It concluded,

"Systematic, widespread and gross human rights violations have been, and are being, committed by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, its institutions and officials. In many instances, the violations of human rights found by the Commission constitute crimes against humanity. These are not mere excesses of the state. They are essential components of a political system that has moved far from the ideals on which it claims to be founded. The gravity, scale and nature of these violations reveal a state that does not have any parallel in the contemporary world."

In the course of the last decade, evidence continues to build against the government in Pyongyang, and there is no indication that the overall human rights situation has improved. Despite changes to North Korea's prison camp system over the years, with prisons like Hoeryong Camp No. 22 closing down, satellite imagery helps to expose the current extent of the prison system and reveals that the remaining prisons continue to be active, and that some have even grown in size.

North Korea has multiple kinds of penal facilities. The most numerous are short-term, pre-trial detention centers operated by the Ministry for Social Security that are located in every county. These facilities are where the accused are initially held and interrogated. This period may last months and often involves physical and sexual abuse.

At the facility in Onsong (42.959895° 129.986655°), two major changes happened in 2023. A new 40-meter-long building was constructed in the northern section of the security complex, and more worryingly, the building where prisoners are housed was demolished and replaced with a new, multi-floor structure.

There are roughly 200 of these detention centers, but only about a dozen have been geolocated using witness testimony (based on the North Korea Prison Database). Described by Human Rights Watch as being "arbitrary, violent, cruel, and degrading", North Korean defectors told HRW that once inside the pre-trial detention system, "they had no way of knowing what would happen to them once they were arrested, had no access to an independent lawyer, and had no way of appealing to the authorities about torture or violations of the criminal procedure law."

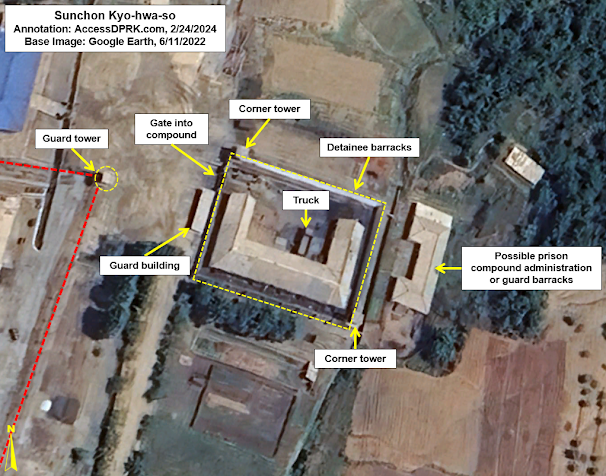

The next type of camp is kyo-hwa-so, which are reeducation labor camps. In design, they are similar to other prisons around the world, except for the conditions within their walls.

Based on evidence gathered for the UNHRC report, one can be sent to a kyo-hwa-so facility for such crimes as possessing South Korean media or being a Christian.

These prisons may consist of a single prison facility or be comprised of a central prison with one or more satellite facilities located near forced labor sites such as mines. The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea lists approximately 40 known or suspected operational kyo-hwa-so and their satellite facilities in their 2017 report Parallel Gulag.

However, only thirteen of the main kyo-hwa-so prisons have been positively geolocated with the help of witness testimony. At least two of them (in Hamhung and Sariwon) were built during the Japanese occupation period and have continued to be used as prisons by the DPRK government.

According to the Database Center for North Korean Human Rights, prisoners at Hamhung (39.957716° 127.563103°) manufacture and repair sewing machines at the main prison compound. Additional satellite facilities (including a women's prison) exist in the region, but they haven't all been geolocated.

Other kyo-hwa-so, like the one in Sunchon (39.435983° 125.795632°), are smaller but provide the state with important commodities like gold. Sunchon is a forced labor gold mine which has expanded several times in recent years. Since 2010, the prisoner barracks at Sunchon has been enlarged 35% and security around the mining complex has been increased considerably.

The largest of the prisons in North Korea are political prison camps (kwan-li-so), which can cover tens or hundreds of square kilometers and hold many thousands of prisoners. The government started building political prisons camps in the 1950s following a series of purges, and prisoners face long, often life-term sentences.

At least fifteen of these large prison camps are known to have existed but several were closed in the 1980s and 1990s due to their proximity to the Chinese border. Many prisoners were transferred to other camps in the process.

Today, four kwan-li-so are known to remain: Kwan-li-so No. 14 (Kaechon), Kwan-li-so No. 16 (Hwasong), Kwan-li-so No. 18 (Pukchang), and Kwan-li-so No. 25 (Chongjin).

These expansive camps are further divided into two zones: the “revolutionary zone” and the “total control zone”. The “revolutionary zone” affords prisoners the chance at release after their sentences which includes ideological “reeducation” and hard labor.

According to the UNHRC report, “total control zones” are for “inmates [who] are considered ideologically irredeemable and incarcerated for life.” The report further elaborates that anyone caught attempting to escape a total control zone is summarily executed.

Covering 155 sq. km., Kwan-li-so No. 14 (Kaechon) (39.569063° 126.058896°) is located on the banks of the Taedong River and holds an estimated 36,800 prisoners as of 2022. Through the use of forced labor in the camp, small factories produce a range of products including textiles, shoes, and cement.

A review of commercial satellite images of the camp found that between 2017 and 2019 security around each prisoner housing district was increased with perimeter walls being added or rebuilt around them.

North Korea's prison camps provide millions each year to the state in economic benefits through forced labor in the agricultural, light industrial, and mining sectors. Coal is the most commonly mined commodity, and as can be seen in the above image, enough coal is mined at Kaechon that the train entering the camp is pulling 23 hopper cars, each with a carrying capacity of approximately 90 tonnes.

Kwan-li-so No. 16 (Hwasong) (41.267932° 129.394091°) is the largest prison camp in North Korea by area, covering 549 sq. km. It has been alleged that prisoners from Camp 16 were used in the construction of tunnels at the nearby Punggye-ri Nuclear Test Facility.

It was reported that facilities at several camps including Camp 16 were expanded in 2014 to accommodate a large influx of new prisoners related to the purges associated with the execution of Kim Jong Un’s uncle, Jang Song-thaek. A review of satellite imagery does show a range of changes to Camp 16 that include additional prisoner housing, workshops, and infrastructure projects.

Kwan-li-so No. 18 (Pukchang) (39.562888° 126.077457°) is the oldest existing political prison camp, having been established in the 1950s. It was downsized between 2006 and 2011, but a review of satellite imagery shows that the camp is still active and that new guard facilities were constructed ca. 2014, and that an additional security fence was built ca. 2019.

DailyNK reported that individuals associated with the failed 2019 Hanoi Summit between Kim Jong Un and President Donald Trump were sent to Pukchang for punishment.

Kwan-li-so No. 25 (Chongjin) (41.833620° 129.726124°) is the smallest of the four active political prison camps and there are no first-hand witness accounts of life in the camp. Based on information released during the 9th International Conference on North Korean Human Rights and Refugees (2009), many of the prisoners at Camp 25 are religious leaders and their families, along with people of Korean-Japanese descent who became dissidents.

Camp No. 25 is the only example of a camp where the entire prison is administered as a "total control zone".

The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea noted a large expansion of the camp’s outer perimeter and the addition of seventeen guard posts in 2010. A review of satellite imagery by NK Pro also found that a light-industrial building was razed in 2018-19, a new 450-square-meter building was constructed in 2020, and that the prison’s main gate was renovated in 2023, among other findings.

Together, the kyo-hwa-so and kwan-li-so hold around 200,000-250,000 prisoners, with DailyNK estimating that the eight largest prisons held a combined 205,000 individuals as of 2022. There are also upwards of 700 other penal facilities such as pre-trial detention centers and local "labor training" facilities (rodong kyoyangdae and rodong danryondae) that hold thousands more.

Although the number of defections has dramatically decreased due to the "border blockade" instituted in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the testimonies of those who continue to risk their lives crossing the border reveal that life inside of North Korea remains bleak. And for those languishing in Kim Jong Un's constellation of prisons, loss of their rights, attacks on their dignity, and physical abuse remains a daily occurrence.

Despite a major increase in the level of knowledge and public reporting about North Korea, there seems to have been few if any meaningful changes in the country's human rights record or judicial system to redress the many deficiencies that have been highlighted by the UN Human Rights Council and NGOs from around the world.

Particularly in light of China's reluctance to enforce UN sanctions and Russia's abandonment of the UN Charter with respect to Ukraine (and subsequently engaging in patently illegal arms trade with North Korea), attempts to hold North Korea accountable for its gross violations of international law appear to face even greater odds. However, there are still multiple avenues that can and must be taken by individuals and individual nation states to prevent this behavior - which has been ongoing since the foundation of the DPRK - from continuing for another eighty years.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters who help make all of this possible: Alex Kleinman, Amanda Oh, Donald Pierce, Dylan D, Joe Bishop-Henchman, Jonathan J, Joel Parish, John Pike, Kbechs87, Russ Johnson, and Squadfan.

No comments:

Post a Comment