AccessDPRK's last article examined some of the largest underground facilities in the country. In keeping with the underground theme, I want to take a look at some of the more enigmatic tunnels in North Korea.

Plenty of the country's tunnels are part of factories, missile bases, or nuclear sites, but there are a few tunnels that seem to go nowhere. Maybe they're for storage, maybe they're part of secret escape routes for the Kims, we just don't know what they're really for.

In this article I will examine four of these "tunnels to nowhere" and in doing so, will hopefully shed a little more light on their existence and their nature.

Taenoŭn-san (41°57'34.23"N 128°41'37.13"E)

Google Earth image of vehicle entering the tunnel on Sept. 19, 2019.

The Taenoŭn-san tunnel near the Chinese border is one of the most recent to come to light. It was first mentioned by Nathan Hunt on Twitter on Jan. 20, 2020 but it has never been described through public intelligence channels, and so its purpose remains speculative.

Based on imagery from Landsat, the tunnel was constructed in 2016 but it didn't show up on Google Earth until late 2019 with an image dated Sept. 19, 2019. In that image, a vehicle can be seen entering the tunnel.

It has not been positively identified in the public sphere, but one possibility is that it could be a TEL/MEL with two missile launch canisters. A vehicle can also be seen on an image from Sept. 11, 2021.

The tunnel enters a small mountain from a river valley and has no exit point. The entrance is around 10 meters wide and access comes in the form of a dirt road. The road does not directly lead to any nearby military base. There are also no obvious security measures such as a gatehouse to the entrance or perimeter fence.

This could be, in part, due to its remote location within Ryanggang Province (only 6 km from the Chinese border) making accidental discovery by locals almost impossible as a result of the travel restrictions in place within the country. Joy riding and exploring simply aren't part of the North Korean experience as it is in other countries.

Some theories as to its purpose is that it's a storage site or, perhaps, even part of North Korea's second-strike capacity - allowing the country to hide short-to-medium range ballistic missile TELs/MELs in a hardened site that could withstand an initial strike by an enemy, enabling North Korea to still launch missiles even after the primary launch sites have been destroyed. At this point, it's all speculation.

Although the entrance is 10-meters wide, the state of the access road (a winding dirt path) would prevent the tunnel's use by ultra-large vehicles such as North Korea's giant 11-axl TEL for the Hwasong-17 ICBM.

Pyongyang-Sunan Tunnel (39°11'38.84"N 125°45'13.77"E)

This tunnel is located within the Sunan guyok (district) within the city of Pyongyang. It is less than 1.5 km from the Kim Jong-il Peoples' Security University and is within 5 km of six major military sites including a large storage complex, the Kim Jong-un National Defense University, and the Second Academy of Natural Sciences which is a major missile fabrication facility. Of course, direct association with any of those sites has yet to be ascertained.

Construction on the tunnel began around April 2017 and went through to April/May 2019. The tunnel's entrance is around 11 meters in width. The access road is compacted dirt but that then turns into a paved area ~33 meters long as it approaches the entrance.

Some images have what appears to be framing to hold a tarpaulin or camouflaged netting. On an image dated April 11, 2019, the tunnel looks to be covered by the netting.

The complex also has an access tunnel, likely for maintenance, that's large enough for small vehicles to enter.

There is a spoils pile from the tunnel excavation along the southern side of the road that extends for ~140 meters. It varies in width from 10 meters to as wide as 16 meters. If we use an equal width of 10 meters and give it an assumed height of 3 meters, then the total volume of excavated material can be estimated to be 4,200 m3

This would allow for a tunnel that's around 95 meters long, 11 meters wide, and 4 meters high.

Onsong Tunnel (42°54'47.37"N 129°56'38.90"E)

Google Earth image of the tunnel dated March 10, 2022.

In the village of Ryongnam-ri within Onsong County a tunnel was constructed beginning in late 2017 and it was completed in mid-2019. There's nothing particularly interesting about Ryongnam-ri, especially from a military perspective, yet this tunnel is well protected by a berm and may even have a small blast shield located across from the tunnel opening.

Like the tunnel in Taenoŭn-san, it is 9-10 meters in width, however, no vehicles are visible in the available imagery from Google Earth. If the spoils pile is representative of the majority of the material removed for the tunnel's construction, it's unlikely that it extends more than 100 meters into the hillside.

The tunnel isn't connected to any obvious construction elsewhere in the area and seems to be 'randomly' placed at the rural village. Depending on which direction you travel from the tunnel, it's only 6 to 7 km away from the Chinese border.

Militarily, there's nothing especially interesting about Onsong County. It has a single air-defense site that protects the Wangjaesan Grand Monument and there's a small training base located 6 km northwest of the tunnel. Otherwise, the nearest important military installations are over 50 km to the south.

There does seem to be a fence guarding access to the site, but it is situated next to civilian buildings and is not within a military base, making its purpose more difficult to identify.

Secret Road Tunnel (39°52'2.70"N 126°22'29.58"E)

This last tunnel is the oldest on the list and is, to me, to most unusual.

Located 13 km north of the city of Tokchon, the nearest populated place is a village called Sinphung-ri.

The tunnel is a road that enters a hill and then disappears. The road is connected to a network of roads within a valley with only two entry/exit points, both of which can be blocked off. The valley contains military sites and other facilities that don't match the typical rural surroundings found in this area.

The tunnel road itself is treelined and itself forms a small separate network of paths, distinct from the main roads. While not exclusive to these purposes, treelined roads are a typical feature for military roads and those used by the Kims.

Location of the area's roads, secret tunnel, and the 'north-south road' which eventually merges with another road leading to the Mount Myohyang Palace.

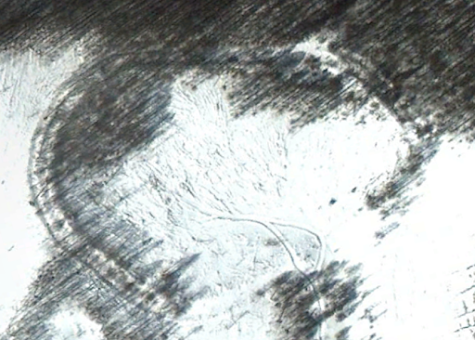

The tunnel doesn't have a clearly defined exit point, but one may exist at 39°52'18.11"N 126°22'52.32"E, which is 0.7 km away. There is an apparent spoils pile indicative of tunneling work, but the available images are not clear enough to make a definitive identification.

There is also no clear evidence of major excavation work using Landsat imagery going back to 1984. However, the small base next to the tunnel did exist in 1984, so either the tunnel was constructed prior to that year - when I don't have imagery - or it was built after but they took care to keep the site very clean, so land disturbances aren't especially obvious in the lower resolution imagery that Landsat provides.

There is a main north-south road in the valley. The tunnel road connects to it and the possible tunnel exit would also connect to the main road. This road runs beneath Neultegi Mountain through a tunnel and continues on until it merges with another north-south road. This second road is protected and eventually goes under Myohyang-san, where it leads to a former mountain palace 12 km away. The tunnel under Myohyang-san was constructed ca. 1993.

The mountain palace was favored by Kim Il Sung and is rumored to be the place where he died. It was eventually demolished by Kim Jong Il.

This entire area, the valley, the treelined tunnel road, the second north-south road, and the area around Myohyang-san (Hyangsan) are all secured and traffic is regulated through the region.

The region's security and the tunnel's connection with this closed-off road network is what makes this tunnel interesting. But unlike the tunnel through Neultegi, which is simply providing an efficient transportation route, the tunnel this post is talking about doesn't provide a better or safer route through the valley. In fact, if it does cut through the hill and exits on the other side, it would make the journey longer. From a strictly transportation viewpoint, the tunnel is pointless.

With all of this in mind, I think that the tunnel is either part of a larger tunnel network for the Kims as I have discussed before, or (particularly if it has an exit) that it could be a kind of emergency safe zone - a place where the Kim's motorcade could hide for a short period of time in the event of conflict or internal crisis until the surface roads became safe again.

Within 15 km of the tunnel are numerous military sites (including the HQ for the KPA IX Corps) and a series of other secured building complexes that are all located behind gates, roadblocks, and dead ends. It's within that wider network that this tunnel is located, and it is this complex interconnectivity that suggests this is no simple tunnel through a hill.

I would like to thank my current Patreon supporters: Amanda O., GreatPoppo, Joel Parish, John Pike, Kbechs87, Russ Johnson, Ryan Little, and ZS.

--Jacob Bogle, 7/23/2022