In the earlier days of AccessDPRK, I wrote a short brief on urban warfare training centers around North Korea, otherwise known as military operations in urban terrain (MOUT). This was before the first full version of the AccessDPRK map was completed and after nine years, new discoveries have been made, and new facilities have also been constructed.

With North Korean soldiers now in Russia, likely facing new urban combat situations in the weeks to come, I wanted to take the opportunity to revisit the topic and provide some updates to the earlier article.

To review, the United States Marine Corps defines MOUT as "all military actions planned and conducted on a topographical complex and its adjacent terrain where manmade construction is the dominant feature. It includes combat in cities, which is that portion of MOUT involving house-to-house and street-by-street fighting in towns and cities".

It is believed that North Korea's primary goal during a renewed invasion of South Korea will be the capture and holding of Seoul, a city with a core population of over 9 million and a metropolitan population of 26 million. To achieve that objective, North Korean special operations forces will need to infiltrate behind the South's defensive lines at the DMZ and begin to isolate Seoul and its surrounding population centers from the rest of ROK and US forces, enabling the main body of the Korean People's Army to move in and take the city.

Indeed, according to the United States Army, the first moves of the KPA Ground Forces "will likely isolate the bypassed cities to prevent assistance from the outside or a breakout from inside the urban area."

Naturally, one needs to know how to engage in combat within populated areas to accomplish that.

Urban warfare is one of limited movement; fighting not just street-to-street but within buildings floor-to-floor, and it can require a multi-domain battle approach (land, air, and even sea) that, all too often, results in very high casualty rates. And so, getting proper training for the urban environment is essential.

In total, I've been able to identify fourteen MOUT facilities across North Korea.

Four of them are much larger than any of the others and three are dedicated to training against specific, real-world targets: the Panmunjom "Truce Village", the ROK Armed Forces headquarters at Gyeryongdae, and there is also a mockup of the Blue House - the South Korean presidential residence until 2022.

The other sites are smaller and fairly non-descript, but they often retain hints of the 1960s and 1970s South Korean architectural style that the larger MOUT facilities were constructed to simulate back when they were first established.

There is also an alleged underground facility in Pyongyang that contains a scale model of a 'typical' district in Seoul complete with functional buildings and even "employees" who help the special forces personnel engage in conversation, use South Korean won, and otherwise help them become acclimatized to South Korean culture so that they can better infiltrate the South. However, its existence and location haven't been independently verified.

Main Facilities

The largest MOUT facility (40.014045° 125.885854°) in North Korea is located in Unsan County near the village of Majang-ri. The army-level base, with all of its associated facilities, covers more than one square kilometer and includes an airborne drop tower that was built in 2014. But the MOUT part of the base covers 62 hectares and it is divided into three main sections.

The first section includes the base's headquarters, barracks, and associated buildings. The second section is the "urban terrain" which is 25 hectares and includes around 80 mock structures between one and six floors high. And the third section is a smaller MOUT complex that was added ca. 2014-16 and has mock satellite dishes and communication facilities.

The second largest MOUT facility in the country is Soe-gol in Pyongyang (39.080629° 126.092776°). Soe-gol is a large training complex with a MOUT facility, tank training areas, and other facilities. I wrote about the overall complex in 2019, following a major expansion of the base.

The MOUT facility has also undergone expansion over time. In 2005 there were twelve structures and by 2011 there were 47. There have been some small changes to the structures since 2011, but the total number remains about the same.

On the outskirts of Pyongyang is another MOUT facility (38.967371° 126.105667°), about 4 km east of the village of Pakkoryong. Positioned within a small valley on the banks of the Nam River, it's fairly isolated and doesn't even have a paved road leading to it. But the Kim Jong Suk Military Academy is in Pakkoryong, and so the MOUT facility could be operated by that institution.

Established in the late 1980s, it occupies about 22 hectares and is aligned on an east-west axis. The easternmost section contains the base's headquarters and barracks. Then there's a 200-meter-long "road" with mock buildings on either side. At the west end there are eleven greenhouses that were built in 2019.

There are other structures dotted around the hillsides for a total of approximately 30 mock buildings.

The last of the large MOUT facilities is in Pyongsan (38.400285° 126.370334°). It's part of the KPA Army II Corps headquarters, which is nearest to the village of Wahyeon-ri (와현리) and is 57 km from the DMZ.

The MOUT section and associated support buildings only take up 3.3 hectares and extends for 190 meters. Unlike other MOUT facilities, the Pyongsan location has actually shrunk in size over time. In 2011 it spanned over 6 hectares and was 340 meters in length. Some of the smaller structures were razed ca. 2012 and it was further reduced in size when an airborne training drop tower was constructed nearby in 2015-17.

Currently, 15+ different facades and mock buildings make up the MOUT facility.

Replica Facilities

Panmunjom is the village that used to straddle the border between North and South Korea, and it is where the 1953 Armistice Agreement was signed. It plays a highly symbolic role on the Korean Peninsula and is now where the Joint Security Area is located, which hosts inter-Korean talks, is a tourist hotspot, and has even witnessed several defections over the years as North Koreans dash across the Military Demarcation Line into the South.

In late 2017, a replica of Panmunjom was constructed 17 km east-northeast of the real Panmunjom, just on the other side of Kaesong. Coincidently, on Nov. 13, 2017, just a few months after the completion of the replica, a North Korean soldier defected by crossing the DMZ at the real Panmunjom.

The replica facility was built on the site of a pre-existing military base and includes a fairly accurate (though, not precise) replica of the major Panmunjom buildings: the large Freedom House, the seven "blue huts" of the Armistice Commission buildings, and facades of the Peace House and Panmun-gak Administrative Headquarters.

Security hut models and a replica DMZ post were also constructed on the site.

The exact reason for its construction isn't known, but apart from its usefulness in training special operations forces to infiltrate or seize the site, it may have been used to help familiarize DPRK personnel with Panmunjom prior to the 2018 meetings between Kim Jong Un and South Korean president Moon Jae-in, as well as for the 2019 meeting between Kim and US President Donald Trump.

Gyeryongdae is the Republic of Korea Armed Forces Headquarters located at 36.308581° 127.218556°, about 136 km south of Seoul. The octagonal, tri-service building was constructed from 1985-89.

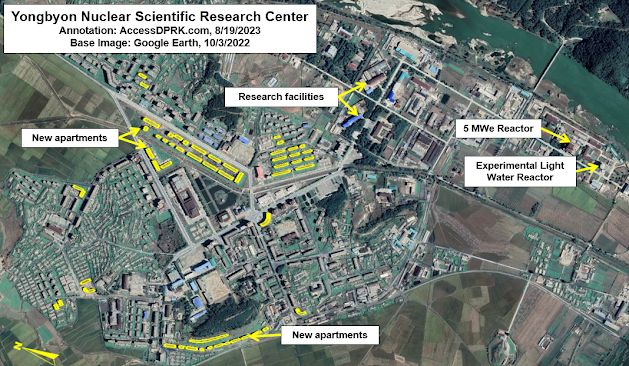

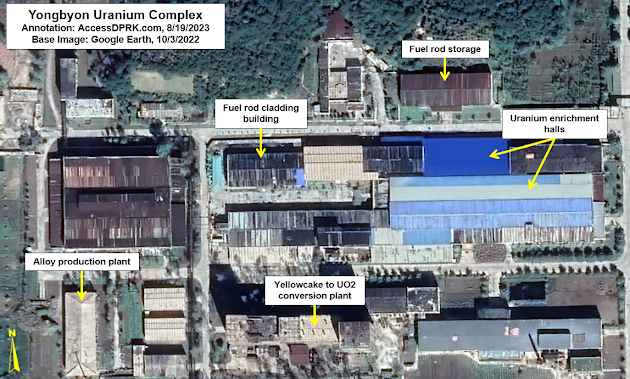

Given its location in the interior of the country, it's doubtful that any DPRK soldiers could make it that far before being stopped by ROK and US allied forces. Nonetheless, in 2017-18, North Korea built a 1/4th scale model of the building at a training base (39.849323° 125.681858°) just 8 km northwest of the Yongbyon Scientific Nuclear Research Center in the village of Gusan-ri.

Each of the building's eight sides are 15 meters long and the building is 40 meters in diameter. Imagery is limited, but it does look like they tried to replicate (in quarter scale) Gyeryongdae's height as well.

Unlike the Blue House replica (discussed below), I'm not aware of any military exercises at the Gusan-ri site that have been made public.

In April 2016, North Korea built a replica of the Blue House, which was the official residence of the president of South Korea between 1948 and 2022. North Korea launched a raid on the real Blue House in 1968 in an attempt to assassinate South Korean president Park Chung Hee. The attack failed but not before 59 people died (29 North Koreans, 26 South Koreans, and 4 US servicemembers).

In preparation for the 1968 raid, members of the KPA special forces Unit 124 trained at their own replica of the building. Forty-eight years later, a new mockup was constructed on the outskirts of Pyongyang at 38.928852° 125.924206°.

The range of hills where the replica is constructed has been used for military exercises for many years, and there is even an executive observation facility 3 km north (38.947974° 125.915933°) that was built in 1996, where the Kims and military leaders can watch the exercises when they want.

Since the replica's construction, North Korea has conducted at least two "raids" on the structure and publicized them through official state media. Following these drills, the structure has been left in a nearly totally destroyed state.

Additional MOUT Facilities

There are at least seven additional MOUT facilities around the country of various sizes.

1. Haeju-Sinchang (38.134321° 125.751458°) is a set of four, multi-floor structures built in 2011 that are part of a much larger training base. It is located in the mountains 10 km north of Haeju.

2. Fifteen km northwest of the Haeju base is the Kyenam MOUT facility (38.207401° 125.604108°). The area was just a rural agricultural area until 2017-18 when various military buildings were constructed. A compact MOUT facility covering 3 hectares was also built. It had 19 small structures inside the fenced perimeter in 2018. But by 2021, the fence appears to have been removed, three of the structures were converted into real houses, and the other MOUT structures have been left to decay.

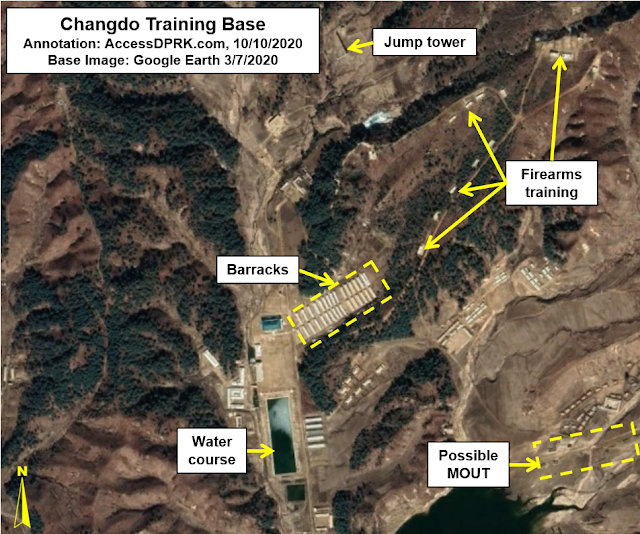

3. Near Changdo, Kangwon Province is a large training complex. An apparent MOUT section (38.641828° 127.753018°) was built in 2018-19 consisting of ten, single-story structures. A large number of barracks were also constructed at the same time, some 430 meters away, as part of renovations to the wider base.

4. A possible MOUT facility (38.553567° 124.994947°) was constructed in 2018 at a base 4 km south of the Pip'a-got submarine base. It doesn't look like the traditional mock buildings but may be collection of facades (single walls) used for targets.

5. In Pyongyang, 4.5 km northeast from Kim Jong-un's house, a set of 4 MOUT structures were built between 2009 and 2011. The coordinates are 39.148852° 125.851172°

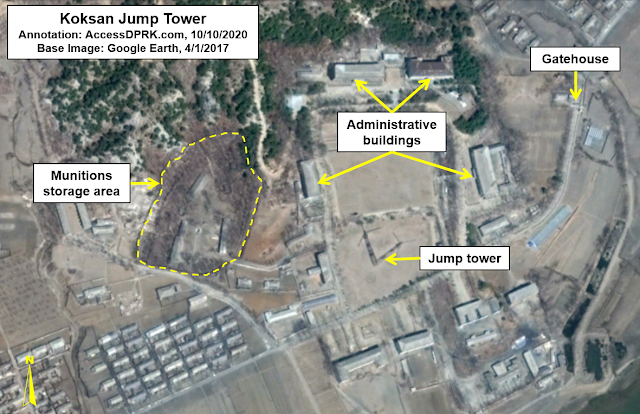

6 and 7. The area around the Chik-tong Airfield in Koksan has two MOUT facilities. The northern one (38.723600° 126.693819°) is a modest site built in 2019. The southern facility (38.709796° 126.670334°) is larger with at least 27 structures and was constructed in 2020. Koksan has been reported to be one at which KPA soldiers bound for Ukraine have trained.

Similar MOUT training centers in countries like the United States are known to change every few years and present different urban environments that national forces may confront. After all, a city in Iraq is going to have different requirements than one in Siberia or in eastern Europe. But North Korean MOUT "villages" rarely change and are largely stuck in their design and reflect a doctrine that developed in the 1970s.

And although the KPA's presence in Russia and Ukraine is giving North Korean soldiers the first experience of combat almost any of them will have ever seen, fighting among the towns of the vast Central Russian Plateau is only partially instructive for fighting in a dense urban environment with skyscrapers and a complex underground transit system - a city vastly changed from the Seoul of the 1970s.

Nonetheless, particularly as it pertains to small unit tactics, North Korea's MOUT facilities still offer a fertile environment for the introduction to urban combat and to the skills needed to minimize the risks associated with fighting in a populated area.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters who help make AccessDPRK possible: Donald Pearce, David M., Dylan D, Joe Bishop-Henchman, Joel Parish, John Pike, Jonathan J., Kbechs87, Raymond Ha, Russ Johnson, Squadfan, and Yong H.