I've written about the DMZ before, discussing how it has changed over the last decade or so. But now I would like to go into greater detail about its actual functionality - how it's laid out, what kind of defenses exist, and what kind of offensive capabilities are contained within.

The DMZ (demilitarized zone) is defined as a buffer zone between the two Koreas. It extends for 250 km across the peninsula and is approximately 4 km wide. However, the only fully defined part of the DMZ is the "military demarcation line" (MDL) which is the de facto land border - the actual line dividing the countries. On either side of that line is the buffer zone, which happens to be the most militarized area in the world.

In practice, the part of the DMZ that is actually devoid of any soldiers varies considerably in width. And the width of the various integrated defenses on either side of that no-man's land also varies. For the purposes of the AccessDPRK maps and this blog, I classify military sites within 5 km of the military demarcation line on North Korea's side as "the DMZ", because within that area lies an almost uninterrupted web of observation posts, storage sites, bases, artillery positions, and other sites that clearly form a unified military infrastructure.

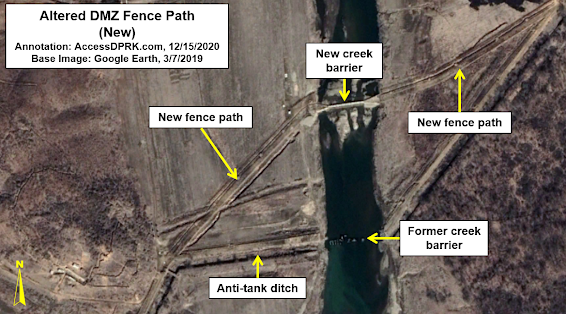

What became the DMZ largely reflects the battlelines as they existed in 1953. On the North Korean side, relics of the Korean War can still be seen including cratered hillsides and trench remains. And many of the extant static defenses such as anti-tank ditches and dragon's teeth can be traced to the 1960s and 1970s. Although some of these sites have been heavily impacted by erosion and would offer little practical defense today others still exist in good condition, and the manned instillations along the DMZ are routinely maintained and hundreds of new sites have been constructed over the years.

With thousands of manned positions and hundreds of kilometers worth of trenches and anti-tank ditches, the DMZ is a considerable defensive line. Because of this complicated layout, I want to try and "dissect" it piece by piece.

One last note, the images used are chosen because they provide a clear view of the site being looked at. Image quality can vary a lot, so the most recent image may not display the best visuals. Perhaps there's cloud cover, it's too dark, too bright, at the wrong angle, etc. However, if an image I've chosen does happen to be from several years ago, that site still looks the same as it does in recent images. The older image is simply "prettier" and makes it easier to show the necessary details.

Order of Battle

The exact details of North Korea's order of battle aren't fully known publicly, but what is known would still take up more room than I have for this post. However, the Ministry of Defense (formerly the Ministry of the People's Armed Forces) deploys roughly 70% of its active duty ground forces south of the Pyongyang-Wonsan line that lies roughly 120 km north of the DMZ. A substantial portion of the Navy and Air Force is also positioned within that area as are five short-to-medium-range ballistic missile bases.

Some of the details include that the DMZ is manned by members of the Korean People's Army I, II, IV, and V Corps according to Joseph Bermudez's book The Armed Forces of North Korea. Their operations are under the command of the Third Department of the General Staff Department's Operations Bureau which is part of the Ministry of Defense and subordinate to the State Affairs Commission.

These Corps represent the First Echelon of KPA Ground Forces and defend the DMZ and the areas immediately behind it. The Second Echelon of forces (which include the 820th Tank Corps and 815th Mechanized Corps) are tasked with defending the main invasion avenues into North Korean territory on the approaches to Pyongyang.

Each Corps will have their own specific makeup but, in general, they will consist of light infantry brigades, artillery brigades, tank brigades, sniper units, anti-tank units, electronic warfare/SIGINT units, reconnaissance units, communication and transport units, engineering regiments, and others. They will also have units assigned to chemical warfare and nuclear defense (although not nuclear weapons).

Special Operations Forces are also deployed along the DMZ and are under the command of the Reconnaissance Bureau and Light Infantry Training Guidance Bureau.

The 3rd Air Division is responsible for protecting the south of the country and the DMZ. Immediate aerial support could be provided by the eight closest primary airfields and would include support from SU-25s, MiG-17s, MiG-29s, An-2 biplanes, and MD-500 and Mil Mi-2 helicopters (among other manned aircraft and UAVs). There are also 29 additional runways, landing strips, heliports, and emergency runways within 100 km of the DMZ. And, of course, fighter and bomber aircraft could be sent from any of the airfields in North Korea, not just the ones in closest proximity.

Ballistic missiles under the control of the Strategic Rocket Forces would be used to destroy key targets within South Korea and to help Special Operations Forces disrupt and push back an invasion by South Korea by opening up a "second front".

Invasion Routes

Several portions of the DMZ serve as natural invasion routes that could be used by either side to invade the other. From a defensive perspective, the North Korean fortifications would stall an invasion coming from the South that would likely be funneled through the low and flat terrain between Kaesong to Pyongyang (an invasion route that has been used historically for over a thousand years), north toward the city of Koksan which would take out several important infrastructure sites and also grant access to Pyongyang, from the South Korean city of Cheorwon to North Korea's Sepo and through a valley into Wonsan (cutting Kangwon Province in two), and lastly through the narrow plain that exists along nearly the entire east coast (also an historic invasion route)

To help slow down a ground invasion, a network of unmanned static defenses has been constructed over the decades. Many have been impacted by time and erosion, but the sheer number and breadth of them means that they remain an obstacle that would have to be taken into consideration.

Unmanned Anti-invasion Defenses

Except for a mountainous border region in Kangwon Province where there is only one line of fencing, the DMZ is protected by two lines of electric fencing. Each line of fencing (separated by 0.5-1 km) consists of two parallel rows of fence. The fence lines are dotted with around 10,000 foxholes in total. There are at least 99 gates in the second (interior) fence line as well that allows KPA personnel access to the first (forward) fence, observation posts, and foxholes.

In low-lying areas like valleys and plains there are anti-tank ditches, anti-tank walls, and rows of dragon's teeth (pyramidal shaped concrete blocks that can't be driven over). I've located over 80 km of anti-tank ditches/walls and 56 sites where dragon's teeth are present within the 5 km designated area.

Roads in and around the DMZ are not paved but are simply winding dirt tracks. This is actually part of the overall defensive strategy as such roads force vehicles to slow down and do not provide direct routes further into North Korean territory. These roads are protected by large anti-tank blocks/roadblocks that can be knocked over into the roadway and block vehicles from passing until the blocks can be removed. There are around 170 of these sites within 5 km of the MDL and dozens more outside of the immediate area.

Manned Defenses

If one were to look at a cross-section of the DMZ, its layout would generally follow this pattern (moving north from the MDL): fence #1, observation posts (ops), forward posts, fence #2, additional posts (entrenched positions, fire teams, artillery), and then medium- and long-range artillery positions such as HARTS.

Back from the second fence are also munitions storage sites, larger bases/units, vehicle facilities, and other supporting instillations that are interspersed throughout.

Immediately behind the first fence, spaced anywhere from 0.5 to 2 km apart, are 183 "forward posts" which are the forwardmost manned positions capable of shooting back at an enemy. These posts vary in size but are surrounded by trenches and include their own observation sites as well as fire control centers, fire teams, and can also have entrenchments for short-range artillery and mortars.

There are 69 HARTS positions within the 5 km area. Between 2009 and 2017, a total of 126 new HARTS and hardened Multiple Launch Rocket System emplacements were constructed within range of the DMZ and can hit targets as far away as Seoul. They represent 20.7% of all HARTS located within 100 km.

Mortar emplacements can exist as part of a larger fortified site or, as in the example above, as stand-alone sites. As is often the case with all types of artillery across the DMZ, this mortar line exists on the downward (back) slope of a hill providing defilade protection against a counterattack because its position is not in direct line of sight but obscured by the hill.

There are also dozens of empty prepared positions along the DMZ for artillery. Some sit in the open and others have small bunkers for protection. These are reserve sites that allow artillery pieces to be moved in from elsewhere and from site to site to add additional fire power in a specific region as needed, but whose destruction wouldn't significantly degrade North Korea's capabilities since they can quickly be repaired or simply abandoned, and the artillery moved to another site.

There are around 800 fortified positions (including artillery) and rear support bases that lie 1-2 km behind the second row of fencing. Excluding artillery sites, these bases tend to be small (only a few buildings) and may only have specific functions like billeting troops, providing vehicle storage and maintenance, storing weapons and other equipment, serving as command and communication centers, and some will include field hospitals.

The DMZ is filled with storage sites, from the underground facilities at HARTS to munitions bunkers at mortar lines to partially underground cellars at hilltop bases. But there are also more traditional storage igloos (or bunkers) that dot the landscape.

The storage bunkers are relatively small, with an interior space of no more than 50 sq. m., and consist of a concrete box that has been positioned within a berm or other revetment for safety. Some are located alone as a single structure while others are clustered together in groups of ten or more bunkers.

Between bases, forward posts, observation sites, HARTS, mortar lines, gates, and other sites, there are at least 1,700 manned facilities within 5 km of the MDL in the AccessDPRK 2021 map, but precisely identifying and classifying the locations along the DMZ isn't exactly straightforward and the number of locations could be higher depending on how they're classified/organized.

For aerial defense, not only does North Korea have the aforementioned airbases within 100 km of the DMZ, but there are also eight surface-to-air missile batteries that form a line across the peninsula and are within 50 km of the military demarcation line, and a further ten SAM batteries are within 100 km along with several other permanent installations that can be used for mobile SAM systems.

There are also around 200 shorter-range anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) batteries within 100 km that can attack ROK/US aircraft that try to penetrate into North Korea; although, their effectiveness against modern jets would likely be minimal as most aircraft can fly above the range of AAA systems and may never be forced to come within range of their guns.

Final Thoughts

In the event that South Korea were to launch an attack, North Korea's response wouldn't only be to hold off the invasion but would most likely trigger a counterattack to capture Seoul before the United States could transport more troops and equipment from bases in Japan and Guam. While any attempt to hold Seoul would fail, the battle for the city (no matter how temporary) would result in tremendous civilian casualties. North Korea could unleash a barrage of chemical weapons on the city, and it could use long range ballistic missiles to knock out US capacity further afield by attacking Guam, slowing any allied response.

It is this terrifying risk of Seoul, a city of 10 million, being bombed into oblivion and the severe disruption to global trade that has held off the US and South Korea from ever preemptively attacking North Korea's nuclear and missile sites or assassinating a Kim.

Although technology has advanced and a concerted allied attack on DMZ positions could destroy most North Korean positions within 72 hours, Pyongyang would follow any attack with missiles fired from bases further inland, some deep within mountain ranges. Complicating matters even more is the fact that the US does not have confidence in its ability to take out all of North Korea's hardened positions and their mobile ballistic missile forces before North Korea could fire off a nuclear weapon.

And so, the DMZ - for all of its outdated dragon's teeth and Soviet-era artillery - remains an incredibly dangerous tripwire that could trigger a war no one genuinely wins. The threat of a conventional bombardment of Seoul from the DMZ bought North Korea the time to build a credible nuclear deterrent, and now that deterrent has made the risk of even a conventional conflict along the DMZ too costly.

In the meantime, an ever-advancing arms race continues and the rhetoric coming from either side of no man's land suggests the DMZ will remain a scar across Korea for years to come. As I have shown in previous posts, the DMZ isn't unchanging. And with no clear path toward peace, let alone reunification, it's important for the world to keep an eye on this narrow strip of land that serves as the most militarized demilitarized zone in the world.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters: Alex Kleinman, Amanda Oh, Donald Pierce, GreatPoppo, Joel Parish, John Pike, JuneBug, Kbechs87, Russ Johnson, and Squadfan.