.

In terms of storage, there are other more suitable places suspected of being

warhead storage facilities, including one near the city of Kusong.

And when looking at known warhead

storage sites around the world, a few trends become clear. Namely, very tight

security and underground storage. The largest warhead repository in the world

is the Kirtland Underground Munitions and Maintenance Storage Complex in the

scrublands around Albuquerque. The underground portion alone covers roughly

57,000 square meters (not including the potential for multiple levels).

It has a single entry point, it is surrounded

by fencing, and has three watchtowers. Plus, it is situated in the middle of a

larger military complex.

Turkey’s Incirlik Air Base is another place that houses American/NATO

warheads (up to 50). They are stored underground in the center of the air base

which is the most secure area.

The lack of any identifiable

underground facilities at Wollo-ri, its questionable security, and the lack of

any direct mention of the site specifically as a storage facility leads me to

conclude that while it may have a role to play in North Korea’s nuclear

program, the probability of it being a warhead storage facility is almost zero.

Adding to that assessment are the additional facts that Wollo-ri is located far

away from any long-range missile bases and the fact that it is located just a

few miles of an elite section of Pyongyang.

In order for North Korea’s ballistic

missiles to be a credible threat, they must be near the warheads. Wollo-ri is

nearly 70 km away from the nearest known ballistic missile base and that

journey would take hours across miles of winding road and rail – an easy target

to destroy.

And while North Korea does have a

habit of meshing military and civilian areas together, any direct hit to a

nuclear storage site would spread radioactive material across a wide area

thanks to fire and wind currents, contaminating the city with highly enriched

uranium and/or plutonium (depending on the type of weapons stored there).

Political University?

I’d like to briefly discuss an

alternative explanation put forth by an alleged North Korean official. He claimed

that the facility is actually the “Pyongyang Anti-aircraft Unit Command’s

Political Military University”. I and many others deeply question this

explanation. There is a state security academy nearby at 39° 2'39.39"N

125°38'1.49"E, and it and all of the other known political and security

schools follow a very specific pattern. Wollo-ri does not comport with that

pattern and deviates from it in a number of ways. While I am not convinced that

Wollo-ri is a nuclear-related facility, I reject the assertion that it is a

mere political university.

Conclusions

While there aren’t any other “unusual”

facilities around Wollo-ri that could instead be the nuclear facility, the

evidence provided for the site in question, in my estimation, doesn’t rise to a

likely probability – particularly when it comes to the question of it being a

warhead storage site. The specific parts of Wollo-ri described are common to

many other facilities (military, industrial, and educational), and it seems the

claim rests largely on the book mention, for which other questions need to be

answered before having the confidence to connect the intelligence assessment

with this specific location.

Even when looking at all of the

signatures discussed on the Arms Control Wonk post in combination, the

perimeter, housing, monuments, etc. they don’t add up to a unique identifier.

To demonstrate this, one need only look at the Samchon Fish Farm (which

underwent an expansion in 2019). It, too, has a security wall, on-sight

housing, multiple monuments, and it also has its own electrical substation and

a water supply system that is partially underground.

But back to Wollo-ri. As a village it is unassuming, so the Wollo-ri facility certainly sticks out among the structures surrounding it. It just doesn’t stick out in any specific manner. There are also less conspicuous (aka not unusual looking) military facilities in the area, some that include underground sites, that could theoretically serve as a production site. (The underground facilities at the Panghyon Aircraft Plant are thought to have played an early role in the country’s enrichment program.)

Last note

On a personal note, I have never

openly debated the analytical work of anyone before, so I want to take a moment

to address this. Lewis and the other experts who took part in analyzing

Wollo-ri are brilliant. That’s rather self-evident when you look at each of

their careers. I am not saying they are wrong, rather, I disagree with the

conclusions drawn based on the evidence presented.

Wollo-ri is a “puzzle” in certain

ways, as David LaBoon told me, and I agree with that. The fact the village has

been mentioned in connection with the country’s nuclear program by an

intelligence official is intriguing, but the facility’s aspects are vague, yet

also show importance. Importance to what is the question.

As interest in North Korea grows and

the tools available for open-source intelligence improves, the body of work

relating to the country has exploded (pardon the pun). Having an open dialogue

about differing analysis creates a fuller and more nuanced picture and serves

to better inform the public and policy makers going forward.

Footnotes

A.

1.

Shin Jong-woo of the Korea Defense and Security Forum said,

"It may be a facility for another military purpose, not for nuclear

warhead development."

2.

Olli Heinonen, former deputy director general of the International Atomic

Energy Agency (IAEA) told Voice of America that there is little possibility that there

is a nuclear facility around Wollo-ri and that, “the report does not provide

clear evidence that the facility is nuclear-related.”

3.

A report

by the Korean Broadcasting Service also noted, “South Korea’s military and

intelligence authorities have dismissed a CNN report that said activity

suspected of being nuclear warhead production.”

B. There are five apartment buildings in a cluster and a likely sixth (that’s of a different layout) near the southern end of the facility. Each building is seven stories tall. Estimating the first five buildings have 10 apartment suites on each floor, that comes to 350 units. And the sixth building has eight suites or 56 units for the building. That totals 406 apartment units. Depending on the actual layout of the units, there could be fewer or substantially more.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters: Amanda O., Anders O. GreatPoppo, Kbechs87, Planefag, Russ Johnson, and Travis Murdock.