Phase II of the #AccessDPRK Mapping Project was published on March 5, 2017, but simply knowing where everything is doesn't make understanding the full picture much easier - especially when considering there's over 50,000 places marked. So I've put together these basic charts showing the total number of items per division (monuments, military, and domestic), the total items per province, and the total number of items within each type mapped (AAA sites, elite compounds, dams, communication centers, schools, etc.).

I'd like to point out that the overall figures here will differ slightly form the ones listed in the March 5th publication article. All told, there are some 600 individual sub-folders I have to keep track of and the resulting numbers take up 24 pages; minor mistakes happen. A couple numbers were inverted, and a few others were slightly off, however the overall discrepancies are very minor when compared with the whole. After making those needed corrections, the information below should be considered as authoritative as it will get with regards to the project.

The following charts (monuments, military, and domestic) represents the most detailed map of North Korea ever released to the public.

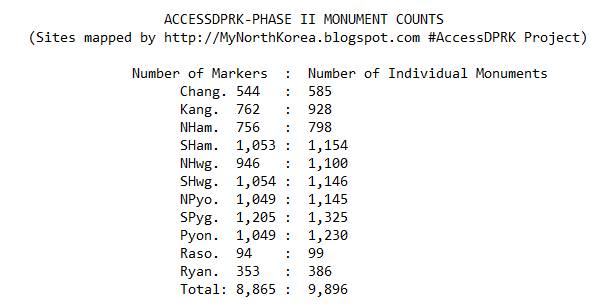

Many monuments are clustered closely together, making marking each one individually impractical. Instead, some markers are placed next to a group of monuments (2-4 generally), so while Pyongyang may have 1,049 markers on the map, those markers represent 1,230 individual monuments.

It's important to note, for those unfamiliar with the project, that the numbers below represent the numbers within the various folders by those names. There will be some items where there will only be one or two places within a province - those didn't necessitate their own folders. In such cases, they're often located in the "un-categorized" folder. An example of this is military training centers and military factories. Just about every province has at least one, but only a few have a folder dedicated to them. A similar situation exists within the domestic file; bunkers, water towers, jails, and others may or may not have their own folder, but they will all be mapped.

While the purpose of this project is to map every one of a particular item, there are some items that I did not intend on mapping each and every one of, such as "firing positions". These trenches and prepared (but empty) gun positions cover the country and number in the thousands. In many cases it's also difficult to determine whether or not something was just a leftover temporary fortification from the Korean War or is part of the country's current defense structure (which does include having trenches in just about every available space). Additionally, the "radar" count is predominantly stand-alone radar sites, not the numerous smaller radars that accompany permanent artillery positions; although some of those are mapped as well. "Gates" are only mapped when they help define the boundaries of an area or are large - there's no real need to map every single gate at every single military site.

With the exception of a few items: canals, signs, factories and farming (to a degree), mountaintop sites, gates, and water supply, I have tried to be as comprehensive as possible in mapping each and every one of the other sites. Regarding the number of factories and farming/agricultural facilities, I focused on only mapping the larger sites, while also mapping some smaller agricultural facilities (like wheat threshing sites) to provide examples of what those numerous places look like.

In short, the map contains 8,865 monument markers (representing 9,896 individual monuments), 9,594 military sites, and 35,252 domestic and economic sites for a total of 53,711 placemarks. There are also hundreds of fences and other things outlined in the map, but those aren't included in the counts as the places fenced in have already been accounted for.

#AccessDPRK will occasionally be updated to provide greater accuracy as new information comes in, fixing any unintentional errors, and adding more details.

--Jacob Bogle 7/4/17

JacobBogle.com

Facebook.com/JacobBogle

Twitter.com/JacobBogle