North Korea has always struggled to supply its armed forces with modern weapons and technology. Major reasons for this can be traced to the flaws inherent to a command economy, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and more recently, multiple layers of international sanctions as a response to North Korea's nuclear program.

However, what North Korea lacks in advanced technology or from their lack of access to international markets, the country endeavors to make up for by using an ever-growing military-industrial complex fueled by indigenous designs and manufacturing processes (with the help of occasionally stolen/illicitly acquired foreign research).

To facilitate this, as every country strives for, North Korea seeks to extract domestic supplies of strategic raw materials for their tanks, planes, and missiles.

For the United States, the National Mining Association noted that there are 46 metals and minerals that are critical to national security and yet accessing adequate supplies requires overseas imports. If a country as mineral rich as the US needs to import so many raw materials, the situation can only be worse for much smaller North Korea.

Through the 1950s and 1960s, Soviet and Eastern European geologists conducted several surveys of North Korean territory to find what mineral deposits existed and which ones could be extracted. Later surveys by Chinese, Japanese, South Korean, and other firms have since refined those earlier efforts.

This enabled the country to expand its access to things like iron, copper, and coal. And recent estimates suggest that North Korea could be sitting on $7-10 trillion in mineral wealth, opening up greater opportunities to provide the raw materials necessary to fuel its defense needs, even if the country still lacks some the materials used in the most advanced technologies (such as beryllium).

Complicating matters, however, is that its mining industry remains underdeveloped and North Korea's technical ability to cast, forge, alloy, and otherwise fully exploit the properties of a number of these materials remains limited.

From copper to zinc, the capacity to mine (or produce synthetically in the case of certain nuclear elements) these materials on North Korean soil would give the country a buffer against sanctions and enable them to continue work on more and more advanced technologies including a modernized nuclear arsenal. To this end, new rounds of investment in the mining industry has occurred from both domestic and international sources, and the country has been able to open new mines, reopen others shuttered years ago, and maintain operations at their key facilities.

The AccessDPRK Map 2021 Version located 2,001 mining locations. A plurality of these mines are coal mines, but coal mines offer more than a fossil fuel and can be a source of numerous other minerals. And although many individual mines in North Korea are unidentified, the minerals extracted can be determined visually for some, and others are indeed publicly known. This gives me the opportunity to list a number of specific mines that likely play key roles in providing raw materials for North Korea's national defense.

Pyongsan Uranium Mine and Concentration Plant (38°19'28.46"N 126°26'12.29"E)

According to researchers Sherzod R. Kurbanbekov, Seung Min Woo, and Sunil S. Chirayath "North Korea has at least 4 million tons of natural uranium ore reserve for industrial development, and hence total natural uranium feed available is 4,000,000kg (assuming 1000ppm ore quality). This means that the DPRK program is not constrained by the availability of natural uranium."

That's enough for around 700 highly enriched uranium-based nuclear warheads and would supply their nuclear program for years to come.

North Korea has several large uranium deposits in Pyongsan, Pakchon, Aoji (Undok), Kumchon, and other areas. This supply comes largely from coal mines as lower quality forms of coal contain a wide range of other minerals that can include uranium.

Currently, the coal mine at Pyongsan is North Korea's primary source of uranium. The Pyongsan Uranium Concentration Plant was constructed ca. 1990 and is the only declared site that still produces "yellowcake" uranium - ore that has been concentrated to 80% uranium oxide.

The ore is transported via pipeline from the mine to the concentrate plant half a kilometer away. At the plant the ore is processed and the uranium is concentrated into yellowcake before being taken to the Yongbyon Nuclear Scientific Research Center where it is further refined into highly enriched uranium and becomes suitable for nuclear warheads.

Jongchon Graphite Mine (37°55'8.52"N 126° 6'49.64"E)

This graphite mine was established in 2003 as a joint venture with the South Korean company KORES and had an initial investment of $5.5 million. The plan envisioned an annual production of 3,000 tons and allowed each side to keep half of the graphite. The mine opened in 2006 after a total investment of $10.2 million.

The graphite at Jongchong is mined from mineral-bearing soil and gravel that is then processed to separate the graphite. The waste material is then dumped as a slurry into a holding pond.

Naturally occurring graphite can be used for vehicle lubricants, batteries, crucibles/foundries, and numerous other purposes. Graphite used in nuclear reactors is synthetic and Jongchon would not be a source for the materials needed to produce it.

At the time the mine opened, it was estimated that the annual 1,500 tons South Korea was able to acquire would be enough to provide for 20% of South Korea's domestic graphite consumption. Given North Korea's considerably smaller economy, it's possible that this one mine is capable of providing for all or nearly all of the country's needs (graphite is mined in smaller quantities at other sites).

The deal with South Korea eventually collapsed and production at the mine fell further following new rounds of sanctions. This decline can be seen in satellite images of the last few years that show water building up in the open pit mine and the surface of the waste pond drying and showing signs of agricultural activity within.

At least six other major deposits are known to exist in North Korea and in 2011 the National Defense Commission's Resources Development Corporation agreed to explore graphite deposits in three locations within South Hwanghae Province in cooperation with Chinese firms.

Hyesan Youth Copper Mine (41°21'51.84"N 128° 9'31.68"E)

Copper is one of the most useful and indispensable elements there is. From shell casings to ships, a military can't exist without copper.

North Korea has several copper deposits, but its largest copper mine is in Hyesan, near the border with China. Copper's utility also makes its export a prime source of foreign currency. To that end, operations at Hyesan have occasionally been carried out jointly with Chinese companies such as Wanxiang Resources Limited Company in 2007.

First explored in the 1960s, today the mining complex spans several kilometers and is estimated to have an annual capacity of 50,000-70,000 tonnes of copper concentrate. However, flooding, electricity shortages, sanctions, and COVID-19 have caused substantial problems with the mine over the years, and it has never operated at full capacity.

The construction of the nearby Samsu Hydroelectric Dam resulted in the mine being flooded in 2007 as water forced its way through fissures in the surrounding geology. The government spent $8.2 million in the first year after the flood draining and repairing the mine.

More recently, the border closures due to COVID-19 cut off nearly all internal trade, and production at the mine plummeted. While this obviously harms North Korea's economy, limited activity at the mine continues and the extracted copper can still be used for domestic and military requirements.

Susan Titanium Mine (38°57'52.03"N 125°21'42.77"E)

Titanium is a lightweight and durable metal that is used in jet engines, submarines, armor plating, missile components, abrasives, and has many other uses.

The Susan Titanium Mine in Kangso, Nampo is estimated to hold at least 20 million tons of titanium dioxide in reserves. As North Korea seeks to modernize its military and manufacture more advanced vehicles and weapon systems, having domestic titanium supplies and further developing the metallurgical technologies needed to properly exploit titanium's properties will become increasingly important.

A small mine has existed on the site since at least the 1980s, but it was enlarged and modernized in the early 2010s. As North Korea rarely releases official figure of its mining operations, activity at the mine can be tracked through monitoring the growth of its tailings reservoir. In 2011 it covered 12.2 hectares and by 2021 it had more than doubled to 25 hectares in area and was several meters deeper.

Onjinsan Gold Region (38°49'47.48"N 126°26'49.85"E)

This is a name I've given the area surrounding Mount Onjin in North Hwanghae Province that has several gold mines within 10 km of the mountain's summit. Taken together, this is one the largest gold producing regions in North Korea, and it has some of the largest gold reserves in the world.

The two primary mines are the Holdong mining complex (38°52'8.88"N 126°27'31.21"E) and the Namjong mine (38°48'17.46"N 126°21'48.00"E). The area, Holdong in particular, has been a gold mining center since 1893 and has a capacity of at least 2 tons of pure gold a year.

Through imagery we can tell that the mines use the cyanidation process whereby ore is soaked is cyanide which then concentrates the microscopic gold particles into a more easily recoverable form.

Although gold is used in electronics, its main value is in its ability to bring in foreign currency, enabling North Korea to fund its activities. Gold can also be very hard to trace once melted and sold into the global gold market, making it an important vehicle for illicit economic activity.

Unlike some other minerals, gold mining falls under tighter government regulation and the military plays a role in its extraction and export. The secretive Office 39, which helps to finance everything from luxury cars to missiles, is also alleged to play a role in gold production and illegal exports.

Iron Mining

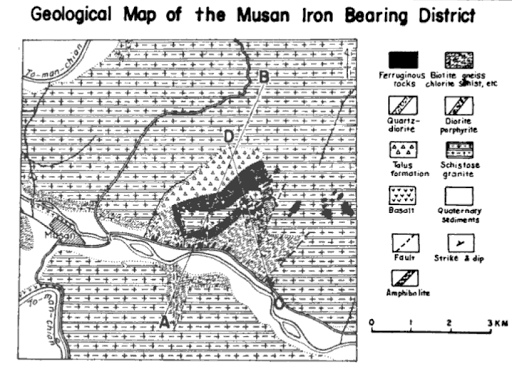

Like copper, iron is indispensable. Tanks, ships, artillery, and everything in between relies on iron and two of the largest iron mines in the country are at Musan and Unryul.

The Musan Iron Mine holds one of the largest iron reserves in east Asia with 1.5 billion tons of ore that is currently economically recoverable and least 7 billion tons in proven reserves.

Like the rest of North Korea's mining sector, Musan has experienced the ups and downs related to economic downturns, famine, and poor economic policies, but it has remained a keystone in the country's industrial capacity and continues to provide around a million tonnes of ore each year.

Unryul Iron Mine (38°35'21.59"N 125° 8'46.47"E), also spelled Ullul, is another large iron mine. This one is located on the country's west coast 40 km northwest of the city of Sinchon.

The large open-pit mine is 2.7 km long and overburden is taken via a 4-km long conveyor belt to the sea where, over many years, it has helped to build up sea walls for a large land reclamation project.

A port was constructed at the conveyor terminus in 2013-2014 for fishing vessels and as part of local aquaculture development. The port and associated facilities are powered by 15,700 sq. m. of solar panels and a wind turbine, making it one of the largest renewable energy sites in the country.

Tungsten

Tungsten's hardness and temperature-resistant properties give it many uses from armor-piercing rounds to use in rockets and airplanes. It can also be used in the protective shells around nuclear warheads.

Both the Man-nyon Mine (38°55'38.29"N 126°57'47.92"E) and Mandok Mine (40°36'55.88"N 128°33'45.41"E) extract wolframite, the main ore-bearing mineral for tungsten.

Man-nyon is an underground mine with a series of mine faces that are interconnected and accessed through a tunnel system. The full area of mining activity extends across approximately 10 sq. km., with small exploratory mines spread further out.

At Mandok, iron is also extracted. Water runoff from the mines is stained with the oxidized metal, noticeably staining the rivers a rusty color for over 20 kilometers.

The United States Geological Survey estimated that North Korea produced 1,410 tonnes of tungsten concentrate in 2018. At 65% purity, that would yield 916 tonnes of elemental tungsten - placing North Korea in the top 10 producing countries globally. This is considerably more than 2014-16, when only 70 tonnes was estimated to have been produced each year. The reason for such a dramatic increase is not explained in the report.

Komdok Mining Region

Komdok is one of the largest mining regions in North Korea and produces everything from magnesite to lead to zinc to cobalt - cobalt being used in temperature-resistant alloys, stealth technology, and ammunition.

The region holds one of the largest magnesite deposits in the world, with an estimate 2.3 billion tonnes in reserve. Magnesite can be alloyed with other metals for a range of products including aircraft parts, rocket nozzles, optics, and batteries.

The dozen or so mines in the Puktae River valley which runs through the Komdok region are also sources of lead, zinc, cobalt, and small amounts of other minerals necessary to the defense industry.

Typhoon Maysak in 2020 hit the area and caused substantial flooding. In response, Kim Jong Un ordered that 2,300 housing units be immediately constructed and that the transportation network be upgraded to facilitate future investments in the region.

Calling Komdok a "major artery of the national economy", Kim outlined his second phase for the area in order to build it into "the world's best mining city". This attention underscores Komdok's strategic importance.

March 5 Youth Mine (41°42'19.97"N 126°49'10.99"E)

Molybdenum is used in the production of 80% of the world's steel and forms strong carbide alloys making it a needed element for creating high-temperature metals and 'superalloys'. It is used in the aerospace industry, missiles, and metal armors.

At least three mines are known to produce molybdenum but the March 5 Youth Mine in the village of Hoha-ri has North Korea's newest molybdenum ore processing facility and it was visited by Kim Jong Il.

According to Radio Free Asia, North Korea has been stockpiling mined molybdenum in anticipation of resumed trade with China and in the hopes that molybdenum prices will have spiked by then. One organization involved in North Korea's molybdenum trade is the military-affiliated trading company Kangsung.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters: Alex Kleinman, Amanda Oh, Donald Pierce, GreatPoppo, Henry Popkes, Joel Parish, John Pike, Kbechs87, Russ Johnson, Squadfan, and ZS.