If you've ever looked at a diagram of a nuclear bomb (whether of Little Boy or of a modern miniaturized warhead like the W-87), you might be forgiven for thinking constructing such devices looks fairly straightforward.

For a gun-type fission weapon (like Little Boy), you simply fire a hollow chunk of uranium at a solid cylinder slug of uranium, setting off a chain reaction. For a simple implosion-type weapon, you just wrap a core of plutonium in a shell of conventional explosives and detonate it. That will create an implosion shockwave, compacting the plutonium until it reaches criticality and explodes with the force of thousands of tons of TNT.

Even today's advanced two-stage thermonuclear weapons can be rendered in handy graphics. But the simplicity of popular descriptions of how nuclear bombs work belies their devilish complexity.

All of these descriptions and diagrams are simply distillations of feats of physics and engineering that took thousands of people and billions of dollars to produce in each of the countries that have developed their own weapons.

The world's nuclear weapons programs rely on physicists, engineers, often some of the most powerful supercomputers in history, and networks of manufacturing centers that are responsible for safely producing the uranium and plutonium needed as well as the scores of individual components that make up a working nuclear device.

In the United States, the primary assembly of nuclear warheads takes place at a single location in Texas. But that's just the final step in a long chain of research and production that involves facilities across the country, from the mountains of Tennessee to the deserts of New Mexico.

Likewise, North Korea's nuclear weapons program is a decentralized affair that includes mining sites surprisingly close to the DMZ to top secret underground storage facilities just a couple hours away from the border with China.

In this article, I will attempt (with a caveat) to layout North Korea's nuclear weapons infrastructure.

That caveat is: no country makes its nuclear secrets easy to uncover. Building a nuclear weapon takes the combined efforts of thousands of people, and uncovering the exact design components and in which factory which part is made is typically highly classified information. Because of that, this can't be a comprehensive exposé. There is still plenty about Pyongyang's nuclear program that isn't publicly known, and plenty that isn't even known to government intelligence agencies.

However, there is enough known information to provide a solid outline of many of the facilities North Korea uses to produce their nuclear arsenal.

With that in mind, let's get to it.

The first steps to building a bomb are in research and development. For North Korea, this takes place at several institutions including the Atomic Energy Department of Kim Il-sung University (39.059259° 125.767729°), the Physics Department of Kim Jong-un National Defense University (39.169623° 125.776838°), as well as three departments within the Pyongsong College of Science (the Chemical Department, Physics Research Institute, and Atomic Energy Research Center). Additional research also takes place at some of the locations I'll discuss in greater detail below.

Once you have the theories and designs worked out, you need some raw materials.

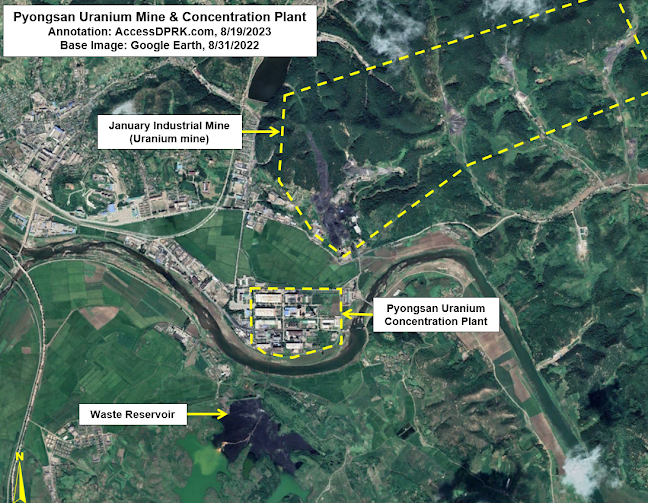

North Korea has modest uranium deposits and has mined it from locations across the country including at the Wolbisan Mine and at mines near Sonbong. However, North Korea's primary uranium mine is located in Pyongsan (38.323984° 126.436512°).

The Pyongsan uranium mine (also called the January Industrial Mine) is an anthracite coal mine that contains usable concentrations of uranium as an impurity. The mine has five mining shafts with one, possibly two, currently active.

From the mine, the ore is taken via a conveyor system about 500-meters-long to the uranium concentration plant and mill.

The people over at Arms Control Wonk and the Center for Strategic and International Studies have written in-depth reports on the history and workings of the Pyongsan Uranium Concentration Plant. But here's a brief rundown.

Construction on the plant began in 1985 and it was operational by 1990, albeit on a limited scale. Full-scale production wasn't reached until ca. 1995.

The ore is brought to Pyongsan where it is processed to separate out the uranium from the rest of the minerals found in the coal source material.

The uranium is found in reported concentrations of between 0.26% and 0.8%, and at least 10,000 tonnes of ore are mined each year; although, this estimate varies widely and annual production levels also vary year-to-year. This is then processed and concentrated into what's commonly known as yellowcake, which is 80% pure uranium.

The uranium extraction process involves (simplistically): crushing the coal, sampling, grinding it down into a powder, adding sulfuric acid and sodium chlorate to leech out the uranium, washing it, running it through an extraction circuit and salt solution, and passing it through precipitation tanks where the concentrated uranium can be gathered, and dried. The yellowcake is then packed and shipped off for enrichment.

After processing, as much as 272 tonnes of yellowcake uranium leaves the plant annually in the form of triuranium octoxide (U3O8) and uranium dioxide (UO2).

North Korea does have a second uranium concentration plant at Pakchon (39.710533° 125.568319°). It began operations in 1979 as a pilot plant, but has been in caretaker status since at least 2002, with only low-level activities noted from time to time, leaving Pyongsan as the only active uranium mill.

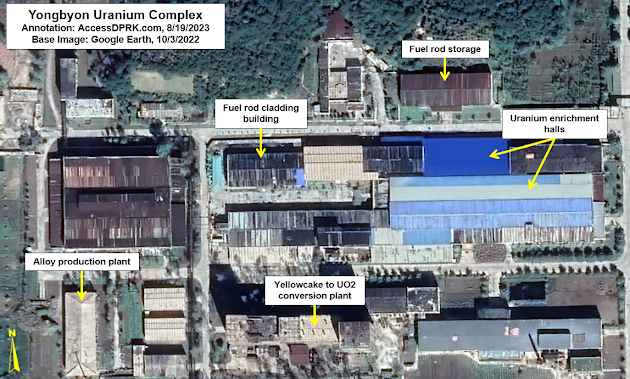

From Pyongsan, the uranium needs to be enriched. There is only one verified enrichment facility, at Yongbyon. There is a suspected site near Pyongyang at Kangson (38.957195° 125.612159°), but there is considerable debate within published sources about Kangson's purpose.

Other raw materials besides uranium are needed to support the country's nuclear program (from graphite to tungsten), but which mines exactly are used isn't known. However, there are several identified mines that could provide North Korea with some of the needed materials.

There are several specialty materials and components associated with uranium enrichment and modern warhead manufacturing that North Korea is not known to have the capabilities to produce domestically, but the country clearly has enough legacy technology and skill to overcome those shortcomings and to produce these deadly weapons.

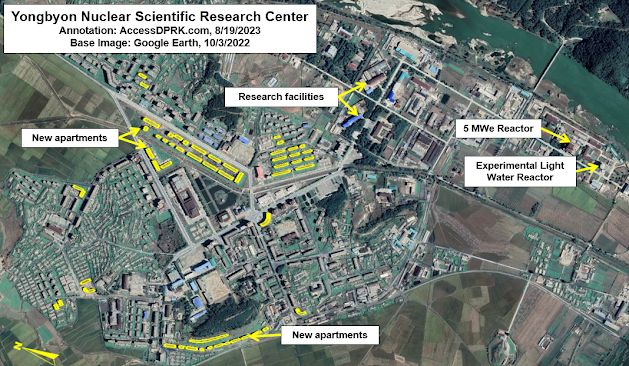

The Yongbyon Nuclear Scientific Research Center (39.796977° 125.755110°) is North Korea's key nuclear facility. With a history dating back to 1963-64, Yongbyon plays a central role the country's development of nuclear weapons.

Located some 85 km north of Pyongyang, the complex covers a 24.8 sq. km. area that's surrounded by fences and guard posts. Within Yongbyon lies the town of Dong-an (formerly Sang-dong) which serves as the civilian quarter and houses all the scientists, researchers, technicians, their families, and everyone else needed to run the town and research centers.

Southeast of the town is a walled compound containing the research center's administration, laboratories, and various other facilities. South of that, is an adjacent walled compound that houses the 5MWe nuclear reactor and the Experimental Light Water Reactor, as well as the spent fuel storage building.

Elsewhere in Yongbyon is the Radiochemistry Laboratory (39.781174° 125.753286°) where plutonium is produced as well as radionuclides used in nuclear medicine. And then there is the uranium fuel fabrication facility (39.770255° 125.749224°) where the uranium brought in from Pyongsan is further processed and enriched into weapons-grade material. The fuel fabrication facility is also used to manufacture the fuel rods needed for the nuclear reactors.

Estimates place Yongbyon's annual capacity to be 100 kg of highly enriched uranium and 6 kg of plutonium. The enrichment hall at the uranium fuel facility was enlarged in 2013 and again in 2021, indicating an increase in North Korea's enrichment activities.

According to the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, North Korea has enough fissile material to build a further 45-55 nuclear warheads.

Another change of note within Yongbyon has been the construction over the last decade of enough housing for ~3,200 new residents. The increase in Yongbyon personnel, the enlargement of the uranium fuel fabrication facility, and other changes in recent years (at Yongbyon and elsewhere) have enabled Kim Jong-un to ramp up the production of nuclear warheads.

This increase in capacity was reflected in a 2022 speech by Kim Jong-un in which he vowed to "exponentially increase" the size of the country's nuclear arsenal.

However, simply having a pile of enriched uranium and plutonium doesn't a nuclear bomb make.

Nuclear weapons use shaped charges made of conventional explosives as an "explosive lens" to collapse the inner shells within the device and lastly to compress the core of fissile material, initiating the chain reaction.

Yongdoktong (40.004320° 125.339377°), just east of Kusong, is where these lenses are developed, tested, and manufactured.

A review of Landsat images reveals that construction of the complex began ca. 1987 with most of the work completed by 1992. In more recent years, several changes have been noted including at least 18 new buildings or building renovations since 2016, the addition of greenhouse and garden facilities in 2019, and ~47 new housing units, most of which were built since 2020. On top of that, in late 2020, a new building was constructed to cover the entrance to an underground facility near the main production center.

Explosive lenses are often produced at or near the same facility that conducts the final assembly of warheads. The size of Yongdoktong, its several distinct sections and underground sites - to me - makes it a candidate location for where North Korea builds their completed nuclear warheads.

Additionally, it is where intelligence sources suggest that North Korea stores its warheads in underground facilities within the complex.

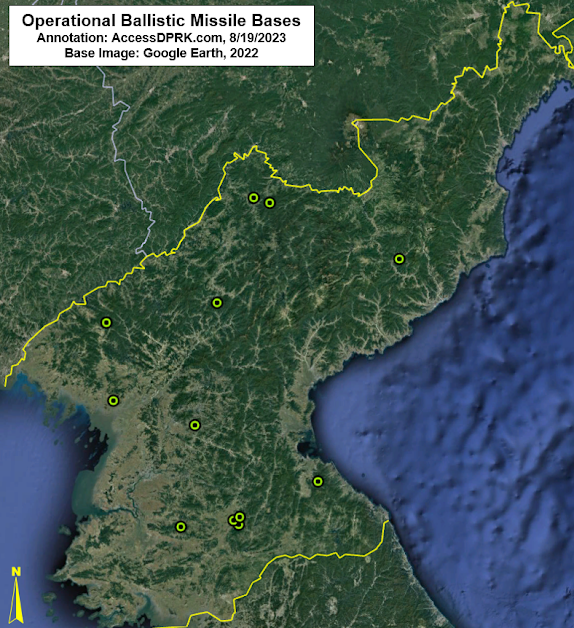

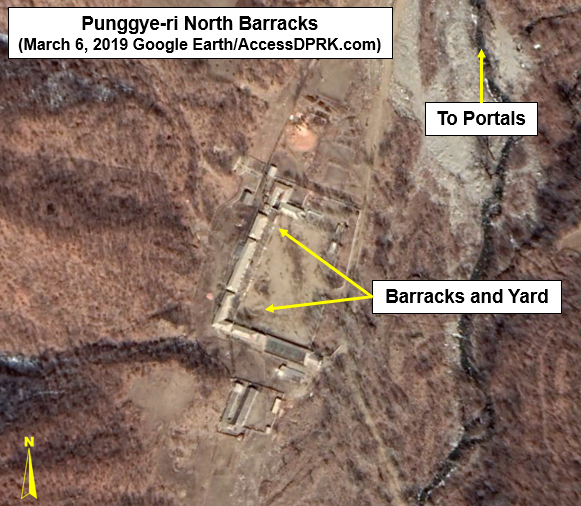

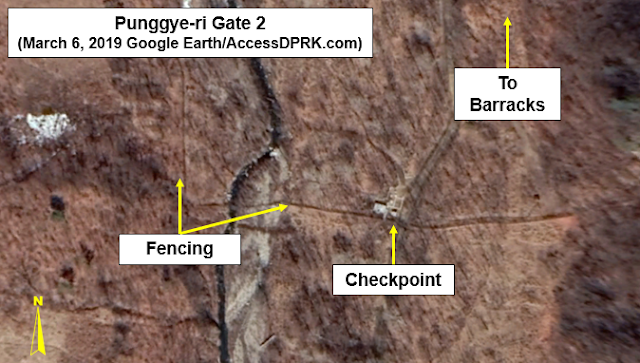

Regardless, warheads may then be taken from Yongdoktong to Punggye-ri for underground nuclear testing or they could be sent to one of a dozen or so ballistic missile bases.

Validating the design of new warheads through testing is an important step in developing a credible nuclear force, particularly as North Korea advanced from testing crude nuclear devices (as in 2006) to developing miniaturized thermonuclear devices that could be mounted onto missiles.

It is likely that further testing will be required as North Korea refines its designs and develops new variants. Currently, it is generally accepted that North Korea now possess ~30 operational nuclear warheads and is actively building more.

Ballistic missiles require adequate device miniaturization and heat shielding to deliver a functional warhead to the target. U.S. intelligence assessments concluded that North Korea had developed the capability to miniaturize a nuclear device and mount it onto a ballistic missile by 2017.

However, there is still debate whether or not Pyongyang has yet developed the capability to manufacture the necessary heat shielding for the reentry vehicles that are used in hypersonic missiles and MIRVs (multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles) that North Korea's seeking to acquire.

The country has around a dozen operational ballistic missile bases and a further dozen or so support facilities (for equipment storage, training, etc.). These bases are roughly divided into three "belts" around the country, with medium-to-intermediate range ballistic missiles and intercontinental ballistic missiles being deployed at bases in the "operational" and "strategic" belts (in the center and northern parts of the country respectively), and short-range missiles deployed in the "tactical" belt close to the DMZ.

There are questions whether or not any warheads are actually stored at these missile bases, ready to be launched, or if they are all held at Yongdoktong and would only be moved to missile bases following a direct order from Kim Jong-un.

Keeping them at Yongdoktong would introduce a serious delay in North Korea's ability to rapidly launch a nuclear-armed missile as the warheads would have to be transported from there to the bases. (The nearest operational base to Yongdoktong is over 50 km away by road.)

But for now, any discussions about deployed warheads or North Korea's nuclear command and control remains largely speculative.

What isn't speculative is that North Korea has worked for decades to develop the technology and infrastructure needed to build a nuclear arsenal, despite international condemnation and despite the tremendous hardships the nuclear program has caused the people of North Korea.

And although I was able to highlight several publicly known nuclear facilities in this article, North Korea is known to have other undeclared research and industrial centers that play a role in the country's nuclear weapons program. Having a detailed accounting of these sites will be imperative to any successful denuclearization or arms limitations agreement in the future.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters who help make all of this possible: Alex Kleinman, Amanda Oh, Donald Pierce, Dylan D, Joe Bishop-Henchman, Jonathan J, Joel Parish, John Pike, JuneBug, Kbechs87, Nate Odenkirk, Russ Johnson, and Squadfan.