Downtown area of the reconstructed Samjiyon. Off in the distance is a bronze statue of Kim Il Sung and "revolutionary history" museums at the base of the hill. (KCNA, 2019)

Plenty of people are familiar with Pyongyang and even other major cities in North Korea, but most of the population lives outside of the capital, Wonsan, and Sinuiju. Car ownership is still rare in North Korea, so even in Pyongyang, it doesn't take very long to find yourself on winding, narrow dirt paths. But the layout of streets is only one part to city planning.

The majority of the housing, stores, and schools in my hometown is in an area roughly 5 x 5 miles. That's a city with about 150,000 people. There are 14 North Korean cities with a population of 150,000 or greater. Excluding Pyongyang, the urban areas of those other 13 cities all fit within an area smaller than 5 x 5 miles.

And even Pyongyang, with 2 million people living in the main urban area, only occupies about 67 square miles. That is almost the same area as the federal district of Washington DC, which has a third of Pyongyang's population. This underscores the realities of how densely cities develop when cars aren't the "driving force" vs. how cities grow when vehicle ownership is viewed as a personal imperative. The result of that is North Korea lacks a lot of the urban sprawl that plagues many other countries.

Main urban area of Pyongyang.

Where you place important buildings, markets, or stadiums, it all matters, and it all says something about what the people and government find most important. This is all the more important when you're dealing with a walking and biking population.

City plans place what is important to the regime in the center and then from there follows places that would be important to the people (like small business districts that may have stores, a restaurant or two, and maybe a small hotel). To help us understand the overall city planning fundamentals in North Korea, I am going to detail two county seats, a smaller town, and then an even smaller village.

County seats follow two general layouts. A compact core of civic buildings and monuments around central plaza or a more spread out design where citizens encounter reminders of the state at multiple points throughout the city. The main difference between county seats and provincial capitals is that each provincial capital will also host large, bronze statues of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il. Otherwise they tend to simply be enlarged versions of county seats with more industrial sites, more local businesses, and the occasional university.

Kophung, Chaggang Province is an example of the "compact" design.

As you can see, the main roads of Kophung channel people passed important reminders of regime power like the Juche Study Hall and the Tower of Immortality. The town hall is, of course, centrally located as well. Another thing to note is how far away the marketplace is.

While it's certainly within walking, it has been placed on the outskirts of town, something that is repeated in many of other locations. This is because most markets began as unofficial, even illegal, gatherings of people trading, bartering, buying, and selling. Some would be little more than an open area of ground where people would bring their goods, while others had small tents or other temporary structures placed at the site during the day or two the market was open.

As markets were slowly incorporated into the daily lives of most citizens, they became tolerated and then eventually regulated by the state. This allowed permanent structures to be built and they tended to be built where the informal market was already located - in the outskirts or other less desirable places.

Generally speaking, markets are also located some distance away from any key state symbols (like monuments), as they are somewhat regarded as an ideological stain (albeit one to accept). You can't have a blazing example of capitalism and individual freedom next to a monument to the communist "Sun of Mankind", Kim Il Sung.

In this close-up image, you can see that the line-of-sight from any direction you come, lands on the Tower of Immortality. These were first erected following the death of Kim Il Sung as monuments to his life and to reflect that his spirit will always remain. Indeed, Kim Il Sung is legally the "Eternal President" of the DPRK. The inscriptions on the towers were changed to include Kim Jong Il after he died. He is the "eternal" General Secretary of the Korean Workers' Party.

Additionally, every county seat (and provincial capital) have joint murals of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il. During my 2018 survey of the country's monuments, I was able to identify 5,175 Towers and 265 joint murals.

Like elsewhere in the world, cities will usually keep their small industrial sites away from the city center. Many county seats also lack a stadium or dedicated sports field, but they will use the fields at schools. For those that do have a stadium, they are likewise set out away from the urban core.

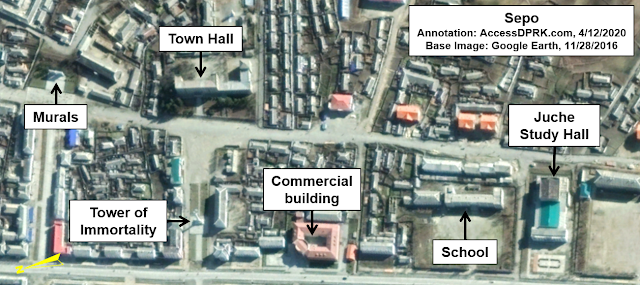

Sepo, Kangwon Province is an example of the "spread out" design.

With the city of Sepo, the regime-focused structures are spread throughout the city, instead of in a single cluster. From the image's perspective, moving north from the train station (which is how most people arrive into town), there is a direct line of sight to the Tower of Immortality, and from there, to the town hall.

If someone travels down either of the main left-to-right roads, the joint murals will be visible at one end and the Juche Study Hall at the other (which happens to be surrounded by two grade schools. One is marked in the above image and the second is marked on the image below).

Every town has at least one "Juche Study Hall", they go by a number of different names including, palace of culture and Kimilsungism-Kimjongilism study hall. These basically play the equivalent role of churches in Europe and the Americas in centuries past. Centrally located, this is where people are required to go multiple times a month (at least) to be indoctrinated in the latest Party orders, to learn about the exploits of the leadership, and to hold "self-criticism" sessions.

Instead of struggling through alcoholism and freely talking about your journey in a safe environment, as in Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, self-criticism sessions could be described as meetings holding each other accountable for "wrong thought". But it goes much further than that. Everyone fails Kim Jong Un. Everyone holds thoughts incompatible with Juche. Everyone didn't try hard enough to study their best or to meet their quotas during work. Everyone fails and everyone is expected to come up with something to confess, whether or not they really did it.

And instead of being supported by their community, they are shouted down or accused by everyone in the group. These sessions can last hours, and defectors have spoken about the emotional trauma they cause.

Hwanggang-ri, N. Hwanghae Province is an example of a smaller town (38°20'16.79"N 126°47'8.90"E)

Hwanggang-ri is a small town with fewer than 2,000 people in the immediate area. It has a single, combined school where the elementary school and high school are within the same complex. From the perspective of this image, to the north of the Tower is the town hall and below the Tower label is a row of four buildings.

Each North Korean town has a medical clinic. Unlike schools or Juche buildings, these clinics don't always have a uniform style that is easily identifiable from satellite images. (Large hospitals are more easily discernible, but they're only in large cities anyway.)

In some places, the clinic is located inside the town hall and in others, a stand-alone building exists for the clinic. These clinics only offer basic health care functions, similar to a walk-in clinic that a pharmacy might have in western countries. They can diagnose a cold, give you something for a fever, stitch up a cut finger, or pop a shoulder back into place. They are not for MRIs or open-heart surgery. And given the state of North Korean healthcare overall, you probably won't find any antibiotics readily available, either.

A town this size is large enough to have a clinic, but whether it's in the town hall or in one of those four buildings, I can't say.

Unphyong-ri, Chaggang Province, is an example of a small village (40°52'51.36"N 125°46'20.17"E)

Even in small villages with only a couple hundred people, where having a separate building for Juche studies doesn't make sense, there is still a Tower, a town hall, and a school nearby. That simple organizational style is repeated in almost every populated place in the country. Only the smallest hamlets lack these things.

In the most rural parts of the country, schools are simple and may require a long walk, but it underscores the importance of basic education. Most students may only receive a limited education, but reading and basic math are fundamental to any functional society.

As we have seen recently with the city of Samjyon, cities can be completely redesigned, demolished, and then rebuilt in the new design on the whim of the country's leadership. And many larger cities have had parts of their cores rebuilt or modernized at the direction of Kim Jong Un and through the national Korean Workers' Party. But local additions must be requested, approved by higher authorities, materials assigned, and then finally the buildings can be constructed. This means that a village might not see a single new home or even a repaired home for many years. Indeed, no new homes are visible in Unphyong-ri since 2009 and only two new homes were built in Hwanggang-ri since 2002.

And as we have seen here, no matter the size of the locale, there will always be a recognizable pattern in the plans of each city and village. They will place regime buildings and monuments in high visibility areas, schools will (often) be nearby, and signs of capitalism will be pushed to the side if possible.

Additional reading

A brief urban history of Pyongyang, North Korea - and how it might develop under capitalism, The Architect's Newspaper, by Dongwoo Yim, Aug. 24, 2017

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters: Amanda O., GreatPoppo, Kbechs87, Planefag, Russ Johnson, and Travis Murdock.

--Jacob Bogle, 4/14/2020

AccessDPRK.com

JacobBogle.com

Facebook.com/accessdprk

Twitter.com/JacobBogle