Ever since the mass defections and rise in illegal trade caused by the 1990s famine, North Korea has tightened its grip on border security with increasing severity, but its northern border was still far from impenetrable.

Despite fences and guard patrols, along with inhospitable terrain and weather on both sides of the Yalu and Tumen rivers, plus China's repatriation policies, total defections could reach several thousand each year. While most defectors remain in China in hiding, between 1,000 and 2,000 would make it to South Korea annually since about 2001.

But as the COVID pandemic spread, North Korea was not only faced with a possible existential threat due to the poor state of the country's healthcare system, but it was also faced with an opportunity - to use the pandemic as an excuse to finally (and completely) close down the border.

In the intervening four years, the physical barriers associated with the "border wall" were built, altered, and now appear to be undergoing a final series of changes.

In this article, I will lay out the development and current state of North Korea's anti-pandemic border measures now that the threat of the pandemic has waned, and as Pyongyang seeks to at least partially reopen its borders.

3D render of a section of renovated border fence. This section features a levee, a double-row of fencing, guard posts, and a border guard garrison is in the background (right). Created by

Nathan J. Hunt for AccessDPRK.

As far as I'm aware, I was the first person to note (with the aid of satellite imagery) that North Korea was increasing its border security with a Spotlight Report published by AllSource Analysis back in April 2021.

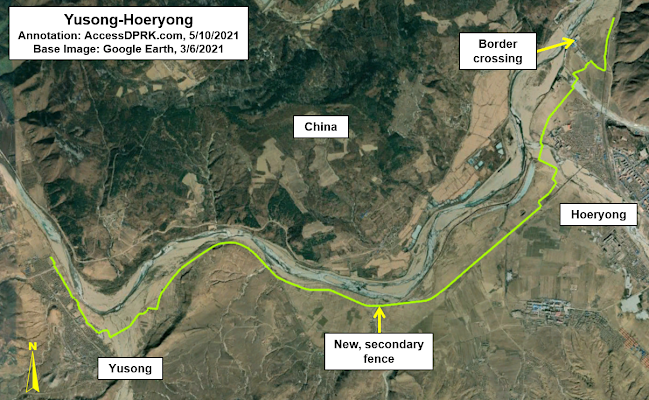

The report highlighted changes around the border town of Hoeryong, particularly noting an increase in the number of guard posts and the now ubiquitous primary and secondary lines of fencing.

Chronologically, however, one of the earliest examples of improved security following the border's closure in January 2020, was the addition of guard posts in Ryongchon County (south of Sinuiju) in September 2020.

Location of new guard posts built in 2020 along a section of older border fence in Ryongchon.

However, according to DailyNK reporting, the order to build a new border fence across the entire border wasn't issued by Kim Jong Un until February 2021.

The addition of new guard posts may have been a separate order followed by a new (Feb. 2021) order to build the border fence, or perhaps the earliest order may not yet have come to light. Regardless, the timeline of increased border security was not uniform, with some areas undergoing construction sooner and others delayed. But by 2021, work was underway along the full North Korean border with China and Russia.

As mentioned, the first activity seen was the installation of thousands of small guard posts. Most were along the existing border fences, but some were placed in the middle of fields or atop river levees. In total, I have estimated that up to 15,000 guard posts dotted the landscape at the height of the pandemic.

Following the installation of numerous guard posts, secondary fence was then constructed behind the main border fence. The secondary fence was located anywhere from just a few meters behind the main fence to several hundred meters behind, and it cut through agricultural fields, forests, spanned rivers, and even incorporated the boundaries of factories and houses.

This secondary fence, based on a range of tourist photographs taken from the Chinese side of the border, was built out of either wood or reeds, depending on the raw materials available in each locality.

Annotated photo of the DPRK border at Namyang showing the main border fence and the secondary fence made out of reeds. Annotations by AccessDPRK. Photograph comes from Weibo, March 2023.

To accomplish the work, construction units logged local forests and built temporary work camps in multiple locations along the border.

Area of interest near Chang-ni in 2020, prior to logging.

Area of interest showing logging activities in 2022.

Timber piles for fence construction in Chunggang County, 2022.

Elsewhere, logs being staged for use in fence construction can be seen. In the above example, that area had simply been empty previously. No logging or storage activity existed prior to this event.

The work camps, as seen below, are standard for any large-scale construction project such as at the major residential projects underway in Pyongyang.

One of multiple temporary, small worker's camps along the Taehongdan section of the Sino-DPRK border.

One of the temporary worker's camps in Musan.

Given the logistics of building a border fence across more than 1,000 km of highly variable terrain, instead of having a single centralized worker's camp, the camps (with their housing, workshops, and other facilities) are dispersed; with dozens of them along the border, each housing only few dozen to a few hundred workers.

Worker's camp near Onsong. Numerous small buildings can be seen in October 2022.

The Onsong camp had been removed by May 2023 and the meandering secondary fence completed.

Following the addition of guard posts to tighten security and the wooden secondary fence that served to cut off access to the areas under construction, any original border fencing was then demolished section by section.

The next steps taken were to reenforce, rebuild, or newly construct flood barriers in places prone to flooding, and then building the new fence on top of those levees - with each province (and likely each county) responsible for providing most of the manpower and materials needed within their jurisdiction.

On a bend of the Tumen River, 2 km away from the Onsong worker's camp, a new levee was under construction in 2022.

By May 2023, the levee was largely completed, and the new electrified fence was placed on top. However, some soil grading activity was still ongoing.

In at least one area, in Rason, a new quarry was opened to provide the materials needed for local levees.

Rason quarry, with both the new main fence and secondary fence visible.

New fences were also constructed on hills and mountainsides, areas that were often left poorly controlled prior to COVID and that served as routes of defection.

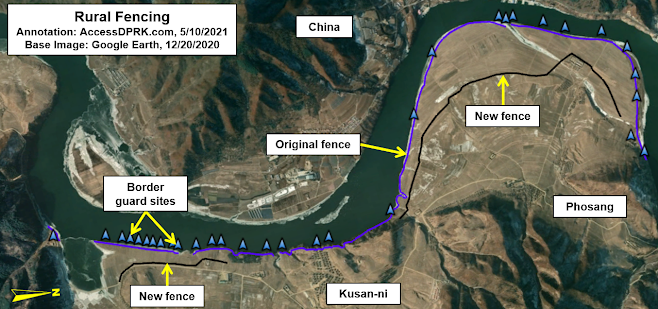

The previous border fence was just a single row of barbed-wire fencing with guard posts that were only concentrated near populated areas and areas where defections were less physically difficult (open fields, narrow parts of rivers, etc.) Guard posts were often 1 km apart or even farther, and the wide reservoirs along the Yalu lacked fencing in general.

The main border fence now comprises two rows of tall fence, allegedly electrified, with a patrol road along it. And the secondary fence appears to have become a permanent part of the system as well.

Guard posts are considerably closer together and can be found along the entire length of the border - even in remote areas. Guard posts are positioned on both the main and secondary fences. Fencing was also added to the previously unprotected reservoirs (such as the Sup'ung Reservoir) and electronic surveillance infrastructure was improved.

Construction of the new fence was carried out by border guards, local labor brigades and, due to the immense manpower requirements, military units from XI Corps (Storm Corps) were also used. However, the same manpower requirements that necessitated the use of the military to help construct the border fence also temporarily drained the readiness of the corps.

After first being fortified with additional guard posts, the fence path in this area was moved further inland to follow an existing road.

Between 2021-2023, fence paths were adjusted to improve local security and as better paths were identified during construction.

Along with the fences and guard posts, over 400 border guard garrisons now dot the landscape. Most of the garrisons existed before COVID and many had already been renovated ca. 2016, but new ones were still constructed, and other changes were made to existing sites.

Example of a border guard garrison.

However, there have been changes to the level of security seen earlier on in the fence's development. What I would describe as being overkill in the number of guard posts (and thus guards needed) has been relaxed, with many redundant positions removed.

Nonetheless, the northern North Korean border has become one of the most well-secured civilian borders in the world. Presently along the northern border are over 400 guard posts, 10,000-13,000 guard posts, and approximately 2,100 km of primary and secondary fencing has been identified by AccessDPRK.

Combined with increased security on the Chinese side of the border and enhancements to the DPRK coastal fence as well, it is unlikely that defection rates will return to previously seen levels anytime soon. (Only 196 made it to South Korea in 2023.)

Animation showing the development of a section of border fence from July 2020 to October 2023.

3D render of the same section of fence with the border guard garrison building shown on the left. Created by

Nathan J. Hunt for AccessDPRK.

Note: if you'd like to learn more about how North Korea's border closure has impacted the lives of average North Koreans, check out this in-depth report from Human Rights Watch which I assisted with.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters who help make all of this possible: Alex Kleinman, Amanda Oh, Donald Pearce, Douglas Martin, David M., Dylan D, Joe Bishop-Henchman, Joel Parish, John Pike, Jonathan J., Kbechs87, Raymond Ha, Russ Johnson, Squadfan, and Yong H.

--Jacob Bogle, 7/23/2024