On August 8, 2019 I wrote a post about highly visible leaks at the Pyongsan Uranium Mine and Milling Factory. In the post are satellite images that clearly show waste leaking going back to at least 2003.

Despite the other things that I have been able to show through the #AccessDPRK project, this particular one caught the attention of the international media. Before long I was being contacted by Radio Free Asia and then UPI picked it up, followed by Chosun Ilbo, UK tabloids, and even state sponsored sites like Sputnik News. Some contacted me directly while others brought in their own experts to do the analysis. Almost all of these additional experts agreed that pollution of any kind from the plant would be cause for concern.

However, all of this attention also meant that people started asking other questions and needing clarification. Some, it seems, have even tried to deliberately distort what it is I actually said to fit their own narrative. I want to take this time to clear a few things up and to offer additional support for what I have said.

First, my original post is titled "Radioactive River" because it is about a uranium facility polluting a river. In that post I only talked about pollution in general terms saying, "the pipe taking waste materials to the open reservoir has leaks and has been spilling toxic water into the Ryesong's tributary". I said that the Ryesong is the main water source for 200,000. (However, if you widen the area to include a few extra miles on either side of the river, that figure doubles to 400,000.)

The first interview I had was with Radio Free Asia. The three minute phone call consisted of very few questions. One of the questions asked was if the waste material could be radioactive. I said yes, that some of the material could be. That one answer seems to be what most people are concerned about and confused over.

North Korea uses low-grade coal as the uranium source. Pyongsan's coal has 0.26% uranium concentration. Apart from that, lower grade coal also contains lead, arsenic, vanadium, cobalt, and other heavy metals as well as small amounts of additional radioactive material. Processing and burning coal leaves behind radioactive waste. A 2007 Scientific American article put it succinctly, "coal ash is more radioactive than nuclear waste". This is because burning it concentrates the impurities already existing within the coal. But the coal always had those materials inside of it, regardless of burning. The coal is still not pure. Whether it is burnt, crushed, or just dumped into a river, it is not a safe material to be placing into a water supply

The black sludge seen at the Pyongsan reservoir is the leftover coal from the plant along with residual acids and other industrial products. It is moved from the plant in slurry form and emptied into the reservoir. During that movement, some leaks out of cracks in the pipe and ends up contaminating the Ryesong River which then eventually flows into the Han River estuary.

Regardless of the inherent dangers of leaking coal slurry, uranium mining and milling (the process of turning uranium ore into yellowcake) creates its own radioactive waste.

According to the EPA, "regardless of how uranium is extracted from rock, the processes leave behind radioactive waste....The tailings remain radioactive and contain hazardous chemicals from the recovery process."

The key to making the process safe is proper handling and storage of the waste products. North Korea is not a member of the International Labour Organization which plays a major role creating safety rules for those that work around radioactive materials. Additionally, there is no evidence that the reservoir is lined. Lining the reservoir is an extremely important part of ensuring that the toxic water doesn't leak into rivers and groundwater. The fact it is unlined was mentioned by Dr. Jeffrey Lewis, the director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Program at the Center for Nonproliferation Studies. Dr. Lewis stressed on his website the negative health concerns associated with dumping the material into an unlined pond saying, "What is definitely happening, though, is that North Korea is dumping the tailings from the plant into an unlined pond, one surrounded by farms. That’s not a hypothetical harm. That’s actual pollution that is harming the health and well being of the local community."

The facts are beyond dispute, and regardless of the exact amount of radioactive material being spilled into the river, there are also large amounts of other dangerous chemicals that are leaking out: the aforementioned lead, arsenic, vanadium, mercury, and others. All of those things cause health problems and there is no "safe limit" to lead and arsenic ingestion.

Aside from the leaking material, even the waste within the reservoir poses a risk. During periods of dry weather, the surface of the sludge pile can dry out. Wind can pick up those small particles and carry them for miles, depositing them on land, homes, and within the lungs of anyone breathing it.

Pyongsan doesn't exist in a vacuum, either. Defector testimony from those who have worked in North Korea's nuclear program (either as miners, technicians, scientists, etc.) or simply lived in areas around nuclear sites have pointed to ongoing heath problems and birth defects. Recent defectors have even shown evidence of radiation exposure because they lived downwind of North Korea's Punggye-ri nuclear test site. The people downriver of Pyongsan aren't immune to pollution.

I am not trying to be alarmist. This is not Chernobyl or Fukushima, but all of this provides strong evidence that there is an ongoing health crisis in this part of North Korea and that some of the toxic materials being dumped into the Ryesong will inevitably reach the Han River.

I am not a nuclear weapons expert. I have never claimed to be. I am a concerned individual who has spent the last seven years of his life studying North Korea and bringing attention to important issues. I am not getting paid by any government or partisan organization. And while I don't know what constitutes being an "expert" to some, my years of work speaks for itself. I created a map with 53,000 locations, I was the first to report on a new test site at the Tonghae Satellite Launch Station, I have multiple reports on the growth of North Korea's military, I created a survey of the country's archaeological sites using open-source satellite imagery, and I was the first to report on the replica of Panmunjom. I think that qualifies me to say that black industrial waste flowing into a river is a bad thing.

Evidence of widespread contamination from various nuclear-related facilities exist around the world. And continuing fears over Fukushima and the recent accidents in Russia mean that we must all be vigilant. For my part, I will continue to observe every square mile of North Korea and to report on the things I find.

--Jacob Bogle, 8/24/2019

Patreon.com/accessdprk

www.JacobBogle.com

Facebook.com/JacobBogle

Twitter.com/JacobBogle

The AccessDPRK blog is dedicated to exposing North Korea via satellite imagery. Discussing domestic, economic and military locations and helping to uncover this hermit kingdom.

Saturday, August 24, 2019

Wednesday, August 21, 2019

Slowdown at the Pakchon Uranium Plant?

In the course of researching my article on the toxic leaks at the Pyongsan uranium mine and milling plant, I started observing North Korea's second such facility at Pakchon, North Pyongyan.

Reviewing historical satellite imagery for Pyongsan shows an ever-growing pile of tailings (waste material) and sludge from the mine and factory at its waste reservoir, indicating continual operations. The same cannot be said upon review of the reservoir at Pakchon. A lack of obvious changes to the reservoir recently could mean a few things, which I'll discuss later.

Like Pyongsan, Pakchon was constructed in the 1980s under the leadership of Kim Il Sung (with various degrees of Soviet assistance), and is the second of North Korea's two declared uranium milling plants (where uranium ore is processed into yellowcake). The other plant being Pyongsan, as mentioned earlier. A review of satellite imagery shows the evolution of the Pakchon facility's operations.

Google Earth imagery from 2005 shows that the original tailings dam had been closed and turned into farmland, while a second tailings dam had been established during the intervening years.

By 2014, activity at the dam can still be seen, as new materials are dumped into it via truck (unlike the reservoir at Pyongsan, which has waste material moved via pipe).

The addition of new waste to the dam appears to have slowed down by 2016.

The small sections of the reservoir that were active in 2014 no longer seem to be undergoing change, and there isn't much (if any) additional activity as evidenced by the lack of surface disturbances.

The general lack of new waste deposits has continued into 2019. Any changes to the reservoir from 2016 and 2019 are very minimal, indicating a lack of production. By comparison, the growth of the "sludge pile" within the Pyongsan tailings reservoir grew substantially.

The Pyongsan plant is much larger than Pakchon and processes coal with a uranium concentration of 0.26%, compared to Pakchon's 0.086%. Both are considerably low-quality concentrations by most definitions but seem to be among the best ore the country has domestic access to.

The sludge pile within the Pyongsan reservoir occupied some 69,000 square meters of space by May 2017.

The pile had grown to approximately 87,000 square meters by March 2019, an apparent increase of 26%. An exact figure can be difficult to ascertain because water levels may have changed slightly over time.

The only area of Pakchon that seems to have maintained activity is the associated mine, 1.3 km south of the main factory building.

Aside from monitoring tailings, the physical state of the factory complex gives us more information.

The main building is roughly 120x100 meters, but there are several other buildings involved in the process of concentrating and milling the uranium. The administration section of the complex seems perfectly fine, but two industrial buildings are falling apart, and one of those is in the process of being demolished.

Google Earth imagery from March 19, 2012 gives a clear view of the two buildings of interest. They are in good order and appear functional.

By March 2019, the roof of building #1 has several holes in it and building #2 has been torn down.

What does all of this mean?

It would make sense that Pyongsan would be the country's primary facility, as the ore used is of much greater quality than the ore at Pakchon. Indeed, Pyongsan underwent a refurbishment in 2014-2015, with additional improvements being seen even more recently. But is Pakchon slowing down?

A lack of obvious waste deposits and the fact that some of the buildings have been neglected or demolished points to problems. Mining operations have continued, but there doesn't seem to be a new tailings dam that would explain the lack of activity at the current one. The mine has settling/separation ponds but doesn't appear to have a dedicated spot to hold waste from the processed material. This could indicate that the country is stockpiling material for processing but has cut back on the overall amount of milled uranium it can produce at Pakchon. This may be backed up by the fact that, at least for 2019, even work conducted at Yongbyon has been scaled back.

Another possibility is that there are problems with the factory itself. North Korea's industrial sector has long been crippled for its lack of spare parts and its general inability to repair and replace complex equipment in a timely fashion. Additionally, uranium processing is expensive and energy intensive. During the early days of North Korea's nuclear program, the Soviet Union told them that it wasn't economically feasible to extract the low-quality uranium sources within the country. Nonetheless, Kim Il Sung persisted. The energy intensive and expensive nature of the process may have finally caught up with them, leading to scaling back Pakchon.

Pakchon has never operated every single day, but this prolonged period with little to no activity is a change from the time under Kim Jong Il. It will take more observations to know exactly what is happening, but for now, Pakchon certainly doesn't seem to be operating at its full capacity.

--Jacob Bogle, 8/21/2019

Patreon.com/accessdprk

www.JacobBogle.com

Facebook.com/JacobBogle

Twitter.com/JacobBogle

Reviewing historical satellite imagery for Pyongsan shows an ever-growing pile of tailings (waste material) and sludge from the mine and factory at its waste reservoir, indicating continual operations. The same cannot be said upon review of the reservoir at Pakchon. A lack of obvious changes to the reservoir recently could mean a few things, which I'll discuss later.

Like Pyongsan, Pakchon was constructed in the 1980s under the leadership of Kim Il Sung (with various degrees of Soviet assistance), and is the second of North Korea's two declared uranium milling plants (where uranium ore is processed into yellowcake). The other plant being Pyongsan, as mentioned earlier. A review of satellite imagery shows the evolution of the Pakchon facility's operations.

Google Earth imagery from 2005 shows that the original tailings dam had been closed and turned into farmland, while a second tailings dam had been established during the intervening years.

By 2014, activity at the dam can still be seen, as new materials are dumped into it via truck (unlike the reservoir at Pyongsan, which has waste material moved via pipe).

The addition of new waste to the dam appears to have slowed down by 2016.

The small sections of the reservoir that were active in 2014 no longer seem to be undergoing change, and there isn't much (if any) additional activity as evidenced by the lack of surface disturbances.

The general lack of new waste deposits has continued into 2019. Any changes to the reservoir from 2016 and 2019 are very minimal, indicating a lack of production. By comparison, the growth of the "sludge pile" within the Pyongsan tailings reservoir grew substantially.

The Pyongsan plant is much larger than Pakchon and processes coal with a uranium concentration of 0.26%, compared to Pakchon's 0.086%. Both are considerably low-quality concentrations by most definitions but seem to be among the best ore the country has domestic access to.

The sludge pile within the Pyongsan reservoir occupied some 69,000 square meters of space by May 2017.

The pile had grown to approximately 87,000 square meters by March 2019, an apparent increase of 26%. An exact figure can be difficult to ascertain because water levels may have changed slightly over time.

The only area of Pakchon that seems to have maintained activity is the associated mine, 1.3 km south of the main factory building.

Aside from monitoring tailings, the physical state of the factory complex gives us more information.

The main building is roughly 120x100 meters, but there are several other buildings involved in the process of concentrating and milling the uranium. The administration section of the complex seems perfectly fine, but two industrial buildings are falling apart, and one of those is in the process of being demolished.

Google Earth imagery from March 19, 2012 gives a clear view of the two buildings of interest. They are in good order and appear functional.

By March 2019, the roof of building #1 has several holes in it and building #2 has been torn down.

What does all of this mean?

It would make sense that Pyongsan would be the country's primary facility, as the ore used is of much greater quality than the ore at Pakchon. Indeed, Pyongsan underwent a refurbishment in 2014-2015, with additional improvements being seen even more recently. But is Pakchon slowing down?

A lack of obvious waste deposits and the fact that some of the buildings have been neglected or demolished points to problems. Mining operations have continued, but there doesn't seem to be a new tailings dam that would explain the lack of activity at the current one. The mine has settling/separation ponds but doesn't appear to have a dedicated spot to hold waste from the processed material. This could indicate that the country is stockpiling material for processing but has cut back on the overall amount of milled uranium it can produce at Pakchon. This may be backed up by the fact that, at least for 2019, even work conducted at Yongbyon has been scaled back.

Another possibility is that there are problems with the factory itself. North Korea's industrial sector has long been crippled for its lack of spare parts and its general inability to repair and replace complex equipment in a timely fashion. Additionally, uranium processing is expensive and energy intensive. During the early days of North Korea's nuclear program, the Soviet Union told them that it wasn't economically feasible to extract the low-quality uranium sources within the country. Nonetheless, Kim Il Sung persisted. The energy intensive and expensive nature of the process may have finally caught up with them, leading to scaling back Pakchon.

Pakchon has never operated every single day, but this prolonged period with little to no activity is a change from the time under Kim Jong Il. It will take more observations to know exactly what is happening, but for now, Pakchon certainly doesn't seem to be operating at its full capacity.

--Jacob Bogle, 8/21/2019

Patreon.com/accessdprk

www.JacobBogle.com

Facebook.com/JacobBogle

Twitter.com/JacobBogle

Saturday, August 17, 2019

Support AccessDPRK Using Patreon

I began mapping North Korea in 2012 as a hobby. Since then, it has turned into an enormous project that has resulted in several important outcomes. Phase II of the national map became the most comprehensive map of North Korea freely available to the public. I was the first to report on a new missile test site at Tonghae, showed that the country has multiple stealth ships, released a data set of over 300 ancient sites in the country, and information from the project has been used to support RAND Corp. reports and others. And most recently, my post showing leaks of polluted material into the Ryesong river from the Pyongsan uranium plant is being discussed by Radio Free Asia, UPI, and others.

Unlike the bulk of North Korea analysts, I'm not part of a think tank with million-dollar grants or part of major news organizations. Everything I produce was created by my own efforts, drawing on years of experience and my library of over 21,000 pages worth of material. However, it does take a lot of time and energy. Getting new research material, accessing subscription-based sources, needing the occasional updated satellite image from companies like Planet Labs...it all takes money.

If you appreciate the work I do and would like to help support me in this endeavor, I'd like to ask for your patronage via Patreon.

Currently there are three levels of support, $3, $5, and $15. Each level comes with additional benefits, like receiving copies of articles 24 hours before the general public and being listed as a supporter on those articles (as well as "thank you" tweets).

I am also working on additional tiers ($20+) and rewards, such as granting access to exclusive data sets, which will be made available in the future.

Please consider helping AccessDPRK keep producing unique and relevant content that opens up the Hermit Kingdom to the world. I will greatly appreciate every drop of support.

The direct link is https://www.patreon.com/accessdprk

--Jacob Bogle, 8/17/2019

www.JacobBogle.com

Facebook.com/JacobBogle

Twitter.com/JacobBogle

Sunday, August 11, 2019

In Defense of North Korea Travel

In September 2017, the US prohibited American citizens from traveling to North Korea (except under special circumstances). This move was ostensibly in retaliation for the horrific and mysterious circumstances surrounding the death of Otto Warmbier. Then in August 2019, the US State Department announced that foreigners who visited North Korea at any time since March 1, 2011 would no longer be able to qualify for visa-free travel to the United States. This newest restriction applies to several other countries as well, but it will make visiting North Korea an even more difficult decision for foreigners who also have family or business in the US.

The argument against visiting North Korea (or any dictatorial country like, Cuba, China, Russia during the days of the USSR, etc.) is that a person is giving money to these repressive regimes and that travel may even be a tacit sign of support. That the money raised by tourism isn't used to bolster their economies or help employees, but goes towards things like weapons programs. The other argument is that it's just too dangerous, especially for Americans.

If you couldn't tell from the title, I reject the idea that the risks of tourism outweigh the benefits. For one, on a purely philosophical level, I believe that every human being has an inherent right to travel anywhere they want to. (Even if the target country doesn't care about human rights.)

As far as safety risks, anyone visiting any country has to be aware of local laws, especially if they have laws surrounding culture, religion, or the leadership. Plenty of other countries have laws that would seem completely insane through the eyes of an American (like going to prison for insulting a king or dancing with a woman you're not married to), so North Korea isn't unique in having absurd laws. What's unique about North Korea is the extreme and severe consequences of breaking those laws. But in terms of the actual risk level, there have only been 16 Americans arrested in North Korea since 1999. I doubt the same could be said of any nationality visiting the United States.

Tour groups often give lengthy warnings about what not to do, and it should be common sense by now to avoid political and religious discussions, to listen to your minders, and to be as respectful as possible. North Korea is a serious place with serious consequences if you screw up, but statistically, an average tourist doesn't seem to be at much greater risk of being arrested than any other average tourist visiting a place like Saudi Arabia, Thailand, or Iran. In fact, the only group at a higher-than-average risk is ethnic Korean-Americans, particularly those who are Christian.

Getting to terms of economics, only a few hundred Americans visited North Korea each year prior to the ban. The total economic impact on the country from American tourists was likely less than $5 million a year.

If Kim Jong Un is anything like his father in his love for alcohol and parties, that money wouldn't even pay his annual bar tab, let alone be directly responsible for propping up a billion-dollar weapons program nor would it significantly boost spending on luxury items like cars and yachts. Indeed, under Kim Jong Il, the regime spent over $600 million a year just on luxury goods.

North Korea's sources of outside income is vast and includes countless illicit programs. Their cyber theft activity is estimated to have brought in some $2 billion over the years. So I don't buy the argument that the extremely limited American tourism industry to the country was having any significant impact on allowing the country to continue doing what it does.

On the other hand, tourism to the country offers many opportunities that further the goals of democracy and benefits the work of North Korea analysts.

The impacts of cross-cultural engagement can't be underestimated. A couple years ago I had the opportunity to travel to Cuba during the brief window created under the Obama administration (which has since been cut off under the current administration). It was a government approved tour to be sure, but I also got to see a decent amount of reality - not just propaganda. I saw trash in the streets, houses without electricity, and suburban neighborhoods in bad need of repair. I also saw a more managed Cuba with an immaculate downtown, loyal soldiers of the Revolution marching around, and people just trying to live their lives. What I didn't see was goosestepping civilians calling for the death of all Americans. In fact, after everyone got comfortable with each other, the message was pretty clear. Cubans recognize that problems exist and they don't necessarily mind overlooking complicated historical matters if it means having a less antagonistic relationship with the US, so long as both sides can open up and allow the Cubans to finally start moving out of the 1960s thanks to tourism and trade.

Actually getting a change to see the "evil" communist Cubans, Soviets, and North Koreans reveals that they are actually people, just like everyone else. They have their own individual desires no matter how hard the regime tries to subdue them and enforce the "collective-first" ideology. That individuality and their realization that North Korea isn't a paradise on earth, is part of a long and inexorable process that will result in the collapse of the Kim family. It is something that was only made possible by North Koreans seeing other parts of the world like, China and Russia, and from outsiders coming in with their fat bellies, modern fashion, and new technology. Being envious of Levi jeans helped fuel discontent among the Soviet youth and the same thing has been happening in North Korea.

The results of trading, especially with China, has been a flood of outside information flowing into the country. This information (largely in the form of foreign movies and TV shows) is seen as a major threat to the regime. It has broken the spell of the "socialist paradise" while also raising the expectations and dreams of the people. And each time the government fails at meeting those expectations and addressing the people's concerns, even more cracks form between government and citizen. And tourism allows each side to realize that the other is human, too. That Westerners aren't bloodthirsty devils and North Koreans aren't as brainwashed as mass media may lead us to believe.

While I have never been to North Korea, I have read countless accounts, watched a ton of video, and looked at loads of pictures of tourists from multiple countries and during different periods of time. No matter how tightly controlled the visit is, human behavior is universal. Once a level of comfort sets in, people start talking. Sometimes it's just a small amount chatting, but others results in a relative flood of information being quietly exchanged between people. This adds even more fuel to the fire that has severely damaged Pyongyang's ability to blackout information and to squash growing aspirations.

And all of those stories, pictures, and videos help shed light on scores of interesting areas, often inadvertently. They can show new buildings, verify the location of a factory or other place of interest, they show propaganda posters, which allows analysts to get a better grasp of what the government is telling their people (verses what they're telling the world) and where their current interests lie. They can also give us a close look at infrastructure, car and cell phone use, and even more mundane things like current fashions. All of this augments and helps verify what we can learn from defectors and satellite imagery - both of which come with their own problems. If you take away tourism, you take away thousands of new pictures and thousands of hours of video each year. To me, that seems to be the exact opposite of what the West has been trying to do: reveal as much as possible about a country run by dangerous people with nuclear weapons.

--Jacob Bogle, 8/11/2019

www.JacobBogle.com

Facebook.com/JacobBogle

Twitter.com/JacobBogle

Labels:

opinion,

Otto Warmbier,

tourism,

US State Department

Saturday, August 3, 2019

Radioactive River

(The second part of this article can be found here "A Pyongsan Addendum")

North Korea is a signatory to the Paris Accords, has made plans to reforest the country, and uses propaganda to show off how clean and beautiful the country is. While it is true that the North Korean countryside can be lovely and that there are densely forested mountains, North Korea is also an impoverished industrial country with a fascination with nuclear weapons. In such regimes, industrial and military progress always takes precedent over nature and the well-being of people. One such example of this is the Ryesong River, which is heavily polluted with waste material from the Pyongsan uranium mine and concentration plant.

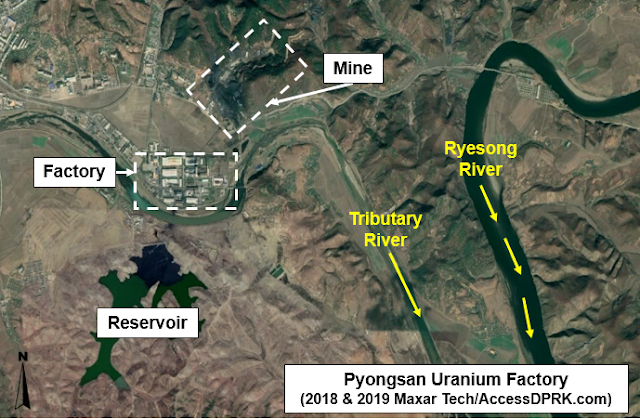

One of North Korea's two known uranium processing plants, Pyongsan lies at the confluence of two rivers, the largest being Ryesong, which flows south for approx. 80 km, through the city of Kumchon and into the Han River estuary, which is shared by both Koreas, before emptying into the Yellow Sea.

The plant concentrates uranium from coal which is mined north of the plant. Uranium can be mined out of natural ores containing higher levels of the radioactive element or it can be found in lower quality coal - which North Korea has in abundance. Getting uranium from the coal involves a lot of steps and results in literally tons of toxic water and sludge being produced.

Normal international precautions for dealing with toxic materials include limiting the amount of polluted exhaust and aerosols, treating waste water, and storing waste materials in reservoirs that are lined with multiple layers of thick sheeting to prevent the contamination of ground water.

North Korea began constructing these uranium milling facilities in the 1980s. While there's only satellite evidence of leakage dating to 2003, it is highly likely that this has been ongoing for decades. The facility itself sits near the confluence of a smaller tributary river the larger Ryesong River, meaning that anything dumped into the tributary will quickly enter the Ryesong.

For additional detail about the plant itself, check out 38North's article.

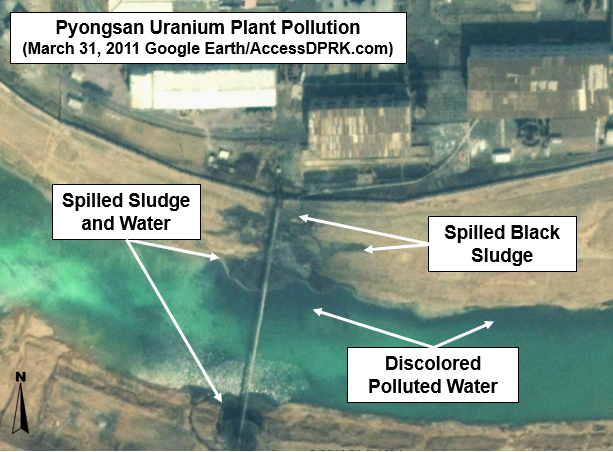

Thanks to Google Earth, we can identify (unfortunately) that the pipe taking waste materials to the open reservoir has leaks and has been spilling toxic water into the Ryesong's tributary, which is then carried downriver until it finally empties into the Han River estuary and adds to the contamination of the Yellow Sea.

In this image from 2006, a clearly identifiable layer of black sludge has accumulated beneath the waste pipe as it leaves the factory. An apparent algal bloom is also visible. Small blooms naturally happen all over the world, but they can also be the result of certain kinds of pollution. The blooms release toxins of their own and can be very harmful to fish and people.

Fast forward to 2011 and you can see that the sludge has actually piled up on the riverbed, that it is coming from both ends of the pipe, and that the polluted water is flowing downstream as it hugs the north bank of the river heading to Ryesong.

In May 2017, a leak of an unidentified white-colored material can be spotted. Like the leak from 2011, this lighter material can clearly be seen being carried downstream.

The continual spilling of material can also be clearly seen during winter. The otherwise frozen tributary river is melted at each end of the pipe, where hot waste water is being dumped directly into the river.

The waste water reservoir occupies 338,000 square meters (33.7 hectares) and doesn't appear to be lined at all. This places any groundwater and wells at great risk as well as offers more opportunities for toxic materials to seep into the river.

Around 200,000 people live near the factory and downstream along the Ryesong River. Aside from the two main cities of Pyongsan and Kumchon, there are multiple small villages that line the riverbanks. The river is the only above-ground source of water for drinking, washing, and farming. Plants grown using polluted water often concentrate those pollutants and those are then passed on to the animals and people that eat them.

The various pollutants from the factory are then added to the other runoff received by the Yellow Sea, which is home to roughly 600 million people.

River pollution is a major problem in North Korea and even affects Pyongyang's main source of drinking water.

--Jacob Bogle, 8/3/2019

www.JacobBogle.com

Facebook.com/JacobBogle

Twitter.com/JacobBogle

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)