While the outline of the security fence system remains, the fences and guard towers have all been demolished. As well, during the 2012-2013 time frame, regular domestic buildings were constructed including town administrative buildings, Juche study halls, and monuments. These are items that are largely missing from prison camps but exist in practically every town and village in the country. This strongly suggests that the site has been turned over to civilian use, possibly as a non-penal exile site (as the main roads in and out of the former camp still retain access control points).

The largest changes to the former camp facilities, besides the removal of fencing and guard posts, seems to be the demolition of two buildings within the camp's administrative center, which includes the torture facility.

Camp administrative center in 2010 with buildings of interest.

Camp administrative center with unidentified building and the torture center demolished as of 2018.

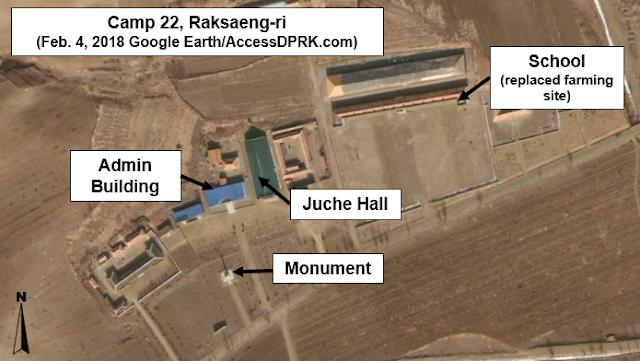

Changes to the villages within the camp attest to its current non-penal nature and shows that something did in fact change in the area's administration after 2012 when all of these changes began to appear.

Raksaeng-ri, a village within the camp as seen in 2011.

Raksaeng-ri after camp closure. Common civilian buildings have been constructed.

The village of Kulsan-ri in 2011.

Kulsan with a new school and other buildings as of 2018.

Agricultural and mining activities appear to have continued with little interruption since the closure as crops can be seen in various stages of growth and harvest over the years, and trains still visit the mining depot. However, the entrance points to the area are still controlled by check points. All of this leads me to believe that the camp is now being used for either one of two things.

The first is that is could now be a regular agricultural and mining area, however, the government still hasn't fully sanitized the former camp of bodies and other evidence that this was a terrible place and so needs greater control over who gets in and out.

The second is that this is a non-penal location used to send exiles and other non-criminal undesirables. The nearby county of Onsong (which also used to have a prison camp) and the northern reaches of the country in general have long been regions to which the government sent exiles. Pyongyang is regularly purged of "lesser" citizens and there are reports of "abnormal" people (like dwarfs) being rounded up and sent to places out of sight of the capital and visitors.

There is a third option but it is unlikely, and that is that the camp is still a prison but is being administered in a radically new way.

The main entrance check point as seen in 2016.

It is an unequivocal positive that there is one less prison in North Korea, however the regime seems to show no real interest in doing away with political prison camps or mass internment in general. Prisons like Chongjin, Kaechon, and Chongori have all been expanded in the last decade and repression continues unabated.

--Jacob Bogle 11/1/18

www.JacobBogle.com

Facebook.com/JacobBogle

Twitter.com/JacobBogle