Workers cleaning rooftop solar panels on a building in Pyongyang. Image: KCNA, 2019

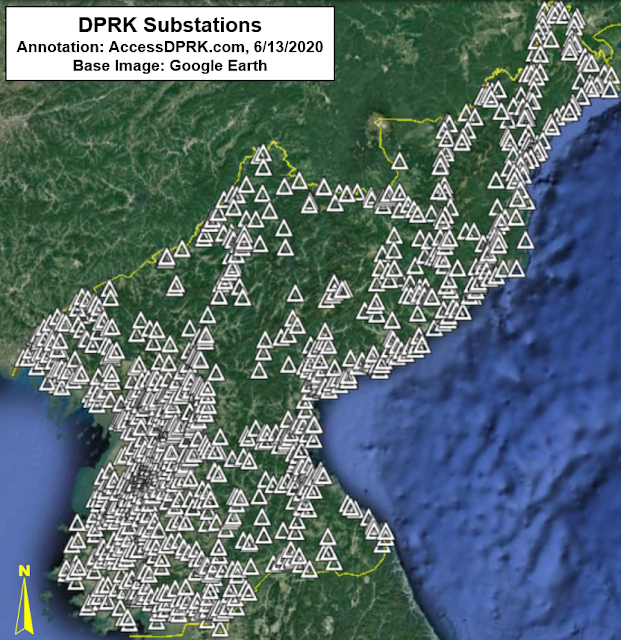

North Korea is a land full of bucolic views and industrious people. It also suffers from river pollution, air pollution in Pyongyang, and a never-ending shortage of electricity, which hampers every aspect of domestic and industrial life.

Most countries have embarked on developing a green economy and a green energy supply to fuel economic growth. This has been spurred on by the dangers of climate change and the realization that easily accessible fossil fuels are getting harder and harder to find.

To address climate change, every country on earth (including North Korea) signed the Paris Agreement. Long seen as an outsider to the global community, North Korea is still a signatory, whereas the United States has pulled out.

And to address ever growing energy needs, the world has heavily invested in renewable energy sources. Since 2000-2001, global

consumption of traditional fuels fell from 12,500 TWh to 10,895 TWh (as of 2017). In the same time frame, consumption of renewables like hydroelectric, solar, and wind more than doubled from 2,817 TWh to 6,232 TWh.

While North Korea is technically classified as an industrialized country, most of the people live in poor economic conditions. Other countries face similar problems. They have a growing population and a need for more electricity (but at levels that still fall far behind western countries). At the same time, they often lack the funds to build advanced and cleaner versions of coal plants which can cost many billions of dollars, and they lack the healthcare infrastructure needed to address the illnesses associated with mining and burning fossil fuels.

And this is where the drive to fight climate change and the drive to improve energy and economic conditions merge. In per capita terms of "kilograms of oil equivalent" North Korean's use approximately 1/15th as much energy as Americans. This means fewer TVs and energy intensive refrigerators. It means that homes outside of major cities may only have a radio, a few light bulbs, and an electric rice cooker. Thus, these homes don't require huge sums of electricity, so many are turning to solar and going "

off the grid".

After generations of focusing on massive energy producing projects, North Korea seems to be switching tactics and creating a patchwork energy grid. Large coal and hydroelectric plants to service primary industry and the major cities, and smaller hydroelectric dams along with limited solar and wind to support less populated areas. As for the individual, they're also getting into the act as mentioned above. This network has the potential to greatly ease the country's electricity problems as well as address matters of climate change.

North Korea's behavior isn't only changing how it gets electricity, but it is also tackling longstanding problems with deforestation, and the floods and landslides they bring. Combating this problem will not only affect the environment but will also help alleviate food shortages and enable the government to spend money elsewhere, instead of rebuilding cities after

major floods.

Wind Power

Two wind turbines at Ongjin, dated Nov. 25, 2019.

One of the oldest wind farms in North Korea is near the Ongjin Airfield and consists of two separate groups of two wind turbines. Both sites have existed since at least 2009.

In 2009, the Korean Central News Agency

reported that thousands of home-use wind turbines had been installed around the country. There is some photographic evidence for this, but little satellite-based support. Unfortunately, these turbines are indeed very small and may not be visible in most commercial satellite imagery, so it is difficult to independently gauge just how widespread home-based installations are.

There are at least four other wind farms in North Korea. The newest installation I could find is in the rebuilt city of Samjiyon. There is also a small solar farm, and both are located at the top of the ski resort.

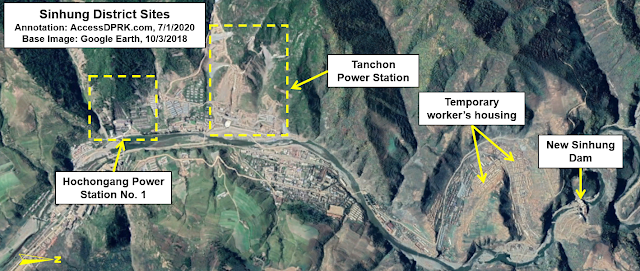

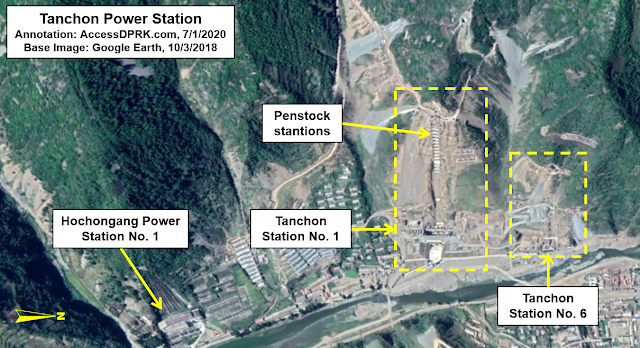

Changes in hydroelectricity production

North Korea has its share of relatively large hydroelectric dams, with some dating to the Japanese colonial era. Several run along the Yalu River at their northern border and others are located inland like the

Songwon Dam and Ryesonggang Youth Power Station No. 1. However, North Korea's attempts to build large hydroelectric dams have run into many problems and delayed construction. The final results rarely yielding the levels of electricity generation expected. Other smaller, older hydroelectric facilities (like along the Taedong River) have also fallen short of their generating capacity and are now primarily used during planting and harvest seasons to assist in irrigation and powering up agricultural facilities.

In the last decade, Kim Jong Un has been carrying out "new" agendas that were initiated by his father, and shifted the country's hydroelectric plans toward more small and medium-sized hydroelectric facilities that can also better control river flows and water supplies for irrigation.

These projects include multiple dams along the Ryesong River and the

Huichon series along the Chongchon River. There was also an effort to build scores of "low-head" power generating stations that pre-dates Kim Jong Un's efforts but have proven the effectiveness of smaller dams and generating sites in adding up to lots of energy generation while not requiring vast sums of material, and they can be built in less than optimal river systems (located primarily in South Hamgyong Province).

One of the most recent hydroelectric series to be completed is the

Paektusan Hero Youth Power Stations. Other series that Kim Jong Un managed to complete have been the Wonsan People-Army Power Stations and the Wonsan Youth Power Stations which have six generating plants between them.

Combined facilities

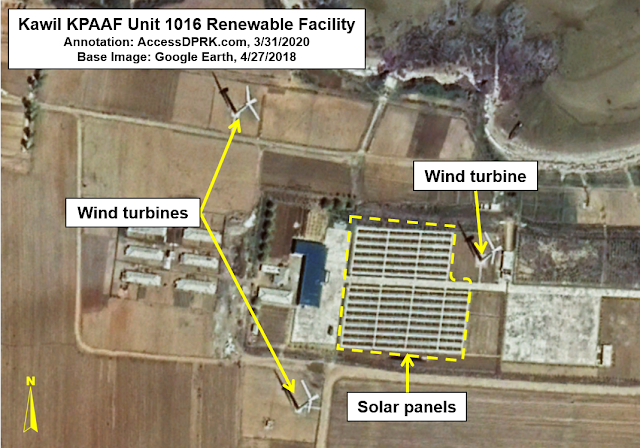

A great example of the push toward renewables is the KPA Air Force Unit 1016 combined wind-solar farm, located near Kawil, S. Hwanghae Province. Initially it was just a wind farm with three medium-sized turbines with construction beginning in 2010. In 2015, a 5,545 sq. meter solar farm was added to the site. It is the largest combined facility in the country.

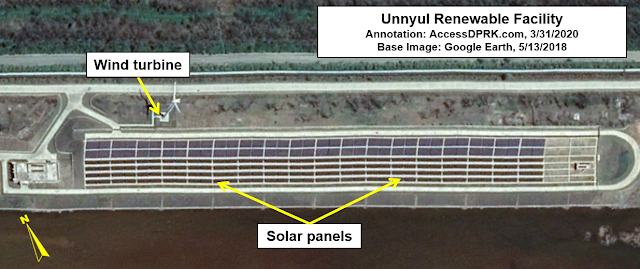

A second facility is located along the 4.6 km long conveyor system of the Unnyul mine and associated land reclamation project. This facility only has a single wind turbine, but its solar farm is larger than Kawil's at a little over 18,000 sq. m. Primary construction was carried out from 2015 to 2016, and the site powers eight apartment blocks and a dozen or so other buildings, as well as an industrial site.

Reforestation efforts

Before and after images of tree replanting efforts from 2003 and 2018. In the bottom image you can rows of planted trees in the formerly bare hillside.

Deforestation has been recognized as a major contributing factor to flooding and the 1990s famine by the regime since the days of Kim Jong Il. Denuded hillsides can't hold on to soil, making landslides more common and increases runoff into rivers - choking them and killing fish in the process. Fewer trees mean an increase in top soil depletion and airborne dust. And fewer trees mean a lack of needed firewood

and decreases the richness of local ecosystems. People rely on native herbs, fungus, and small animals for food and commerce, and without forests, those ecosystems and opportunities disappear.

Between 1990 and 2005, North Korea lost nearly a

quarter of its forest cover and it has become a major problem. While the country is still experiencing a net loss of tree cover, there is now an ongoing effort to replant trees.

In 2015 Kim Jong Un gave a

speech on reforestation efforts. In his speech he recognized that uncontrolled deforestation has been ongoing, that there has been a lack of preventative measures to stop forest fires, and that "

as the mountains are sparsely wooded, even a slightly heavy rain in the rainy season causes flooding and landslides and rivers dry up in the dry season; this greatly hinders

conducting economic construction and improving people's standard of living..."

Tree planting efforts date to 1946 with the annual "Tree Planting Day" each March, but there is little evidence that these single day events did much to ameliorate the situation during the rapid deforestation that occurred in the 1990s or to replant meaningful numbers of trees since then. Kim Jong Un's critical recognition of the problem, however, is a sign that the state is going to take the problem of deforestation and wildfires much more seriously, especially considering the mix of both extreme drought and damaging floods the country faces - which tree cover levels can play a major role in.

In Kim's 2015 speech he gave a ten-year goal to reforest the country's mountains. Efforts to achieve this goal includes the establishment of scores of tree nurseries across the country that can, theoretically, produce

20-25 million trees annually. The regime has also begun to crackdown on the illegal private farms that dot the hillsides and have played a role in deforestation and soil degradation.

Nurseries have indeed been constructed. How well those trees are later transplanted and able to mature is left to be seen.

Conclusion

As international relations expert Benjamin Habib

has said,

"The North Korean government would appear to have a compelling prima facie self-interest in participating in the global climate change mitigation and adaptation project centered on the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)" as growing environmental issues can threaten the survival of the regime.

Indeed, a 2019 report by

NK News pointed out that climate change threatens the very existence of the northern port city of Sinuiju by 2050.

Unfortunately, the actions taken have been a patchwork of activity, generally lacking coordination or broad national action. Additionally, the main focus doesn’t necessarily seem to be creating a better environment for the people, but rather these changes are pragmatic decisions to help accomplish industrial and military goals, that happen to have other benefits.

While investing in renewable energy sources, allowing individuals to go their own way regarding solar water heaters, etc., are obviously beneficial, the problem of pollution still exists and there are few overt plans to change that reality.

Though new trees help stabilize the ground and protects farmland, hundreds and hundreds of acres of farmland are situated on highly polluted soil, such as on former coal ash ponds, leading to contaminated food. Two large examples of this can be seen at the Pukchang Thermal Power Plant and adjacent to the Namhung Youth Chemical Complex near the city of Anju.

And while mixing up the country's energy portfolio with renewables will have an impact, the country's coal-plants still spew out tons of air pollution and release

toxins into rivers. North Korea's

nuclear development and industrial sectors likewise negatively impact large swathes of the nation and the people who call it home.

Even actions taken by the government to increase the food supply by reclaiming tidal flats and converting them into farmland will not be sustainable without mitigation efforts, as sea levels rise and saltwater contaminates ground water. And if the West Sea Barrage comes under threat, Pyongyang itself could suffer the direct effects of sea level rise in the future.

As the effects of global warming become more pronounced, the Kim government must take a serious look at how they can accomplish their more immediate goals of militarization and creating an adequate energy supply in the light of what impact they may have on the overall health of the people, and the state's role in either contributing to or helping to limit climate change.

Countries with major coastal cities and those with limited economic power face the greatest challenge. As laudable as these changes are, without taking the threat more seriously and without creating a more open diplomatic environment to allow for future international aid, North Korea is unlikely to achieve energy independence and may be very hard hit by the growing realities of climate change.

I would like to thank my current

Patreon supporters: Amanda O., GreatPoppo, Kbechs87, Planefag, Russ Johnson, and Travis Murdock.

--Jacob Bogle, 4/4/2020

AccessDPRK.com

JacobBogle.com

Facebook.com/accessdprk

Twitter.com/JacobBogle