North Korea is perhaps the most militarized country in history. As a country roughly the size of the US state of Pennsylvania, it has literally thousands of distinct military sites: air defense, training bases, coastal artillery batteries, airbases, missile sites, tunnels, and much more. Because of the country's nuclear program, their missile bases receive a lot of attention. However, there is still a lot that is unknown about these sites, in part, because North Korea has only officially acknowledged a handful of them (and often just in vague terms).

The satellite facilities at Sohae, Tonghae and the Chiha-ri missile base are fairly well known, but the good folks over at Beyond Parallel (part of the Center for Strategic International Studies) estimate there may be as many as

20 undeclared ballistic missile bases and related support facilities. The

2017 release of "Phase II" of the

AccessDPRK mapping project listed over 9,500 military points of interest, and since then, I have begun work on the next part of the map which now includes an additional 1,500 military sites. Using this unpublished version, I decided to see what likely missile bases and large underground facilities exist in the country. (These stand-alone underground facilities are something Beyond Parallel isn't looking at.)

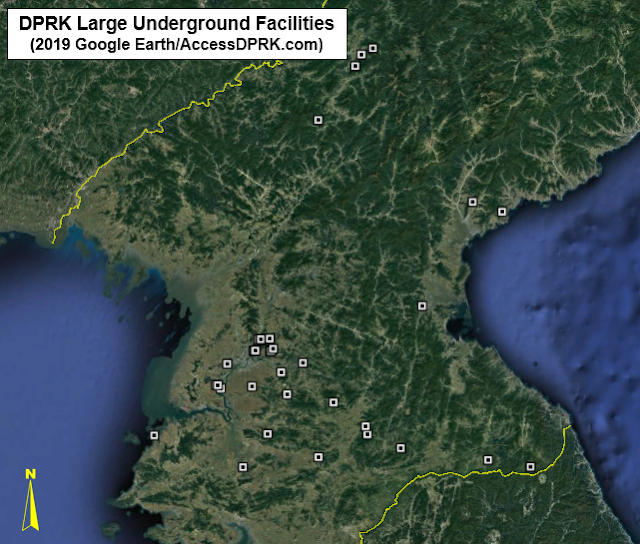

After going through every identified military base, tunnel, underground facility (UGF), known and suspected missile base, and other sites, I was able to locate 19 known and possible ballistic missile bases, the two satellite launch stations, and 39 large UGFs that are separate from the missile bases.

North Korea considered the creation of a ballistic missile program soon after the Korean War and it became an official goal as early as 1965, with Kim Il Sung saying the country needed to have rockets that could fire as far as Japan. From then until the early 1980s, the regime laid the foundations of the program including the acquisition of Soviet and Egyptian technology. In 1984 they were able to test their first indigenously produced missile which was a variation of the SCUD-B.

The height of their missile program came with the first internationally verified successful orbital insertion of a satellite into space in 2012, the

Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 Unit 2, followed by the 2017 test of the

Hwasong-15 missile which can reach nearly all of the United States.

The vast size of North Korea's missile program infrastructure (dozens of locations in a country the size of Pennsylvania) helps to ensure that they can continue to carry out attacks if one or several bases are destroyed during a war. It also makes it all the more difficult for Western powers to keep track of the movement of weapons and equipment.

By 2017 the country was thought to have around 900 short-range missiles, though that figure may have grown to 1,000+ with the

apparent development of a North Korea-produced clone of the Russian

Iskander missile. (As well as from the continued production of known missile systems.)

-

Short-range missile are typically defined as having a range of 1,000 km (620 miles) or less. Examples include the KN-02, Hwasong-6, and the aforementioned Iskander clone.

- Medium-range missiles have a range of 1,000-3,000 km (620-1,860 mi). Examples include the Rodong-1 and Pukkusong-2 (KN-15). North Korea likely has 500 or fewer of these missiles.

- Intermediate-range missiles can reach 3,000-5,500 km (1,864-3,418 mi). An example is the Hwasong-12. There are likely fewer than 250 IRMBs.

- ICMBs (intercontinental ballistic missiles) have a range exceeding 5,500 km (3,400 mi). North Korea's Hwasong-15 is their latest developed ICBM. There are probably fewer than 75 operational missiles in this category.

The country's missile bases are divided into three main "belts". They are, with increasing distance away from the DMZ the, "tactical belt", "operational belt", and "strategic belt". The different belts reflect the types of missiles deployed at each base, with the strategic belt holding long-range missiles (this includes the submarine base at Mayang) and the tactical belt being the site of shorter-range missiles aimed at the DMZ, Seoul, and other important South Korean sites.

Pyongyang's missile program is under the control of the Korean People's Army (KPA) Strategic Forces and the construction of the bases is done by KPA Unit No. 583 (the Military Construction Bureau). Substantial construction began for many of the bases in the late 1980s to mid-1990s, and construction at all sites had either already began or was scaled up by the 2000s. Several ballistic missile bases, such as Chiha-ri and Yusang-ni, have had upgrades since Kim Jong Un came to power.

A note on naming. Unless a name has been given in an official North Korean or US-ROK alliance intelligence source, all of the locations talked about in this article are otherwise named for the nearest populated place as listed by OpenStreetMap. A lack of standard naming has led to confusion for years, but that's one thing this article seeks to remedy. And, instead of simply saying "a base in Chagang Province" or "by Kimchon-ni" (when there are multiple villages with the same name), this article will list the base's exact coordinates.

These twenty-one main facilities occupy approx. 362 square kilometers of territory. Despite my best efforts, I wasn't able to positively identify the

To'gol base (allegedly in Pyongsan County) or the Kittaeryong base (in Anbyon County).

Within the "tactical belt" are:

1. Chiha-ri - Coordinates are: 38°36'10.63"N 126°44'12.20"E

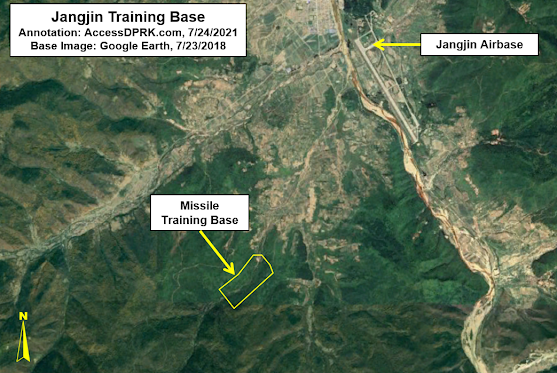

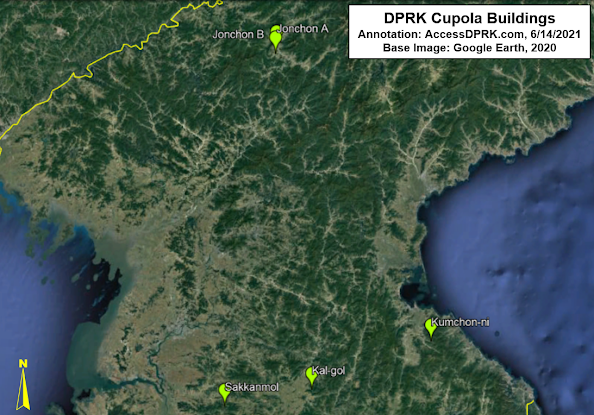

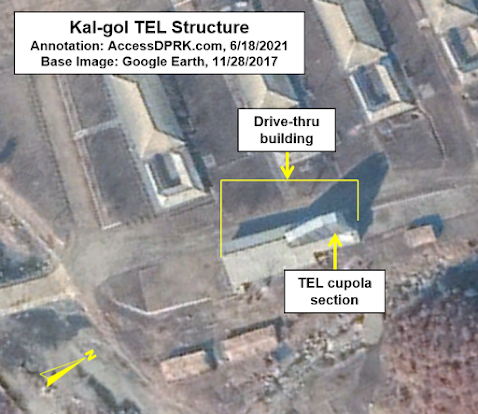

2. Kal-gol - Coordinates are: 38°40'3.15"N 126°44'49.97"E

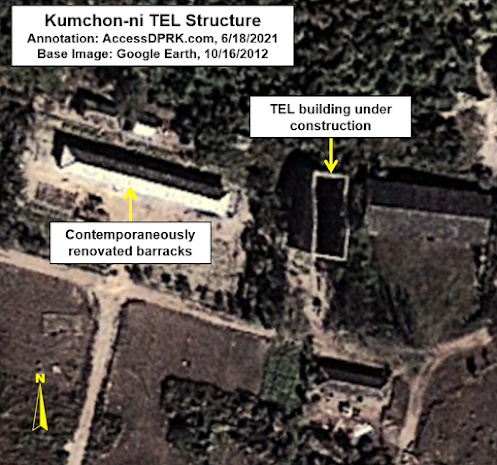

3. Kumchon-ni - Coordinates are: 38°57'54.14"N 127°36'8.48"E. Kumchon-ni has been detailed by

Beyond Parallel.

4. Sakkanmol - Coordinates are: 38°34'59.81"N 126° 6'29.91"E. Sakkanmol has been detailed by

Beyond Parallel.

5. Sing'ye - Coordinates are: 38°38'24.31"N 126°40'48.26"E. Sing'ye is one of the smallest missile bases in the country. It may also be the source name for the Hwansong-class of missiles as a nearby village is named Hwasong, and the base was constructed early on.

6. Suthae-ri - Coordinates are: 38°22'51.67"N 127°29'0.55"E. Suthae-ri is a possible base and hasn't been mentioned in any media that I could find. At less than 10 km from South Korean territory, it would be the closest ballistic missile base to the DMZ. The base doesn't have the "drive thru" bunkers that many other known bases have, but it does have a large and expanding underground facility and several bunkers of other types.

Chiha-ri, Kal-gol, and Sing'ye are all within 5 km of each other, which would lead me to believe that they are connected in some way; perhaps in mutual-supporting roles.

Within the "operational belt" are:

1. Hodo - Coordinates are: 39°24'30.31"N 127°32'5.63"E. The Hodo base is very small and is more for testing missiles than as an operating base during conflict. Hodo seems to have replaced the beaches at Wonsan for testing sort-range missiles, as the site at Wonsan is now a cluster of hotels.

2. Hwajil-li - Coordinates are: 39°11'52.58"N 125°23'56.93"E. Hwajil-li is listed by the Nuclear Threat Initiative as a missile base that was constructed in the 1980s. Current satellite imagery doesn't show anything that would suggest the site is currently used as a missile base. A basic air defense battery and associated facilities is all that exists today.

3. Ongpyong - Coordinates are: 39°19'33.69"N 127°19'50.68"E. It is a smaller base and its facilities may be dispersed throughout a larger area. There are ongoing questions about the site's true purpose, and it may not be a ballistic missile base but rather a support facility for region air defense sites.

4. Sil-li - Coordinates are: 39°10'49.68"N 125°39'48.84"E. Sil-li is located next to the Pyongyang-Sunan International Airport and is a "ballistic missile support facility", which is not the same as an "operational ballistic missile base". It was constructed from 2016-2020, and has been detailed by

Beyond Parallel.

5. Singsong-ri - Coordinates are: 39°21'32.23"N 125°45'49.57"E. Singsong-ri is a possible base. Like Suthae-ri, it doesn't fit the design of a lot of other known bases, but it does have three underground entrances which run deep into a mountain. If it is indeed a base, it's likely used to store missiles and equipment.

6. Yusang-ni - Coordinates are: 39°26'51.58"N 126°15'30.33"E. Yusang-ni has been detailed by

Beyond Parallel.

On average, the land area used by these bases is smaller than bases in the other two belts.

Within the "strategic belt" are:

This belt includes the country's two satellite launching stations as they have played a role in the development of ballistic missile technology and could be used as launching sites.

1. Hoejung-ni - Coordinates are: 41°22'21.64"N 126°54'46.14"E. Hoejung-ni is one of the newest missile bases to be constructed. It is only a few kilometers from the base at Yeongjo-ri

2. Kusong-ri (alleged) - Coordinates are: 39°59'51.22"N 124°34'16.80"E. According to Jane's/IHS, this surface-to-air missile base may also house some Nodong missiles; however, this has never been conclusively demonstrated and it is likely

only an air defense base based on the most recent satellite imagery.

3. Riman-ri (Yongnim) - It is the largest base by area and covers approx. 72 sq. km. Coordinates are: 40°29'2.94"N 126°30'1.65"E

4. Sangnam-ri - Coordinates are: 40°50'20.20"N 128°32'35.82"E. Sangnam-ri has been detailed by

Beyond Parallel.

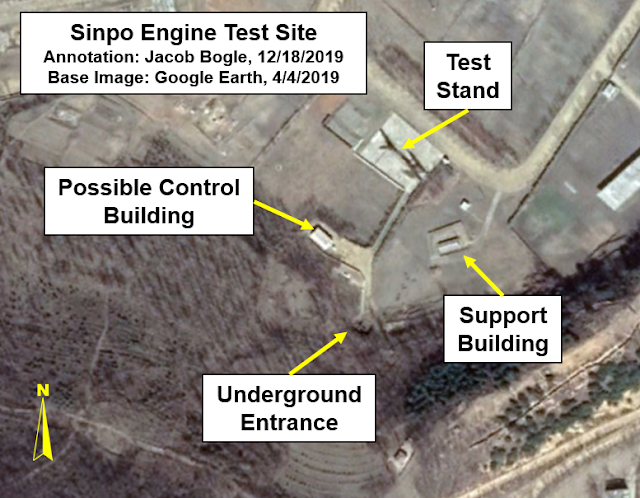

5. Sinpo-Mayang - Coordinates are: 39°59'42.09"N 128°11'43.98"E. Sinpo houses part of a large submarine base (the other half being on Mayang Island) and has a missile test stand. The base is where North Korea is developing their submarine launched ballistic missiles. The base is not an operational ballistic missile base where missiles would be fired from, but I have included it for its role in the development of SLBMs and the fact that any future SLBM-capable submarines would be based at Sinpo-Mayang.

6. Sino-ri - Coordinates are: 39°38'57.32"N 125°21'36.37"E. Sino-ri has been detailed by

Beyond Parallel.

7.

Sohae Satellite Launch Center - Coordinates are: 39°40'6.88"N 124°42'30.44"E

8. Taegwan - Coordinates are: 40°18'34.10"N 125°16'17.02"E

9.

Tonghae Satellite Launch Center - Coordinates are: 40°52'13.09"N 129°38'34.10"E. My discovery of a

missile test stand being constructed at the site was the basis of my very first

#AccessDPRK post back in 2013.

10. Yeongjo-ri - Coordinates are: 41°19'44.56"N 127° 5'35.38"E. Once considered a nuclear site, Yeongjo-ri is actually a missile base.

The next area I want to explore is the collection of large underground facilities (UGFs).

As mentioned earlier, these UGFs are not part of any obvious missile base. Underground sites abound in North Korea and serve as active and reserve storage sites for weapons, equipment, food, and other supplies, and they allow for artillery to be fired and then rolled back into the tunnel for protection against counter strike. There has been a lot of speculation about the number of tunnels and underground sites within the country with some estimates going as high as 100,000. Based on the work for

AccessDPRK, the real figure is much closer to 1,000 sites (some may have multiple entrances, but they're part of a single facility). Most of them are small and some are used as underground factories. But there are a few dozen (39 to be exact) which are much larger than any of the others (excluding underground industrial sites).

Some of them are placed at military bases and consist of a single complex while others exist as clusters, especially in Pyongyang.

There are four UGFs in Chagang Province.

1. Oil-rodongjagu UGF - 40°59'53.82"N 126°46'51.12"E

2. Janghang UGF - 40°57'32.66"N 126°41'9.98"E

3. Kanggye-Puji UGF - 40°53'12.75"N 126°38'4.45"E

4. Jonchon UGF - 40°32'49.08"N 126°19'48.21"E. This facility is across from the Riman-ri (Yongnim) missile base and so may be connected to it in some way.

There are three UGFs in S. Hamgyong Province.

1. Toksan UGF - 40° 1'52.84"N 127°35'48.28"E

2. Sinphung UGF - 39°58'7.64"N 127°50'17.89"E

3. Songhung UGF - 39°22'54.97"N 127°10'43.71"E

There are five UGFs in Kangwon Province.

1. Chongdu-ri UGF - 38°22'2.71"N 128° 2'20.19"E

2. Wondong-ri UGF - 38°24'51.14"N 127°41'59.76"E

3. Konsol-li UGF - 38°29'30.47"N 127° 0'7.53"E. The UGF here is part of a

new military base that was constructed in 2016-2017.

4. Jisang-ri UGF - 38°34'44.13"N 126°44'5.59"E

5. Kubong-ri UGF - 38°37'44.89"N 126°43'15.55"E

There are four UGFs in N. Hwanghae Province.

1. Phyongwon UGF - 38°46'42.16"N 126°27'47.77"E. This has a very large UGF and might actually be part of their missile infrastructure.

2. Taephyong UGF - 38°26'5.60"N 126°20'37.53"E

3. Misan-ri (Kyongje-dong) - 38°34'41.50"N 125°56'6.04"E. This is a set of two

enormous bunkers that would serve as a hardened helicopter base during conflict.

4. Okhyon - 38°22'4.16"N 125°44'22.81"E

There are 23 UGFs in Pyongyang. Eleven of them are in three clusters. Each cluster will only get one set of coordinates.

1. Pyongyang Group 1 - 39° 5'58.09"N 125°49'48.07"E. There are three large tunnels/entrances that spread out in an east-west line approx. 1 km long.

2. Pyongyang Group 2 - 39°10'11.96"N 125°51'28.16"E. This is a set of five large tunnels that are along a valley between two sets of hills. From the coordinate given, a rectangle is formed by a line running 1.4 km west to east and then from that point, north to south for ~0.5 km.

3. Pyongyang Group 3 - 39° 5'54.07"N 125°57'1.50"E. This is a group of three tunnels that are all located within the same hill, encircling it.

4. Pyongyang Single UGF - 39° 6'43.85"N 125°58'24.30"E

5. Taedonggang Large UGF - 39°10'25.07"N 125°56'43.60"E

6. Taedonggang Smaller UGF - 39°10'31.77"N 125°56'46.76"E

7. Samdung UGF - 39° 1'32.28"N 126°12'56.77"E

8. Rodgon-ri UGF - 38°57'54.22"N 126° 2'27.51"E

9. Sangwon UGF - 38°49'39.49"N 126° 5'23.32"E

10. Chunghwa UGF - 38°52'28.51"N 125°48'23.32"E. This UGF is within the

Air Defense & Combat Command HQ complex.

11. Sunwha UGF - 39° 0'52.08"N 125°36'15.03"E

12. Kanchong UGF - 38°51'34.16"N 125°33'15.48"E

13. Kangso 1 - 38°52'55.87"N 125°30'57.91"E

14. Kangso 2 - 38°52'46.98"N 125°31'48.32"E

Here are a few examples of these underground facilities.

Patreon Special Access

Patreon supporters at the $20 tier are entitled to exclusive datasets. The Google Earth file for this post is one of those exclusive offers. This is the only nationwide map of these facilities within the public domain that contain accurate geolocation data and additional information. The file also has over 300 specific sites of interest within the various missile bases for your research pleasure. Please consider supporting me on Patreon and get access to this and other exclusive datasets.

I would like to thank my current

Patreon supporters: Kbechs87, GreatPoppo, and Planefag.

--Jacob Bogle, 10/22/2019 (updated list, Dec. 24, 2020)

www.JacobBogle.com

Facebook.com/JacobBogle

Twitter.com/JacobBogle