I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters who help make all of this possible: Alex Kleinman, David M., Amanda Oh, Donald Pierce, Dylan D, Joe Bishop-Henchman, Jonathan J, Joel Parish, John Pike, Kbechs87, Russ Johnson, and Squadfan.

The AccessDPRK blog is dedicated to exposing North Korea via satellite imagery. Discussing domestic, economic and military locations and helping to uncover this hermit kingdom.

Wednesday, May 22, 2024

Lost Villages of the DMZ

Monday, April 1, 2024

Reprocessing Activity at the Pakchon Uranium Concentration Pilot Plant

The Pakchon Uranium Concentration Pilot Plant is North Korea's first uranium concentration plant. Converted from a graphite processing facility, Pakchon began to process uranium ore into "yellowcake" in 1982. Based on open-source information and satellite observations, it has likely been in caretaker status since 2002. But, as previously reported by AccessDPRK, low-level activities have continued at the plant.

According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, such low-level activities may involve "small processing runs of iron-bearing ore of some type, caretaker maintenance work, or decommissioning of equipment within the plant."

However, recent satellite imagery suggests additional kinds of activity are now taking place.

A series of chemical or slurry tanks were constructed at the waste material reservoir between September 2021 and February 2024, along with small support structures and a new ~240 sq. meter holding or settling pond.

This opens up two main possible explanations for the activity. 1) that the waste material is being reprocessed to extract rare earth elements (REEs) or even residual uranium; 2) that the plant is actually undertaking an environmental remediation program to clean up the industrial waste.

Frank V. Pabian, former IAEA Nuclear Chief Inspector for Iraq, told AccessDPRK that it is most probable that they "are setting up to process the old waste tailings pile" in search of rare earth elements in a process that, considering North Korea's command economy, "does not have to be cost effective in the normal sense of things."

Rare earth elements such as gadolinium, neodymium, and yttrium can be used for a wide range of purposes, but they have become critical for modern military and electronic technologies. With international sanctions preventing North Korea from legally importing such material, the country needs to find domestic sources.

At Pakchon, as at Pyongsan, the uranium came from coal which was then processed to concentrate the uranium into yellowcake (a low-radiation powder of concentrated U-238, mostly in the form of triuranium octoxide) before it was shipped off to Yongbyon. The waste material was then deposited in a series of reservoirs.

Although it is unlikely that Pakchon has been engaged in uranium concentration activities since 2002, it seems that North Korea has found another use for the facility.

Tailings from uranium processing can contain concentrations of other valuable minerals like REEs, but their recovery still relies on expensive and complex chemical, physical, or electrical processes.

China is the world's leading supplier (90%) of processed REEs, creating a dangerous bottleneck that could be cut off in the event of economic or military confrontation. That risk to the world's supply has seen countries scramble for alternative sources.

Investing in technologies to make REE extraction economically viable from coal waste from power plants, other industrial sources, and even municipal waste is something multiple countries, including the United States, are engaged in. However, extracting the elements out of the waste requires a combination of physical and chemical processes.

As Pabian noted, North Korea isn't always bound by traditional economic considerations. Its drive for nuclear weapons has resulted in a crippled economy for decades and numerous sanctions, and so it has sought ways to evade and break sanctions by developing synthetic fuels from its own coal supplies to funding its activities through cryptocurrency theft.

Reprocessing material from Pakchon may be yet another attempt to get the raw materials the country needs for its weapons and technology projects. It's worth noting that regardless of whatever policy directives are specific to the activities at Pakchon, North Korea has been going back to tailings and gangue piles at mining sites around the country to reprocess that material as well.

Besides the new reprocessing site, other changes at Pakchon should also be noted.

As is shown, two of the plant's support buildings had their roofs replaced between 2021 and 2024. These follow similar changes in previous years to other buildings, and reenforces the assessment that Pakchon is still being used for various activities, just not large-scale uranium processing.

With the reprocessing of waste material in search of REEs or residual uranium, however, the use of these buildings as part of that reprocessing activity can't be ruled out.

As for the possibility that the activity is related to environmental remediation efforts, I do not think that it is likely. North Korea has repeatedly demonstrated its low regard for environmental and health safety, including by allowing industrial waste to flow into the Ryesong River and by polluting the Taedong River (Pyongyang's main water source). So, it would be a rare instance of remediation and the only instance known of such efforts at a nuclear facility, if that is what is taking place at Pakchon.

I believe that these developments at Pakchon, as well as the recently discovered construction activity at the suspected Kangson Uranium Enrichment Facility, should spur a review of all known nuclear facilities as well as key mining sites to see if there are other similar changes happening.

Regardless of if the developments at Pakchon are occurring in isolation or in tandem with other sites, it serves as a reminder that North Korea will use any and all sources of raw materials to further its technology programs and to earn foreign currency regardless of its international obligations.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters who help make all of this possible: Alex Kleinman, Amanda Oh, Donald Pierce, Dylan D, Joe Bishop-Henchman, Jonathan J, Joel Parish, John Pike, Kbechs87, Russ Johnson, and Squadfan.

Sunday, March 24, 2024

North Korea's Prison Camps: 10 years later

It concluded,

"Systematic, widespread and gross human rights violations have been, and are being, committed by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, its institutions and officials. In many instances, the violations of human rights found by the Commission constitute crimes against humanity. These are not mere excesses of the state. They are essential components of a political system that has moved far from the ideals on which it claims to be founded. The gravity, scale and nature of these violations reveal a state that does not have any parallel in the contemporary world."

In the course of the last decade, evidence continues to build against the government in Pyongyang, and there is no indication that the overall human rights situation has improved. Despite changes to North Korea's prison camp system over the years, with prisons like Hoeryong Camp No. 22 closing down, satellite imagery helps to expose the current extent of the prison system and reveals that the remaining prisons continue to be active, and that some have even grown in size.

North Korea has multiple kinds of penal facilities. The most numerous are short-term, pre-trial detention centers operated by the Ministry for Social Security that are located in every county. These facilities are where the accused are initially held and interrogated. This period may last months and often involves physical and sexual abuse.

At the facility in Onsong (42.959895° 129.986655°), two major changes happened in 2023. A new 40-meter-long building was constructed in the northern section of the security complex, and more worryingly, the building where prisoners are housed was demolished and replaced with a new, multi-floor structure.

There are roughly 200 of these detention centers, but only about a dozen have been geolocated using witness testimony (based on the North Korea Prison Database). Described by Human Rights Watch as being "arbitrary, violent, cruel, and degrading", North Korean defectors told HRW that once inside the pre-trial detention system, "they had no way of knowing what would happen to them once they were arrested, had no access to an independent lawyer, and had no way of appealing to the authorities about torture or violations of the criminal procedure law."

The next type of camp is kyo-hwa-so, which are reeducation labor camps. In design, they are similar to other prisons around the world, except for the conditions within their walls.

Based on evidence gathered for the UNHRC report, one can be sent to a kyo-hwa-so facility for such crimes as possessing South Korean media or being a Christian.

These prisons may consist of a single prison facility or be comprised of a central prison with one or more satellite facilities located near forced labor sites such as mines. The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea lists approximately 40 known or suspected operational kyo-hwa-so and their satellite facilities in their 2017 report Parallel Gulag.

However, only thirteen of the main kyo-hwa-so prisons have been positively geolocated with the help of witness testimony. At least two of them (in Hamhung and Sariwon) were built during the Japanese occupation period and have continued to be used as prisons by the DPRK government.

According to the Database Center for North Korean Human Rights, prisoners at Hamhung (39.957716° 127.563103°) manufacture and repair sewing machines at the main prison compound. Additional satellite facilities (including a women's prison) exist in the region, but they haven't all been geolocated.

Other kyo-hwa-so, like the one in Sunchon (39.435983° 125.795632°), are smaller but provide the state with important commodities like gold. Sunchon is a forced labor gold mine which has expanded several times in recent years. Since 2010, the prisoner barracks at Sunchon has been enlarged 35% and security around the mining complex has been increased considerably.

The largest of the prisons in North Korea are political prison camps (kwan-li-so), which can cover tens or hundreds of square kilometers and hold many thousands of prisoners. The government started building political prisons camps in the 1950s following a series of purges, and prisoners face long, often life-term sentences.

At least fifteen of these large prison camps are known to have existed but several were closed in the 1980s and 1990s due to their proximity to the Chinese border. Many prisoners were transferred to other camps in the process.

Today, four kwan-li-so are known to remain: Kwan-li-so No. 14 (Kaechon), Kwan-li-so No. 16 (Hwasong), Kwan-li-so No. 18 (Pukchang), and Kwan-li-so No. 25 (Chongjin).

These expansive camps are further divided into two zones: the “revolutionary zone” and the “total control zone”. The “revolutionary zone” affords prisoners the chance at release after their sentences which includes ideological “reeducation” and hard labor.

According to the UNHRC report, “total control zones” are for “inmates [who] are considered ideologically irredeemable and incarcerated for life.” The report further elaborates that anyone caught attempting to escape a total control zone is summarily executed.

Covering 155 sq. km., Kwan-li-so No. 14 (Kaechon) (39.569063° 126.058896°) is located on the banks of the Taedong River and holds an estimated 36,800 prisoners as of 2022. Through the use of forced labor in the camp, small factories produce a range of products including textiles, shoes, and cement.

A review of commercial satellite images of the camp found that between 2017 and 2019 security around each prisoner housing district was increased with perimeter walls being added or rebuilt around them.

North Korea's prison camps provide millions each year to the state in economic benefits through forced labor in the agricultural, light industrial, and mining sectors. Coal is the most commonly mined commodity, and as can be seen in the above image, enough coal is mined at Kaechon that the train entering the camp is pulling 23 hopper cars, each with a carrying capacity of approximately 90 tonnes.

Kwan-li-so No. 16 (Hwasong) (41.267932° 129.394091°) is the largest prison camp in North Korea by area, covering 549 sq. km. It has been alleged that prisoners from Camp 16 were used in the construction of tunnels at the nearby Punggye-ri Nuclear Test Facility.

It was reported that facilities at several camps including Camp 16 were expanded in 2014 to accommodate a large influx of new prisoners related to the purges associated with the execution of Kim Jong Un’s uncle, Jang Song-thaek. A review of satellite imagery does show a range of changes to Camp 16 that include additional prisoner housing, workshops, and infrastructure projects.

Kwan-li-so No. 18 (Pukchang) (39.562888° 126.077457°) is the oldest existing political prison camp, having been established in the 1950s. It was downsized between 2006 and 2011, but a review of satellite imagery shows that the camp is still active and that new guard facilities were constructed ca. 2014, and that an additional security fence was built ca. 2019.

DailyNK reported that individuals associated with the failed 2019 Hanoi Summit between Kim Jong Un and President Donald Trump were sent to Pukchang for punishment.

Kwan-li-so No. 25 (Chongjin) (41.833620° 129.726124°) is the smallest of the four active political prison camps and there are no first-hand witness accounts of life in the camp. Based on information released during the 9th International Conference on North Korean Human Rights and Refugees (2009), many of the prisoners at Camp 25 are religious leaders and their families, along with people of Korean-Japanese descent who became dissidents.

Camp No. 25 is the only example of a camp where the entire prison is administered as a "total control zone".

The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea noted a large expansion of the camp’s outer perimeter and the addition of seventeen guard posts in 2010. A review of satellite imagery by NK Pro also found that a light-industrial building was razed in 2018-19, a new 450-square-meter building was constructed in 2020, and that the prison’s main gate was renovated in 2023, among other findings.

Together, the kyo-hwa-so and kwan-li-so hold around 200,000-250,000 prisoners, with DailyNK estimating that the eight largest prisons held a combined 205,000 individuals as of 2022. There are also upwards of 700 other penal facilities such as pre-trial detention centers and local "labor training" facilities (rodong kyoyangdae and rodong danryondae) that hold thousands more.

Although the number of defections has dramatically decreased due to the "border blockade" instituted in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the testimonies of those who continue to risk their lives crossing the border reveal that life inside of North Korea remains bleak. And for those languishing in Kim Jong Un's constellation of prisons, loss of their rights, attacks on their dignity, and physical abuse remains a daily occurrence.

Despite a major increase in the level of knowledge and public reporting about North Korea, there seems to have been few if any meaningful changes in the country's human rights record or judicial system to redress the many deficiencies that have been highlighted by the UN Human Rights Council and NGOs from around the world.

Particularly in light of China's reluctance to enforce UN sanctions and Russia's abandonment of the UN Charter with respect to Ukraine (and subsequently engaging in patently illegal arms trade with North Korea), attempts to hold North Korea accountable for its gross violations of international law appear to face even greater odds. However, there are still multiple avenues that can and must be taken by individuals and individual nation states to prevent this behavior - which has been ongoing since the foundation of the DPRK - from continuing for another eighty years.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters who help make all of this possible: Alex Kleinman, Amanda Oh, Donald Pierce, Dylan D, Joe Bishop-Henchman, Jonathan J, Joel Parish, John Pike, Kbechs87, Russ Johnson, and Squadfan.

Sunday, February 25, 2024

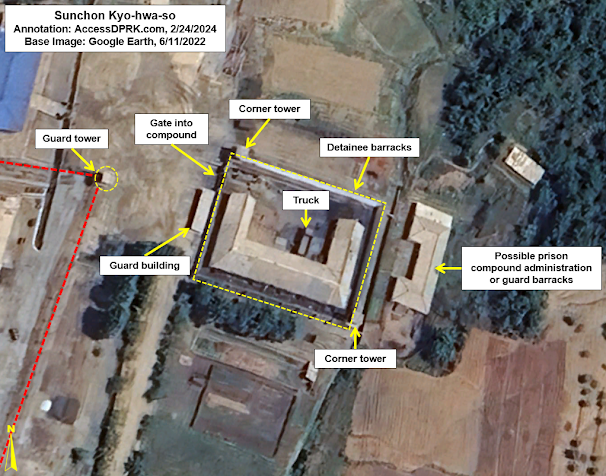

A Review of the Sunchon Kyo-hwa-so

Located in the mountains west of the city of Sunchon, near a village called Unbong-dong, is a little-known reeducation labor camp (kyo-hwa-so) at 39.436033° 125.795551°.

Kyo-hwa-so are for those prisoners the regime considers "redeemable". Detainees are required to undergo ideological training and must endure forced labor. According to the UN Human Rights Council Commission of Inquiry report, detainees are also likely to experience beatings, torture, sexual assault, and starvation rations.

Several kyo-hwa-so have been the subject of detailed reports through the work of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea and other organizations, but the Sunchon facility has no known survivors to offer up witness testimony. It was mentioned in the 2017 report Parallel Gulag, but I would like to take this opportunity to lay out its developmental history in detail.

Despite the sparsity of direct information, it is known that the prison is a gold mine that relies on forced labor. And through the analysis of satellite imagery, a lot more can be learned.

The earliest commercially available high-resolution image of the camp is 2002. A review of Landsat imagery shows activity at the site in 2001, but there's little indication of a prison or mining activity prior to that; although, there is low-level deforestation at the site beginning in the late 1980s. If the prison existed before 2000, it was quite small.

In the December 9, 2002 image, buildings exist at the prison site but there are no obvious security features such as a fence or perimeter wall, and no obvious guard posts.

This site is one of the first of what will become an extended mining region, and another mine entrance exists at this time 1.3 km to the west at 39.442718° 125.781264°.

The next available image is from 2006. By then, a perimeter wall clearly surrounds the detainee facility and encloses an area of 1,400 sq. meters. The building covers approximately 280 sq. meters. The main mining facility and tailings pond were also enlarged.

Elsewhere in the immediate region, additional mining sites have opened up by 2006, but none appear to be prisons.

By May 2009, a new wing of the detainee facility was constructed, enlarging the building to approximately 370 sq. meters. This could indicate an increase in the number of detainees held at the prison. Also, the two corner guard towers were reconstructed.

Additionally, a small building immediately to the east of the detainee facility was razed.

The main mining building was also reconstructed and takes on the appearance of a typical ore processing plant, and a second tailings pond was opened.

By September 2010, where the building was razed in 2009, a new building was constructed in its place. The new building is ~210 sq. meters which is more than double the size of the older building. It could be associated with the prison's administration, but that can't be said with certainty.

Based on the tailings ponds, mining activity during this period was being carried out at a consistent pace.

Between 2011 and 2013, the detainee facility was enlarged yet again, with a further 80 sq. meters added.

Activity at the other nearby mines also increased at a similar rate to the activity at the kyo-hwa-so mine.

Between 2016 and 2017, a fence was added to partially block off the mine from the rest of the surrounding area. Prior to this time, there was no clear delineation between the mine's territory and the outside, civilian area.

Construction also took place at the detainee facility, with the addition of new walls (although incomplete in September). That work was finished in October 2017, bringing the size of the building to approx. 500 sq. meters.

By the end of 2019, a more robust perimeter fence was constructed around the mine, completely enclosing it, and three guard towers were also added.

Between 2020 and 2022, the main administrative building of the mine was reconstructed. The mining facilities were also further developed.

Based on the imagery, prisoners are transported from the walled detention facility to the mine via truck. The distance from the gate at the detention facility to the gate at the mine's fence is only ~36 meters, and then it's a further ~90 meters to the primary ore processing building.

The other mines in the area have all been further developed and grown, but none of them have indicators of being part of the kyo-hwa-so, and thus likely do not use forced labor.

Citing the Database Center for North Korean Human Rights, Parallel Gulag says that this kyo-hwa-so has an estimated detainee population of 400. Given the multiple expansions of the detainee barracks, I think it's possible that this prison now holds as many as 600 people.

Between the large kwan-li-so concentration camps, kyo-hwa-so reeducation camps, pre-trial detention centers, local labor training centers (rodong kyoyangdae and rodong danryondae), and military prison camps, North Korea operates a constellation of several hundred* penal facilities. The eight largest prisons are estimated to contain 205,000 detainees.

As evidenced by the Sunchon kyo-hwa-so, these detainees aren't simply serving a prison sentence but are used to help supplement state revenue. Millions of dollars' worth of gold and other minerals are extracted, and military uniforms, textiles, foodstuffs, furniture, shoes, and numerous other products are produced in the country's prisons. The revenue from those products can then be used by the Kim Jong Un regime to fund its other activities.

Although some prisons have been closed in the last 15 years (the Hoeryong and Yodok camps), Pyongyang has merely been consolidating its prison camp system and putting resources into extracting as much as possible out of its captive population.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters who help make all of this possible: Alex Kleinman, Amanda Oh, Donald Pierce, Dylan D, Joe Bishop-Henchman, Jonathan J, Joel Parish, John Pike, Kbechs87, Russ Johnson, and Squadfan.

*Note: the Ministry of Social Security and the Ministry of State Security each operate short-term detention/interrogation facilities in nearly every county in North Korea. Additionally, the full extent of military-operated camps (such as Camp 607) and local "labor training centers" has not yet been discovered.

Sunday, January 21, 2024

DPRK's Fuel Transport and Storage Network: an Introduction

North Korea doesn't have its own domestic supply of oil and relies on legal and illicit transfers of petroleum products for its economy to function. While AccessDPRK has documented the proliferation of gas stations around the country, those exist parallel to North Korea's traditional oil storage and delivery network, which it has maintained for decades.

In much of the world, going to your local gas station is how most individuals get fuel. There are stations for cars, trucks, and there are dedicated fueling depots used for institutions that have large fleets of vehicles like municipalities. But until recently, getting fuel in North Korea wasn't so simple.

Sixty-nine percent of the 190 gas stations identified by AccessDPRK have been built under Kim Jong Un, and even those aren't enough to cover every town and village - let alone the needs of factories, universities, collective farms, and other organizations that operate multiple vehicles and pieces of equipment.

So, most organizations still rely on an older system of refueling.

While the specifics of how this system works remains little understood, I feel that I have been able to locate enough of the infrastructure (which is often buried underground or in hardened structures) to write an introduction to this system that serves as the backbone of fuel delivery and storage in North Korea.

To place this system in context, I'll quickly review North Korea's petroleum infrastructure.

North Korea is only allowed to legally import 4 million barrels of unrefined petroleum products and 500,000 barrels of refined petroleum products (like gasoline and kerosene) each year under United Nations' restrictions.

North Korea imports petroleum products via ship and rail transfers as well as from a single pipeline coming from China into Sinuiju, the PRC-DPRK Friendship Oil Pipeline. North Korea has two refineries but largely relies on the Ponghwa Chemical Factory which is nearest Sinuiju.

From its refineries and system of storage depots at key coastal terminals, legal (and an ever increasing amount of illegal) petroleum products are then transported to intermediate depots around the country.

As mentioned, part of the fuel is sent from those terminals via rail and then truck to the country's gas stations.

But as you can see, they are not evenly distributed around the country and also only provide a limited storage capacity.

The bulk of the nation's fuel gets stored elsewhere, at facilities large and small, and can then be transported to factories, farms, and other organizations that need to fuel their own vehicles and equipment.

I currently have nearly ninety of these internal storage sites located. As mentioned earlier, most of the facilities are either underground or located within covered/hardened bunkers, making their identification difficult. Most, however, are near railways and so I believe I will be able to locate a considerably greater number of them in the future.

But with the sites that have been located, I can show each of the steps from the main terminals down to the local level.

Nampo's key petroleum depot is located at 38.720407° 125.366678°. It is one of North Korea's most important petroleum storage facilities, and also receives shipments from vessels engaged in illegal transshipment operations.

Currently it has fifteen storage tanks for different types of refined petroleum products. The depot has grown in recent years with two new tanks added since 2019, and there is prepared space for a further twelve tanks. Two additional facilities also lie within a few hundred meters from this site.

Taedong Storage Site 39.094303° 125.615255°

From the main receiving depots like Nampo, petroleum can be shipped by rail to intermediate storage facilities. This one is near the town of Taedong, west of Pyongyang.

At Taedong, four large storage tanks - each approx. 20 to 25 meters in diameter - are partially set underground and are covered with large mounds of dirt.

Oil is brought to them via a pipeline from a rail terminal 750 meters away. Once inside the complex, the main line splits into smaller feeder pipelines that can fill or drain each tank independently. Taedong is one of the largest of these internal facilities and is just 1.3 km away from five anti-aircraft artillery batteries, and it is covered by several surface-to-air missile sites as well owing to its proximity to Pyongyang.

Within Pyongyang is a large, central storage facility at 39.082890° 125.707182°.

The complex covers 12.4 hectares and contains large storage tanks like at Nampo, and smaller tanks that can be seen in towns outside of the capital and even at gas stations.

From these larger storage facilities, the fuel is then distributed via tanker trucks to their destined town or village.

One such site is in Kuum-ni at 38.898954° 127.908719°.

Over time, most of the open tank facilities like Kuum-ni have had their storage tanks placed in bunkers or covered over with soil. In this 2013 image, new vent pipes are visible as small white dots.

Civilian organizations (factories, farms, etc.) have their own on-site fuel storage, and can draw from these "community" facilities. Sometimes it's a considerable amount (thousands of liters) or just a few small storage barrels, depending on their individual needs.

The military has its own fuel supply system, and their needs are prioritized over civilian organizations.

This system, while theoretically efficient in a country lacking internal pipelines, is also prone to abuse as local party bosses have considerable influence over the local fuel supply. And, there many opportunities for fuel to be stolen or diverted elsewhere; from black market activity to diversion for personal use, and the occasional need to 'donate' fuel back to the government, an unknown but likely large percentage of the country's fuel supplies end up being taken out of normal availability.

Regardless of the inefficiencies in North Korea's supply structure and economic policies, the country has managed to continue to import far more fuel than UN limits allow, even through the border closures brought on by the pandemic.

Given a lack of comprehensive data about North Korea's imports, monitoring other parts of the country's petroleum infrastructure, like the growth, renovation, or demolition of storage facilities, can provide additional insight into how much the country is capable of bringing in and storing long-term.

Petroleum storage, while not always the most interesting subject, plays a role in North Korea's ability to withstand sanctions, border closures, and any future blockade during a war. Improving our understanding of this topic can also help us to gauge the strength of its economy and its ability to manufacture a range of goods.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters who help make all of this possible: Alex Kleinman, Amanda Oh, Donald Pierce, Dylan D, Joe Bishop-Henchman, Jonathan J, Joel Parish, John Pike, Kbechs87, Russ Johnson, and Squadfan.

Friday, December 22, 2023

Farming on the Frontier

North Korea shares 1,369.3 km of border with China and Russia. Predominately demarcated by the Yalu and Tumen rivers, the border regions are mountainous, with the available farmland often squeezed into thin strips or even onto islands that completely flood every few years.

With a few exceptions, such as the plains around Taehongdan and Onsong, farming in this region doesn't contribute significant amounts to the national food supply. However, they are important locally as are the forests which harbor herbs, mushrooms, and other plants used for food and in traditional medicines, and access to these lands provides additional income to local farmers and foragers.

But, the government's response to the COVID-19 pandemic has placed that access at risk.

Through the construction of two layers of border fence, the land in between has become subjected to additional checkpoints, and many of the forests have become completely off limits.

North Korea has attempted to secure the full border in the past but never succeeded in doing so until COVID-19. Using the pandemic as justification, even the most impassable parts of the border are now fenced off with over 1,000 km of new fencing and thousands of additional guard posts having been constructed.

As seen in the next image, the double row of fencing cuts through not only mountainous regions but also through farmland, disrupting the typical flow of human activity in those areas.

Sometimes those fences are separated by only a few meters but in other areas it can be as much as a kilometer. In total, over 260 sq. km. of farmland and forest lies between the two fences, cut off from easy access.

Positioned along roads that pass through the secondary fence are small checkpoints to verify the identification of everyone that tries to enter the border region. Not all of the existing road network remains open, however, with the fence just cutting across the road, and closing it. By limiting the number of access points, North Korea can funnel activity through a more manageable number of fence crossings, increasing overall security.

However, the fence doesn't only impact official farms. Illegal plots of farmland (sotoji) have been an integral part of North Korea's black market economy for decades, and they play an important role in supporting local economies and supplementing local food supplies, with corn, cabbage, potatoes, and soybeans being common crops.

Although the land in between the fences (and the illegal farms it holds) no longer appear to be openly accessible, entry to the sotoji could still be possible by bribing checkpoint officers as bribery and corruption is already rife in North Korea. If bribes are required, however, that is yet one more slice of income taken away from farmers (who, in the case of sotoji, could be anyone from professional farmers, teachers, and miners, to retired persons).

If, however, access to the land has been permanently blocked and many or most of the fields are no longer cultivated, then that will have a direct impact on the many small villages and hamlets that can be found along the border region.

In this area (imaged above) northeast of Pyoktong, North Pyongan Province, sotoji comprise roughly half of the land with forests occupying the other half.

Nationwide, an estimated 550,000 hectares are suspected of being sotoji, and DailyNK estimated that some 20% of all grain grown in the country in 2007 came from these irregular farms. Of course, land use patterns evolve over time, but as Andrei Lankov wrote in 2011, "the percentage of land under the cultivation of sotoji owners roughly equals that under cultivation by state-run farms" in some counties that border China. And, indeed, numerous of these illegal plots can be found within the new border fence area.

Crop yields nationwide have struggled in the last few years, but there haven't been any studies yet that focus on the border area that might tell us how the sotoji have fared with the construction of the border fence.

Whether it's a border blockade cutting off cross-border trade and impacting the lives of thousands living in the villages and hamlets of the area, or whether it's the construction of scores of additional checkpoints between towns and counties, and even surrounding Pyongyang, the government has used the pandemic as an excuse to crack down on human movement in ways greater than ever before.

Unfortunately, the difficulties imposed by the dual-layer border fence system on local populations aren't likely to lessen as authorities continue to extend the state's power over the economy and the freedom of movement.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters who help make all of this possible: Alex Kleinman, Amanda Oh, Donald Pierce, Dylan D, Joe Bishop-Henchman, Jonathan J, Joel Parish, John Pike, Kbechs87, Russ Johnson, and Squadfan.