One such current mega project is the Tanchon Hydroelectric Power Station.

Despite being named for the coastal city of Tanchon, the project centers around the border area between Ryanggang and South Hamgyong provinces, specifically around the worker's district of Sinhung, 53 km away from Tanchon as the crow flies. However, this isn't a run-of-the-mill hydroelectric dam. It is a massive complex that starts at a new water intake point at the Samsu Reservoir (near Hyesan) and then carries water through a roughly 60 km-long tunnel to the electricity generating stations in Sinhung. The tunnel is the longest such tunnel in the country and makes this the largest hydroelectric project currently underway by North Korea.

The next longest water tunnel for hydroelectricity that I am aware of is the Songwon Dam tunnel. Constructed in 1987, it runs a mere 42 km.

The Tanchon project is actually part of a larger attempt to take advantage of the rivers and steep valleys of this region. The northerly-flowing Hochon River is the primary source of water. The northern extreme is the Samsu Dam and reservoir, which lie less than 10 km from Hyesan and the Yalu River border with China (into which the Hochon empties).

In this complicated image you can see the path of the Hochon River (blue), flowing south to north. That water fills the Samsu Reservoir where the water intake site is located for the Tanchon project. That water is then diverted through a tunnel (white) where it travels north to south (against the natural gradient of the area). It will then enter the dual Tanchon generating stations in the small town of Sinhung. From there, it empties into the Namdeachon River (yellow) which flows north to south and empties into the sea at the city of Tanchon.

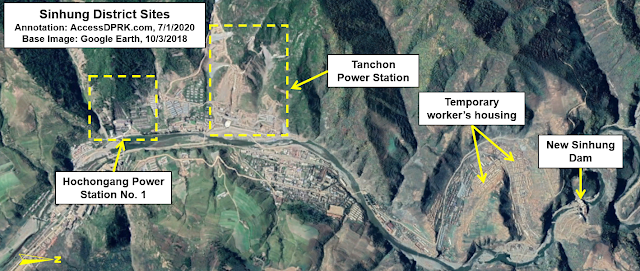

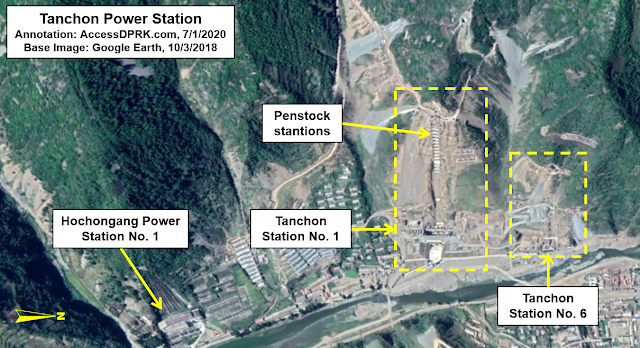

Moving south (aka upriver), lies the Sachophonyg Reservoir which feeds the Hochongang Power Station in Sinhung (11.8 km away and is adjacent to the new Tanchon generating stations). Both the Hochongang Power Station and the new Tanchon stations empties the waters of the Hochon River into the Namdaechon River, across a sort of continental divide thanks to the tunnels, as the Namdaechon then runs south and empties into the Sea of Japan, whereas the headwaters of the Hochon arise in the Hamgyong Mountains (also known as Gangbaekjeonggan) which create a natural border between Ryanggang and South Hamgyong provinces.

Being built at the same time as Tanchon is a smaller hydroelectric dam on the Hochon at Saphyong-ri (pictured above) and a hydroelectric dam at Sinhung (also called Power Station No. 5) on the Namdaechon River that is less than 2 km from the new Tanchon generating station.

Exploiting this riverine resource goes back nearly a century. During the Japanese occupation era, Yutaka Kubota (founder of the Japanese engineering firm Nippon Koei) was a consultant for the Hochongang River Overall Project from 1925-45, and the project was expected to eventually generate 338 MW of electricity.

Samsu Dam ca. 2011. The large propaganda sign in the background reads "Long live Songun Korea's General Kim Jong Un!" and is over half a kilometer long. Image source: Wikimapia.

In terms of North Korean efforts, the Samsu Hydroelectric Dam alone was supposed to produce 50 MW of electricity to provide for Ryanggang Province and the important Hyesan Youth Copper Mine. Built from 2004-2007, the dam was beset with problems and still fails to live up to expectations.

Kim Il Sung introduced the modern idea of exploiting the rivers in the area in the years soon before his death and wanted the project to generate 400-500 MW. But it wasn't until 2016 when Kim Jong Un announced the construction of the Tanchon Power Station that work finally began. According to a May 2017 Pyongyang Times report, the project is supposed to generate "several hundred thousand of kilowatts" and would indeed be the largest hydroelectric project in the country's history.

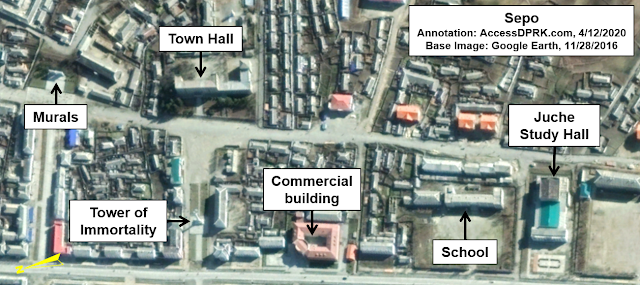

During Kim Jong Un's 2016 New Years' address he said, "The problem of electricity should be resolved as an undertaking involving the whole Party and the whole state." Giving little detail about the project he went on to say, "The construction of the Tanchon Power Station and other projects for boosting the country’s power-generating capacity should be promoted along with the efforts to ease the strain on electricity supply by making proactive use of natural energy."

Such an undertaking would indeed require the effort of the "whole state".

As discussed in the Songwon article, one reason to not locate the electric generating station at the site of a dam or to excavate miles of tunnels to divert water elsewhere, is to take advantage of a substantial change in elevation. The greater the difference between the elevation of where the water is stored (in this case the Samsu Reservoir) and where it runs through the turbines at the generating station, the greater the power generated.

The approximate elevation of the water intake site at Samsu is 2,500 ft above sea level. The tunnel cuts through mountains and valleys on a downhill gradient to deliver the water to a point roughly 1,800 feet above sea level. This represents a 700-foot drop, something no existing traditional hydroelectric dam in the country could provide. For some perspective, to otherwise maintain a hydraulic head of 700 feet would require a traditional dam on the scale of the Glen Canyon Dam in the United States.

The elevation drop also allows a relatively small amount of water to pick up momentum and hit the generating turbines with more energy, producing more electricity. Both the Songwon and Samsu water intake sites are placed at shallow ends of their respective reservoirs, meaning limited amounts of water can transit the tunnel system. This may seem counter intuitive, to only have a little water flowing through, but considering the number of droughts North Korea has, it could also allow for a more constant supply of electricity (albeit limited) but without draining the reservoirs or damaging the tunnels over time.

Despite all the work visible via satellite images, by March 2020 the project was only fifty-percent completed. On April 17 the regime announced that the number of "national projects" would be cut from 15 to 5 projects. One such project is the new Pyongyang General Hospital and it is consuming substantial resources from across the country.

However, according to the Pyongyang Times, by June construction was being "pushed dramatically" and key parts of the project are now nearing their "final stage". This jump in activity is a common theme among North Korean projects and suggests that Tanchon is one of those five main national projects still being given priority as their economy struggles due to COVID-19 measures and ongoing sanctions.

Once completed, Tanchon would be the culmination of generations of planning and levels of backbreaking work rarely seen in today's modern world.

The 60-kilometer tunnel was built by cutting dozens (over 50) of individual access tunnels into solid rock to slowly expand and lengthen the main water tunnel. North Korea lacks tunnel boring machines, so the work is being done with small excavation equipment and by hand.

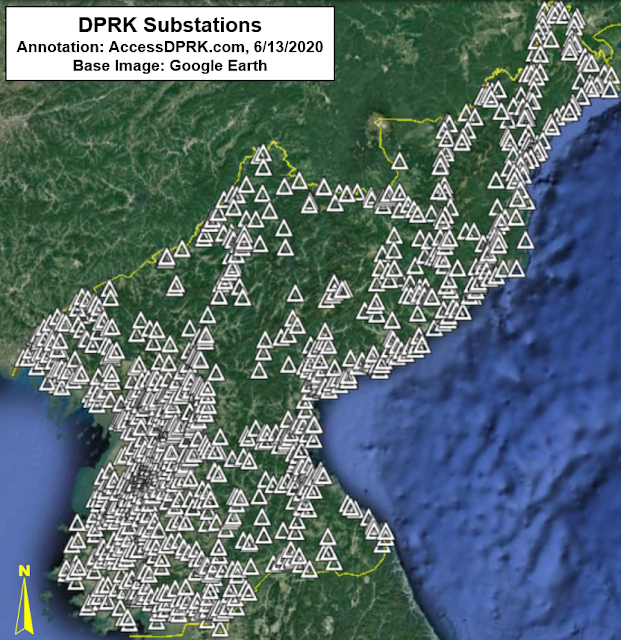

The construction of the generating station will consume thousands of tons of concrete and steel, and its power distribution lines will run for untold miles connecting the site to the national energy grid.

Unfortunately, any projections that Tanchon will substantively ease regional energy needs should be taken with a grain of salt. As mentioned, Samsu Dam has failed to generate electricity at its designed capacity and other dams have likewise suffered from setbacks. Even the backbone of North Korea's energy grid like the Pyongyang and Pukchang thermal power plants are constantly plagued by generation and efficiency problems, and blackouts in Pyongyang itself are still a common occurrence.

However, if Tanchon does live up to the majority of expectations, it and the other hydroelectric stations along Hochon's 220 kilometers will finally surpass the planned generating capacity by the Japanese all those many years ago.

Additional reading:

38 North has been covering the construction progress of the Tanchon project. You can read their detailed work here and here. Also, see AccessDPRK's November 2020 update.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters: Amanda O., Anders O., GreatPoppo, Kbechs87, Planefag, Russ Johnson, and Travis Murdock.

--Jacob Bogle, 7/2/2020

AccessDPRK.com

JacobBogle.com

Facebook.com/accessdprk

Twitter.com/JacobBogle