North Korea operates hundreds of prisons and detention centers of various types, but only a couple dozen current and former sites have been properly identified through the use of satellite imagery and witness testimony.

In this article, I want to review the Tongrim reeducation camp (properly known as Kyo-hwa-so No. 2, Tongrim). Although there is little public information available (as with the Sunchon kyo-hwa-so), I want to provide a baseline of information about its history and development (as observed by satellite imagery) to help facilitate future research.

The reeducation camp (which are known as a kyo-hwa-so) at Tongrim is one such facility that has been mentioned by defectors - although not in detail - and listed in human rights reports going back to at least 2011 (by the Database Center for North Korean Human Rights). While its exact location has not been verified by prison survivors, former guards or former local residents, through the use of commercial satellite imagery a clear candidate stands out.

Located at (39.877265° 124.727696°) 2.6 km northeast of the Tongrim train station is this complex of buildings and walled compounds.

North Korean authorities began arresting political opponents as early as 1947 (before the actual founding of the North Korean state), and the number of prisons proliferated through the 1950s and 1960s.

When Kyo-hwa-so No. 2 was established isn't known, but declassified low-resolution (2-4 ft) imagery from the KH-9 satellite shows the site going back to at least 1973, meaning the prison was established some time before then. Earlier images from the USGA's EarthExplorer program exist but their resolutions are too low to make any clear determination.

Kyo-hwa-so reeducation camps are typically used to house "redeemable" prisoners. Following a period of hard labor and ideological “training”, prisoners may be released. The larger kwan-li-so political prison camps house more serious offenders and prisoners are held for a longer period of time or even for the rest of their lives.

All known kyo-hwa-so and kwan-li-so prison camps use forced labor. From mining coal to making uniforms and even fake eyelashes, proceeds from prison labor provides millions of dollars in revenue to the state each year.

Having said that, the exact forms of forced labor used at Tongrim aren't known. However, the prison sits at the base of a stone quarry, so it's logical to assume that the prisoners are used to extract stone (among other activities).

The earliest high-resolution commercial imagery of Tongrim comes from 2005.

By 2010, the workshop area by the prison's administration, noted in the 2005 image, had conclusively been converted into a barracks, and a perimeter wall was erected around the site. The new building within the perimeter wall has approximately 600 sq. m. of floor space and the wall enclosed an area of nearly 3,800 sq. m. This addition may have provided space for up to 500 new prisoners or to create an area to segregate a new class of prisoners among the existing population (segregated by sex, severity of the crimes, or perhaps by songbun class).

An entrance gate and guard tower were added, as well as a smaller tower in the northernmost corner of the new compound.

At the main prisoner compound, a new 26-meter-long building was constructed.

Between 2005 and 2010, little changed at the quarry.

By 2014, a new ~120 sq. m. building had been constructed within the main prison compound.

In the administrative area, an unidentified building had its roof replaced (now covered in blue tiles). The removal of the old roof is actually visible in the 2012 image, but it's not annotated.

In the main prison compound, between 2014 and 2017, the 26-meter-long building that was constructed ca. 2010 had been razed. And between 2017 and 2019, the ~120 sq. m. building that was built ca. 2014 was also razed.

Additionally, the greenhouses in the small walled compound were also removed between 2018 and 2019.

The 2014 to 2019 timeframe represents the first period of major demolition at Tongrim.

The biggest change in 2023-24 was the total demolition of the workshop buildings within the main prison compound. Whether this is a permanent situation or if they will rebuild a new one, only time will tell. But it follows a multi-year trend of demolitions.

The demolition trend extends to the quarry site as well, with the railway building being razed in 2023-24. At this part of the quarry, only two of the eleven or so nearby support buildings that existed in 2005 still stand today, and the explosives storage site also remains closed.

Importantly, the prison's rail connection to the main Pyongui Line (2.7 km south of the quarry) was removed ca. 2020-21, and the last section of rails were removed from the quarry in either 2023 or early 2024.

A comparison of images from 2010 and 2024 (below) paints a fairly clear picture that quarry operations are being wound down if they haven't yet been stopped entirely.

I want to take the opportunity to also talk about some other features and changes to the prison that deal more directly with people's lives.

As mentioned near the beginning, Kyo-hwa-so No. 2 has a separate walled building in the administrative area. The building is ~26 meters long and is surrounded by a wall that is positioned quite close to the building itself. It has its own entry gate to the south and there is a guard tower on the northeast corner of the wall.

Also of note, despite the demolition of other buildings around the prison, security has been tightened around the main prisoner barracks.

In December 2022, the barracks was surrounded by a tall wall as the primary physical barrier.

The last activity at Tongrim I want to discuss is the visibility of a large number of prisoners on the March 8, 2024 image. Catching individuals on satellite is uncommon and one of the most cited examples, at Chongjin in 2018, showed but a handful of individuals.

But in the below image, over 100 individuals are visible and more can be seen walking along the main road nearer the quarry. And this is just the most recent example, as prisoners can be seen in several previous images on Google Earth.

It can perhaps be easy when viewing sites through satellite to forget that the places we look at are connected to human beings living real lives. Whether it's a school, factory, prison, or any other place, the pixels we're seeing are comprised of the lives, struggles, work, and happiness of other people.

Unfortunately, the one's we're seeing below are made up from a regime that commits among the worst human rights abuses in history and does so through the torment of countless individuals, many of whom committed no crime that would be recognized anywhere else in the world.

North Korea has hundreds of penal facilities of numerous types and sizes with Kyo-hwa-so No. 2 making up one small part of a system that imprisons over 150,000 at any given moment. And through this review, we can see that North Korea's detention system continues to be dynamic, with new buildings constructed, old buildings removed, and people marched from place to place engaged in forced labor throughout all seasons.

Kyo-hwa-so No. 2 also provides some insight into changes within the overall system.

Although none of the prisoner barracks or security installations of Kyo-hwa-so No. 2 have been removed, the removal of multiple workshops and other support buildings throughout the complex suggests that the prison is undergoing a reorganization and may be preparing to be downsized, as occurred at Kyo-hwa-so No. 88 in Wonsan, and its human "resources" reengaged in other types of labor.

Indeed, DailyNK reported in 2017 that Tongrim was actually converted into an orphanage. However, that use is hard to reconcile with the visible security features at the site such as the new fence erected around the barracks, and the fact that dedicated orphanages already exist. If there was such a change at Tongrim, then it is an orphanage in name only. In practice, it would serve more as a juvenile detention facility where the children are treated little better than adult prisoners (and also used for forced labor).

These changes highlight the need for continued observation of Tongrim but in the end, witness testimony will be required to answer some of these questions. Ultimately, it is up to the North Korean government to begin to uphold its obligations under domestic and international law, to cease the operation of its vast constellation of prisons, to allow independent international observers to visit all prisons to document any human rights abuses, and to place those responsible for crimes against humanity at the hands of justice.

Other prison reviews by AccessDPRK:

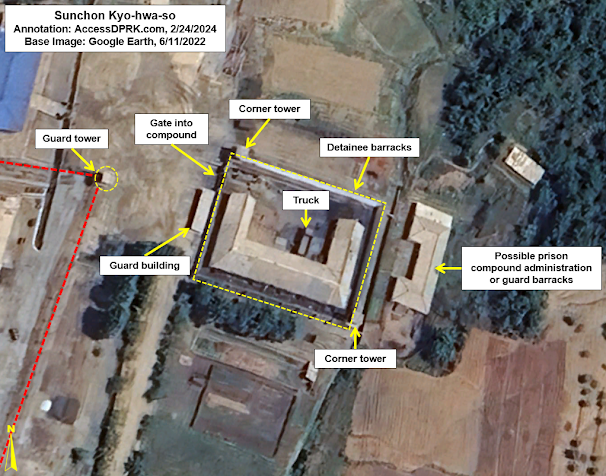

1. Review of the Sunchon Kyo-hwa-so (2024)

2. Is Wonsan Prison No. 88 Closing? (2021)

3. Chongjin Prison Camp Update (2019)

4. Prison Camp No. 22 Today (2018)

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters who help make all of this possible: Donald Pearce, David M., Dylan D, Joe Bishop-Henchman, Joel Parish, John Pike, Jonathan J., Kbechs87, Raymond Ha, Russ Johnson, Squadfan, and Yong H.